|

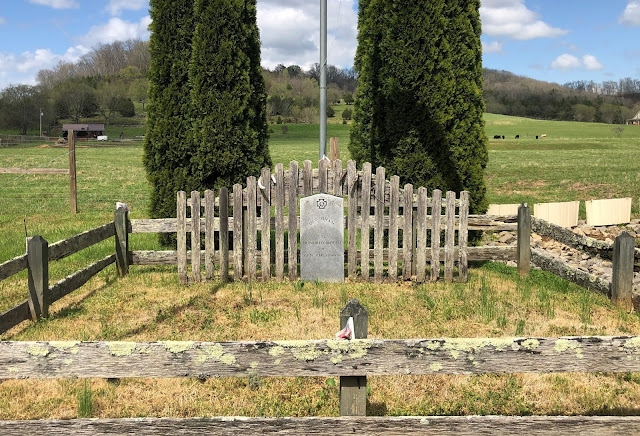

The grave of Old Isham, Confederate General Frank Cheatham's horse.

(Cheatham photo: Library of Congress) |

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on TwitterWARNING! This post includes horse puns that may make you wince ... or worse. Some dialogue may be fabricated. Kernels of history, however, are included.

Confession: I recently became obsessed with the ties between Civil War horses and their riders.

“So stop horsin’ around then,” my wife told me, evidently reading my mind. “I don’t want to be a nag, but you really need to get out of the house, drive into the middle of nowhere, and visit the grave of Old Isham, the wartime horse of Frank Cheatham, the hard-drinking Confederate general who was no friend of the incompetent Braxton Bragg. Besides, I have a friend coming over.”

|

Your tour guide at the grave of Old Isham in

rural Coffee County, Tenn. |

Stunned by my wife’s Civil War knowledge, I took her up on the

suggestion demand. So I trotted to my 2015 Altima — the one with the below-par horsepower — for a ride to rural Coffee County, about an hour from Nashville. "What an idea!" I said with a smile. "Thanks, Mrs. B, you’re no nag at all."

Feeling my oats, I reached speeds as high as 55 mph on Interstate 24 East, zooming past the exit for Stones River battlefield in overdeveloped Murfreesboro and three or four or 25 Cracker Barrel restaurants. At the Beechgrove/Bell Buckle exit, I debated whether to go left or right.

Go right and I could visit the area where British military observer Sir Arthur Freemantle witnessed the worst of America in 1863: a speech by an Arkansas politician at the Grand Review of the Army of Tennessee.

The mouthy pol had a "vulgar appearance," wrote the Brit, and delivered a "long and uninteresting political oration, and ended by announcing himself as a candidate for re-election. This speech seemed to me (and to others) particularly ill-timed, out of place, and ridiculous, addressed as it was to soldiers in front of the enemy. But this was one of the results of universal suffrage."

My other alternative with a right turn was a visit to Bell Buckle, hometown of former Hee Haw star Molly Bee and the Moon Pie Capital of Tennessee. Bleh, moon pies always give me a stomach ache.

|

A horseshoe on a fence near

Old Isham's grave. |

But I lean left, so that's the direction I headed ...and promptly got lost. Then I got angry when a guy tailgated me on a two-lane road. “Get off your high horse!” I screamed, eyes fixed straight ahead, arms firmly gripping the steering wheel, and all my windows rolled up.

Sweating profusely, I zigzagged through unfamiliar territory. (By the way, I didn’t spot one Starbucks in Coffee County. Weird.) Finally, I came to a “T” and correctly made a right on French Brantley Road, slowly driving past a small general store and a pig farm.

By the side of a lonely country road — aren’t they all? — I at last found the grave of Old Isham, who died in 1884, age 23 or 24. Master Frank died two years later, age 65. What a great place for a horse to rest for eternity: a gorgeous valley, swaths of green, a mansion atop a hill in the distance, and a few cows, some eyeing me warily. It was only marred by the name of the place: Starr Trek Farm. Ugh, I hate William Shatner commercials.

Old Isham’s neatly tended grave was bordered by a modest, wood fence adorned with small Confederate flags. Probably placed there by colt followers. (Sorry.) On a fence behind the grave marker, someone placed a horseshoe, a neat touch. I shot a panorama, took the requisite selfies, and silently thanked my wife for the spur-of-the-moment idea.

|

| A bronze statue of Roderick, the favorite horse of Nathan Bedford Forrest. |

Suitably inspired, I hoofed it over to Thompson's Station days later to check out the statue honoring Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s favorite mount, Roderick. (True story: At the H Clark Distillery in Thompson's Station, the experience manager told me that cows love their bourbon mash. “They come running for it," she said. "Then they just lay in the field, chilling.”

Neigggh, you say? Hey, it's on my blog

right here.)

At the

Battle of Thompson’s Station (Tenn.) on March 5, 1863, Roderick was wounded three times before he was guided to safety by the general’s 17-year-old son. Eager to return to the "Wizard of the Saddle," however, the chestnut gelding leaped over several fences, suffering a fatal bullet wound in the process. Forrest -- the notorious slave trader/cavalry genius -- supposedly wept beside the dying animal, who was buried on the battlefield.

If not for the roar of the crazy traffic on Columbia Pike (State Rt. 31), construction equipment, convenience store, and other modern development/schlock, heck, you're back in 1863 in Thompson's Station. I know that might, ahem, stirrup trouble with the pro-development crowd.

The bronze statue of Roderick stands roughly 200 yards from the circa-1820 Spencer Buford Mansion on Columbia Pike. The place has some very weird modern additions that ruined its historic integrity and forced its removal from the National Register of Historic Places. Sort of like sticking McDonald's hamburger wrappers on a work of art.

Roderick’s remains may rest today somewhere near the statue, perhaps where an upscale development named after the horse will be built. I imagine that could provide fodder for future conversations: "Honey, the workers were digging in our flower garden, and they found this huge skull.”

"What?"

Ok, enough schtick. Let's keep history alive.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

SOURCE:

-- Freemantle, Arthur James Lyon, Three Months In The Southern States: April-June, 1863, Published by John Bradburn, New York, 1864.