|

| My journey started in Lynnville, Tennessee, the town that suffered a "partial burning" by the Union Army, according to this historical sign. |

Like this blog on Facebook | My YouTube videos

|

| Great fried pies are sold here in Lynnville. |

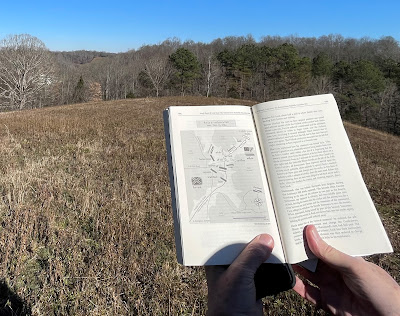

My first stop after departing Lynnville — which suffered a “partial burning” by the United States Army during the war, per a historical marker in town — is the Richland Creek battlefield. Here, on Christmas Eve 1864, the outnumbered and ragtag rearguard of Hood’s army fought against United States cavalry. As I have a half-dozen times, I park near the modern bridge over Richland Creek and try to imagine the fighting.

Somewhere out here, perhaps on Milky Way Farm across the Pulaski Pike, Nathan Bedford Forrest — Rebel cavalry genius, “The Wizard Of The Saddle” and postwar Klansman — directed troops. And somewhere out here, an obsessed Union cavalryman named Harrison Collins captured the object of his longtime desire — a Rebel flag — by stooping down and picking it up. For his bravery, he earned a Medal of Honor.

|

| Unheralded Richland Creek battlefield. |

“Your shop sure smells good,” I tell the three delightful women behind the counter. No battlefield tour results, but I enjoy a brief staredown with a strange-looking cat who smiles at me from covers of a half-dozen Dr. Seuss books on the gift shop shelves.

On my return to the pike, I flag down a local in a pickup truck, but the conversation goes like one you might have underwater with a friend. All the time I am thinking to myself: “DON’T YOU KNOW HARRISON COLLINS EARNED A MEDAL OF HONOR OUT HERE!”

Sigh. The life of a Civil War obsessive.

After that respectful convo, I travel south past Pulaski, where ex-Rebel soldiers founded the evil Klan on Christmas Eve 1865, and toward the Alabama border (gulp) for a visit to the Anthony’s Hill battlefield, where “The Wizard” fought off U.S. cavalry on Christmas Day 1864.

Before the battlefield stop, I visit a place my dad (“Big Johnny”) and momma (“Sweet Peggy”) — RIP to both ❤️❤️ — would have loved: a combo antiques store/AJ’s One Stop Deer Processing. An antler cap cut here will set you back 10 bucks, extra sausage is a cool 30 large.

|

| Mom and Dad would have appreciated this place. |

Inside I enjoy the smell of deer carcasses — pssst! it’s not like those wallets in Lynnville — and admire a multitude of deer heads hanging from the wall and a 1964 “Sport” magazine with Sandy Koufax, a hero of mine, on the cover.

|

| Confederate dead from Battle of Anthony's Hill. |

In a flash, I’m zipping south on the pike, destination Sugar Creek — the final battle of the Nashville Campaign. I hope to put my drone in the air for a view of the battlefield, where only a few dozen fell on Dec. 26, 1864. But remember: Somewhere a momma and poppa mourned their deaths just the same.

Unfortunately, I don’t find a launch point, but I do find a general store (closed), where according to a source, Sugar Creek battlefield relics sit. Nearby, behind a barbed wire fence, a brown and white horse walks my way.

“What does he know about the Battle of Sugar Creek?” I wonder. But alas, I must go. Sadly, a return to the 21st century awaits.