|

A musket ball found at the site of Lunette Negley in Murfreesboro, Tenn.

(CLICK ON ALL IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

PANORAMA: Developers have claimed the site of Lunette Negley.

(Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter

On a brisk, windy afternoon, the 21st century batters the 19th in another unequal fight in Murfreesboro, Tenn.

Bulldozers and other earth movers grunt as they carve up and pound ground on the site of Lunette Negley at Fortress Rosecrans, the largest earthen fort of the Civil War. Near the construction zone, traffic whooshes by on a busy four-lane road. In the distance, a huge crane hovers next to the skeletal frame of a high-rise.

Meanwhile, armed with metal detectors, history buffs Stan Hutson and David Jones aim to recover pieces of the past before the Civil War site is lost forever. Wearing a gray hoodie, blue jeans and work boots, Hutson sweeps his machine across the mostly barren ground. Clad in a light blue, long-sleeve shirt and camouflage pants, Jones pokes at the soil with a shovel. Twenty or so yards away, a mound of earth is all that remains of Lunette Negley’s once-imposing walls.

This isn’t the friends’ first relic hunt here. At the remains of a war-time fire pit, Hutson has found pieces of a mangled U.S. Federal cartridge box plate, a dozen Yankee eagle buttons, shards of period glass from an 1860 Drakes Plantation X Bitters bottle – even cow bones and hog tusks. Elsewhere on the well-hunted site, they have discovered Williams cleaner bullets, a Schenkl artillery shell fragment, a period watch cap, a bayonet, a butt plate to Enfield musket, and a piece of a harmonica, among other artifacts.

“If we don’t save it, it’s gone,” Hutson says of the finds.

|

| Stan Hutson (left) and David Jones hunting the former site of Lunette Negley. |

|

| All that remains of one of Lunette Negley's once-imposing walls. |

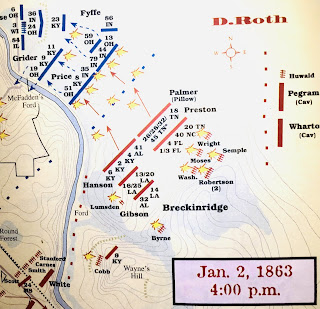

Spurred by William Rosecrans, the Union Army began building the fort in the aftermath of the Battle of Stones River, fought near Murfreesboro Dec. 31, 1862-Jan. 2, 1863. The 42-year-old general considered the site ideal for stockpiling supplies for campaigns or as a strong fallback position in case the Federals were forced to retreat.

Fortress Rosecrans included eight lunettes, four redoubts, steam-powered sawmills, quartermaster depots, warehouses, magazines, and quarters for thousands of soldiers. Its 10- to 15-foot earthen walls were fronted by a 10-foot ditch filled with sharpened stakes. The Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad line ran through the fort, which fed a ravenous Union Army war machine for its advances on Chattanooga in 1863, on Atlanta in 1864, and for William Sherman’s March to the Sea.

“Truly astounding,” wrote a contemporary observer about the skill and labor used to build Fortress Rosecrans. Among the thousands of construction workers who created the marvel were contrabands and soldiers in the Pioneer Brigade, an elite Michigan unit.

“Astonishing,”

The National Tribune, a newspaper for Civil War veterans, called the fort in 1906, “… equal in magnitude and strength to those which defend great cities in Europe.”

In mushrooming Murfreesboro, where developers have wiped out hundreds of acres of Stones River battlefield outside the national park, the National Park Service protects only small slivers of what remains of Fortress Rosecrans.

The fort was abandoned soon after war; in recent years, the Lunette Negley site was a city dump, says Jones, a lifelong area resident. In 2019, the City of Murfreesboro opened a new fire department on the grounds. Across Medical City Parkway, a strip mall opened.

And now, sadly, we witness the

coup de grace of what little remains.

|

| A piece of a hoe discovered eight inches below the surface. |

|

| Brick from a fire pit. |

|

| Trigger guard, perhaps for an Austrian Lorenz musket like the one below. |

“

Beep, beep, beep … beeeeeep, beeeeeep!”

Minutes into his relic hunt, the sound from Hutson’s Fisher F75 detector changes tone, an indication of metal in the deep-brown earth. He scoops out about two inches of soil with his shovel, reaches down, and picks up an unusually shaped object roughly 6 ½ inches long.

|

At the Murfreesboro, Tenn., construction site.

relic hunter Stan Hutson found a trigger guard

for a musket, perhaps part of

an Austrian Lorenz (above). |

“I cannot believe this. Holy cow!” Hutson says. Minutes later, he’s still on a relic hunter high: “I’m gonna get cotton mouth.”

The 19th century has finally let go of a trigger guard for a musket, perhaps an Austrian Lorenz, used by soldiers on both sides in the Western Theater. Maybe the weapon belonged to a soldier who served under 75th Illinois Captain David M. Roberts, who commanded a battery at Lunette Negley. The officer’s artillery included two 6-pounders, a 3-inch gun, a 6-pounder James rifle field gun, and an 8-inch siege howitzer. With such impressive weaponry, the imposing fort was never seriously threatened by the enemy.

A close examination of the ground reveals an interesting mosaic: soil, stone, shards of opaque glass, period nails, and small porcelain chips from dishes. Some, if not all those artifacts, are from the Civil War era.

|

| At the Lunette Negley fire pit site, Stan Hutson holds a large hook, perhaps used for cooking by soldiers. |

|

| A chunk of earth shows evidence of its use as a fire pit. |

Less than a year ago, Jones found on the site a .54-caliber bullet mold, probably Confederate. “It's like Christmas every time I dig,” he says. “You don’t know what you’re going to get when you dig it up.” The day before the Battle of Stones River, Johnny Rebs camped on the ground before their assault on the Round Forest. Nearby, Lt. General Leonidas Polk, a Confederate corps commander, made his headquarters in the James house, which was destroyed by arson in 2003.

|

| A porcelain button found on the surface. |

Probing at the ground after a hit on his metal detector, Hutson uncovers another piece of metal. “What do you think this is?” he asks Jones. “A door handle?” He tosses it on a mound of dirt pushed aside by the construction crew. On the surface, Jones picks up a porcelain button, probably from a soldier’s blouse. Later, he uncovers a .69-caliber round ball.

At the remains of the fire pit, Hutson points out tell-tale burn marks in the soil from a log as well as ash. He finds a large, iron hook and speculates it was used by soldiers to hold a pot for cooking. Scattered about are 19th-century nails, bolts and bricks. He uncovers a piece of glass. “That probably hasn’t seen the light of day in 157 years,” he says, marveling at the mundane piece of history. Fifteen minutes later, he uncovers a piece of a hoe eight inches deep.

About an hour before dusk, diggers’ shadows dance on a bank of soil richly illuminated by the sun. Another relic hunt is nearly over. Time is rapidly running out, too, for another Civil War site in Murfreesboro, Tenn.

|

| Shadow play: A journalist and a digger go about their work. |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES

--

The National Tribune, July 12, 1906.

--

The Summit County Beacon, Akron, Ohio, Oct. 15, 1863.