Then we're off to Richland Creek for a visit to the little-known battlefield where General John Bell Hood's Army of Tennessee fought in the aftermath of its catastrophic, mid-December 1864 defeat at Nashville. The gallant JBH—known by some misguided historians as "Old Woodenhead," which doesn't seem flattering at all—sure mastered retreatin' back in the day.

While cars whiz past us as we stand on a bridge over Richland Creek, Jack gets nervous but somehow finds the courage to read an account of the Christmas Eve 1864 cavalry battle—a fight that involved 6,000 Yankees, 3,000 Rebels and 20 cannon.

No historical sign marks the Richland Creek battleground, and I'm almost positive the occupants of every vehicle that passes us wonder why two old dudes are outside in the cold—it's 27 degrees!—examining a book about Old Woodenhead's retreat. (Watch video.)

|

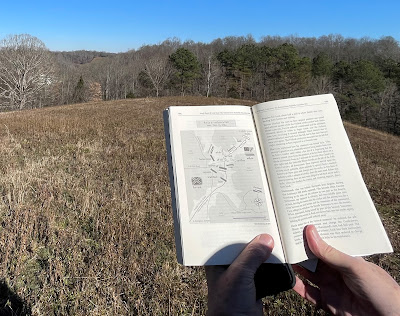

| Richland Creek, where the armies fought on Christmas Eve 1864. |

|

| At Richland Creek, Union cavalry advanced on this ground toward the camera position. |

|

| At the Battle of Richland Creek, Confederate placed artillery somewhere in the left distance. |

As we zoom to Pulaski, birthplace of the Klan, I consume the Big Johnny's burger, worrying if the delicious 1/3-pounder with tomato and the huge onion could cause my demise—and if it does, will Jack return the vehicle to Mrs. B? (Warning to Jack: If she finds a single, solitary gum wrapper left in the car, you will experience a wrath from hell.)

|

| The tiny Sam Davis Memorial Museum. |

Naturally, before we arrive in Pulaski, we pull off to the side of the busy road to read a weathered, state historical marker about some maneuverings by

John Schofield—the U.S. Army general who

flummoxed Hood at Spring Hill in November 1864. This shows we are:

A.) Nuts

B.) Devoid of common sense

C.) Must get out more

D.) All of the above

Few stop at this dangerous spot since the installation of the sign in, like, 1947. (For the historical record, Mrs. B votes for "B.")

On a ridge overlooking Pulaski, within site of the fabulous Giles County Courthouse in the square, we inspect the exterior of the Sam Davis Memorial Museum on the site where the U.S. Army hanged the 21-year-old Confederate spy in 1863. It may be the smallest musuem you'll ever see.

Now I'm not naming names, but someone in our party—perhaps miffed the little place is closed on a Saturday—calls it a "munchkin museum," a description that I don't think appears in any Giles County visitors brochures. Meanwhile, I tap into my inner Mathew Brady for a photo of a large icicle hanging from the side of the architectural wonder.

|

The Giles County Courthouse serves as backdrop for the Sam Davis monument in

the square in Pulaski, Tenn. (CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

|

| A statue of Sam Davis, the "Boy Hero of the Confederacy," in Pulaski's square. |

|

| A close-up of plaque on the Sam Davis monument. |

|

The blank historical marker

on the building where

the KKK was founded

on Christmas Eve 1865. |

After we park at the county courthouse, Jack marches off to check out some historical plaque, leaving me to wander about the square, where I examine the statue of spy Sam Davis—the "Boy Hero of the Confederacy.".

Down the street, around the corner from a psychiatrist's office, stands the building where a small group of Confederate veterans founded the Klan on Christmas Eve 1865. In 1989, the bronze historical marker on its brick exterior was removed, flipped around with the words denoting its KKK association facing the building, and welded back into place. The owners of the building

—an office for attorneys today

—didn't want it to become some weird place of worship for disgraceful Klan supporters.

With time to kill, we head on down the road to check out where Union scouts disguised as Confederates captured Davis while he dozed under a plum tree. You can't make this stuff up. Then we reverse course for the real reason I stole borrowed Mrs' B's vehicle. In journalism school at West Virginia University long ago, I learned this is called "burying the lede."

|

| The view from where Forrest's artillery shelled the U.S. Army at the Battle of Anthony's Hill. |

|

| The bed of a wartime road on the Anthony's Hill battlefield. |

On this deep-blue sky afternoon a few miles south of Pulaski, we meet John Nelson, the no-B.S. owner of a core section of the Anthony's Hill battlefield. After confirming our Civil War bonafides, the 83-year-old descendant of slaves shows us about his wooded, hilly property. Every time he walks the ground, owned by his family since 1869, Nelson thinks about the sacrifices his ancestors made to maintain it. Many of his kin rest in a cemetery across the road.

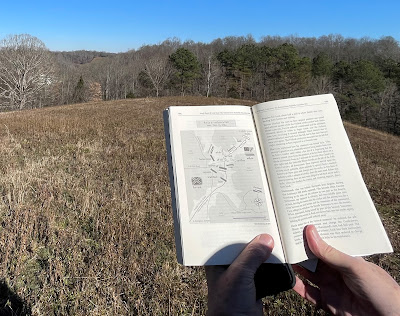

|

Using an Anthony's Hill map from Mud, Blood & Cold Steel

by Mark Zimmerman, Jack Richards and I explored

the little-known battlefield near Pulaski, Tenn. |

At Anthony's Hill on Christmas Day 1864, Nathan Bedford Forrest

—the

notorious slave trader and cavalry genius

—ambushed Union soldiers under Major General James Wilson. The weather was bleak, with rain mixed with snow, and freezing temperatures.

Nearly continous fighting for more than a week had left both sides exhausted. Many of the Rebels went shoeless. Casualties numbered roughly 200 on both sides combined. A mortal wound took Christian Brenner, a private in the 5th Iowa Cavalry, from his wife Sarah Jane and their only child, 5-year-old Mary Charity.

Behind his house, near a coop of clucking chickens, Nelson points out ground where Forrest deployed artillery to shell the U.S. Army. To take in the magnificent view of the valley below, I crawl underneath barbed wire with the aid of another tramper. With a battlefield map in hand, Jack joins me.

Later, Nelson points out other landmarks—the wartime roadbed that slices through the heart of this hallowed ground, the site of the church used by Forrest as a hospital, the cemetery where Confederate dead from the battle rest. Instincts tell me there is a great story to tell about Nelson, Forrest and this long-forgotten battlefield.

Until then, we'll see you down the road. As always, let's keep history alive.👊👊

|

| Grave of a Confederate soldier who fell at Anthony's Hill. |

— Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.