|

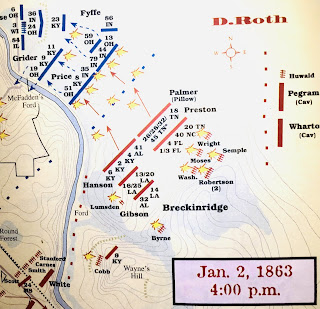

On Dec. 17, 1864, the Battle of the West Harpeth was fought along Columbia Pike,

present-day Route 31. (CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE.)

|

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter

ON DEC. 17, 1864, from

Hollow Tree Gap to the West Harpeth River — roughly 10 miles — the U.S. Army battled the ragtag Army of Tennessee’s rearguard in the aftermath of the Battle of Nashville. "On goes the frightened foe," an Iowa regimental chaplain wrote of John Bell Hood's retreat, "and on follows the victorious pursuer."

|

2nd Iowa Cavalry soldiers, believed to be

from Company M.

(Image courtesy Darrell Van Woert)

|

About six miles south of Franklin, William McCormack — a 37-year-old married father of six from Liberty Township, Iowa — fell in a field that has yet to be swallowed whole by ravenous Middle Tennessee developers. "One of the bravest men I ever saw," an Illinois officer called the 2nd Iowa Cavalry private.

On a deep-blue sky morning, I aim to see where a Confederate bullet ended McCormack's life at the Battle at the West Harpeth — one of those fights that seldom earn more than a few words in a history book. I park at a business/residential development, scramble up a hill and manuever across a small bridge on Columbia Pike — that's Route 31 to those of you who live in the 21st century.

In the far distance to the left stands a tree line in the middle of a field — beyond it is where the Iowans are believed to have advanced. A mile or so to the north appear two ridges bisected by the pike — the U.S. cavalry came rumbling down that road. Steps away, a seldom-visited historical marker explains where Confederates, "moving rapidly south," held off U.S. Army and cavalry. Nearby, the West Harpeth, swollen from a recent storm, seems angry; so do the Columbia Pike/Route 31 speed demons.

Then my mind drifts back to that gloomy day in 1864 ...

GOOGLE STREET VIEW: Present-day view of West Harpeth battlefield.

AT ABOUT 2 P.M, U.S. Army cavalry advances southward on Columbia Pike with bad intentions but no infantry support — Thomas Wood's IV Corps is stalled at the Harpeth River in Franklin, where earlier U.S. Army cavalry

charged a small fort diabolically ringed with telegraph wire.

The 2nd Iowa Cavalry, on the Federals' extreme right, advances near the Nashville & Decatur Railroad tracks. Armed with

seven-shot Spencer repeating rifles capable of firing 14-20 rounds a minute, the Iowans are confident but nervous. "[Our] horses were poor and so much blown that they could only raise a slow trot,"

recalls Major Charles C. Horton, the Iowans' commanding officer.

|

The 2nd Iowa Cavalry, on the Federals'

extreme right flank, advanced near

the Nashville & Decatur Railroad tracks. |

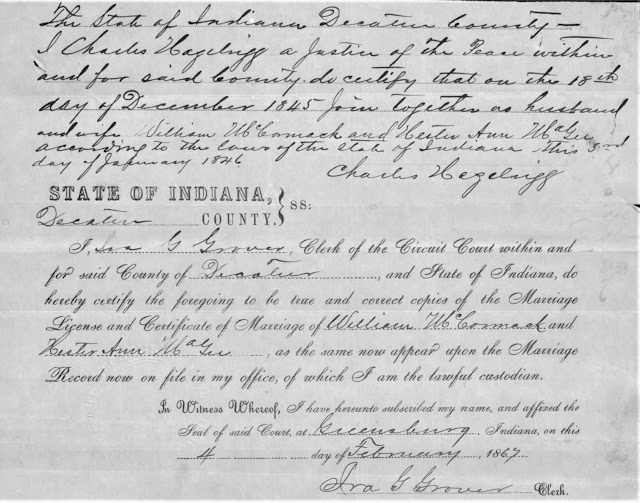

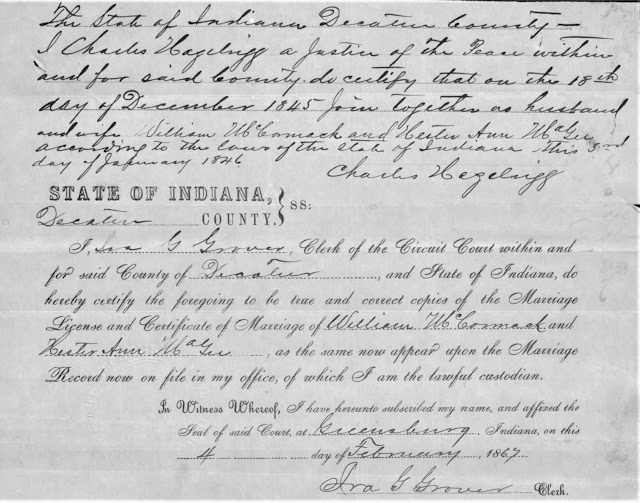

Surely McCormack's thoughts drift to his family in Liberty Township. He has six children: George, 18; Robert, 14; Mary, 12; Henrietta, 8; Anna Bell, 4; and Willie Jane, 1. Somehow wife Esther makes do on their farm without her Kentucky-born husband, who enlisted less than a year earlier. The couple were married in Indiana in 1845.

The Iowans dismount to attack. Then Rebel artillery opens up with grape and canister. Things get ugly quickly.

"We had a long ride over a very rough country before we reached the rebel lines,"

a 2nd Iowa Cavalry soldier recalls. "The Little Harpeth also had to be crossed, which, together with the volleys of the enemy from a strong and well covered position, completely broke our line before we reached them. As we neared the fence behind which the rebels lay, we were greeted by a galling and well aimed fire which carried death to many a noble heart."

Dismounted, well-concealed Confederate cavalry prove difficult to dislodge. After the Iowans struggle past a fence, fierce hand-to-hand combat breaks out. In near-darkness and fog, Union soldiers can hardly tell friend from foe. Enemy attired in blue uniforms make it even more difficult. In a close-quarters brawl, frantic soldiers bash each other with muskets, pistols, and sabers.

"Many of our boys, mistaking the enemy for friends, rode into their lines, and either obeyed the summons to surrender, usually pronounced over a dozen leveled muskets, or by desperate fighting cut their way out with fearful loss,"

the 2nd Iowa Cavalry soldier remembers.

|

1860 U.S. census listed William McCormack as a farmer. The value of his property was

$6,400, above average for the era. |

|

William McCormack married Esther Ann Magee on Dec. 18, 1845.

(McCormack widow's pension file | National Archives via fold3.com | WC106421) |

MULTI-ACT DRAMAS play out all over the field.

Overwhelmed, an Iowan surrenders. Then a shot from a comrade's carbine kills his captor, allowing the man to rejoin the battle — the fiercest fought by the regiment, the Iowan recalled.

Irish-born Dominic Black, a 21-year-old wagoner from Iowa City, orders a Confederate color bearer to surrender. When the soldier refuses, Black rushes the Rebel, intending to slash him with his saber. But a color guard shoots the private through the heart, killing him. Moments later, Sergeant John Coulter —who commands Company K — snatches the flag, then almost instantly gets an enemy bullet through the shoulder. Despite the severe wound, Coulter makes off with the prize.

A Rebel jams the muzzle of his gun into the chest of Private Thomas Wall, who pushes the barrel past his side. Another soldier rushes to Wall's relief with an empty carbine. Then the Confederate instantly whips out a pistol and discharges it at the cavalryman's head, missing him. In a blur, the Iowan snatches another pistol from the Confederate's belt and kills his antagonist.

Moments later, Wall shoots another Rebel who had attacked his comrade. Aiming to escape the madness, he becomes a prisoner. But as Wall walks to the rear, Private Henry Hildebrand rushes to his rescue. He aims a gun toward a Rebel's face and ... click. The weapon fails to discharge. Stunningly, the Confederate's weapon does the same. Private William Magee rushes to Hilderbrand's side, but a Rebel whacks him in the head with his musket. Charles Shultz, an 18-year-old, German-born private, kills Magee's attacker.

Another Rebel fires at

Levi Lewis Backus, a 21-year-old corporal, after the Iowan demands his surrender. Enraged, Backus refuses to take the man prisoner but misses the Reb with a close-range shot. "Damn you, I'll teach you to shoot at me after I have surrendered," the pistol-packing Confederate shouts as he rushes Backus. The cavalryman smashes the Rebel with his Spencer and kills him with a well-aimed bullet. Then Confederate lead crashes into Backus' hand, tearing off two fingers. Nearby, an Iowa private loses an eye in a brawl with a Confederate officer.

Somewhere in the maelstrom, McCormack, of Company B, and three other soldiers struggle to capture a Confederate flag. But each suffers a fatal wound. In all, the Iowans' casualty sheet lists seven killed, eight wounded and 13 captured. The Iowans take 50 prisoners. Within a few yards lay eight dead Rebels— testament to the "desperate nature of the conflict,"

Horton writes.

Confederate counterattacks prove fruitless thanks, in part, to a stubborn defense by the 9th Illinois Cavalry. "I never heard better vollies fired over a grave than these Illinois boys fired that night," the 2nd Iowa Cavalry soldier recalls.

|

| A view of the seldom-visited West Harpeth (Tenn.) battlefield. |

IN THE EVENING, soldiers plunge shovels into Tennessee earth. Someone retrieves money from McCormack's remains before he is lowered into a makeshift grave. No one lingers — there's more fighting ahead.

More than two months later, McCormack's widow receives a three-page letter from Captain John L. Herbert, her husband's commanding officer in Company B. (Letter and transcript below.) The officer discourages travel to Tennessee to recover William's body. "Hardly possible," he writes.

But at least Herbert offers a few comforting words.

"A soldier's grave I think is the most honorable of any, even if in the wilds of India," he writes. "Yet I know it is one of the greatest comforts to have relations or friends (killed in battle) buried in the home churchyard.

"You indeed have lost a noble husband, one that is worthy the love and esteem of every one," the officer adds, "and America has lost one of her bravest sons."

POSTSCRIPT: William McCormack's remains probably were disinterred from the West Harpeth battlefield and re-buried in Franklin. His final resting place, however, is unknown.

|

| (McCormack widow's pension file | National Archives via fold3.com | WC106421) |

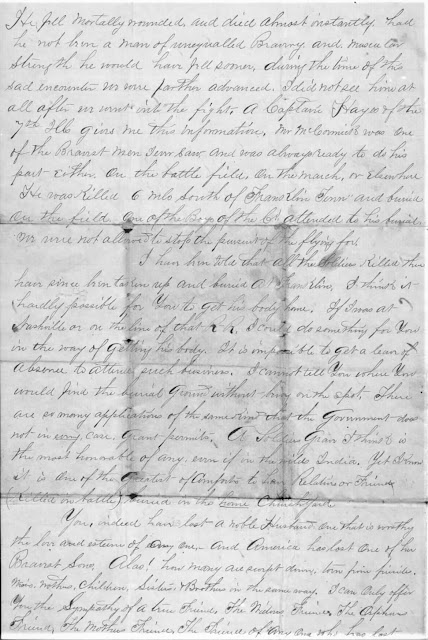

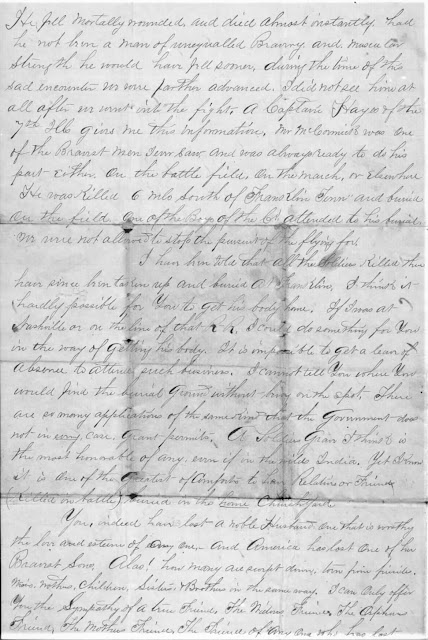

Camp 2nd Iowa CavalryEastport, Miss Feb, 25, 1865Mrs. McCormack

Dear Madam

Yours of the 7th this inst. is just read. I must say that had I thought for an instant that you had not been informed of the particulars of the death of your husband that I would have written you sooner. I had no opportunity for a month after the sad occurrence at which time I was told by boys who had necessary opportunities that the friends and relations of all men killed and wounded were apprized [sic] of it. It is a sorrowful task which is every company commander's duty to perform. I do not wish to harrow up the feelings of an already bleeding heart by a simple repetition of sorrowful facts already known. I will give you the particulars so far as I know.

On the 17th Dec. while drive the retreating foe from Franklin, Tenn. we came suddenly upon a strong line of infantry and artillery, were ordered to charge the position & if possible take the guns. We bring on the right of our line [and] swing clear around on the flank & rear of the Reb battery. Our line in centre was driven back which made a gap on our left. The enemy took advantage and threw a heavy line in the gap immediately in rear of a part of our line. A portion of the regt. had to fight hand to hand to get out. Mr. McCormack was one of the [unreadable] After extricating himself from the first precarious position he necessarily threw himself into another (as they had him almost immediately surrounded). In the next engagement ....

|

|

... he fell mortally wounded and died almost instantly. Had he not been a man of unequalled strength and muscular strength he would have fell sooner. During the time of this sad encounter we were farther advanced. I did not see him at all after we went into the fight. A Capt. [Charles] Hayes of the 7 Ill. gives me this information. "Mr. McCormack was one of the bravest men I ever saw, and was always ready to do his part—either on the battlefield, on the march, or elsewhere." He was killed 6 miles south of Franklin, Tenn. and buried on the field. One of the boys of the Co. attended to his burial. We were not allowed to stop the pursuit of the flying foe.

I have been told that all the soldiers killed then have since been taken up and buried at Franklin. I think it hardly possible for you to get the body home. It is impossible to get a leave of absence to attend such business. I could not tell you where to find the burial ground without being on the spot. There are so many applications of the same kind that the government in every case grant permits. A soldier's grave I think is the most honorable of any, even if in the wilds of India. Yet I know it is one of the greatest comforts to have relations or friends (killed in battle) buried in the home churchyard.

You indeed have lost a noble husband, one that is worthy of the love and esteem of every one, and America has lost one of her bravest sons. Alas! How many are swept down, torn from friends, widows, mothers, children, sisters & brothers in the same way. I can only offer you the sympathy of a true friend, The Widow's Friend, The Orphan's Friend, The Mother's Friend, The Friend of anyone who has lost ...

... a relation or friend while battling for the rights of the true American Citizen.

He had on his person $135 35/100 dollars which Capt. Hayes got and delivered to me. I sent it by R.A. Carleto Paducah, Ky., with orders to express it to you with the necessary information or explanations. He clothes I gave into the possession of R.R. Elder. He said he would send them the first opportunity to you. There is due him 56 56/100 $ back pay and $240 bounty (probably some money for clothing deducted). In addition to this you are entitled to a portion as the widow of Mr. McCormack. You had better apply to some agent who attends to such business. I think some of the lawyers in Marshall perhaps attend to such. The per cent allowed by law is ten percent of money collected and $10.00 for pentions [sic]. His final statements and inventories of effects have been sent. Any other information, or assistance, in my power I will freely and gladly give.

Very respectfully

John L. Herbert

Capt. Co. B., 2nd Iowa Cavalry

— Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES- Burlington Weekly Hawk-Eye, Burlington, Iowa, Dec. 31, 1864.

- Pierce, Lyman B., History of the Second Iowa Cavalry, Burlington, Iowa: Hawkeye Steam Book and Job Printing Establishment, 1865.

- War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1886.

- William McCormack widow's pension file, National Archives & Records Service, Washington, via fold3.com (WC106421).