|

| Stan Hutson holds his tintype of Julius Waite near the site of the Union soldier's death. |

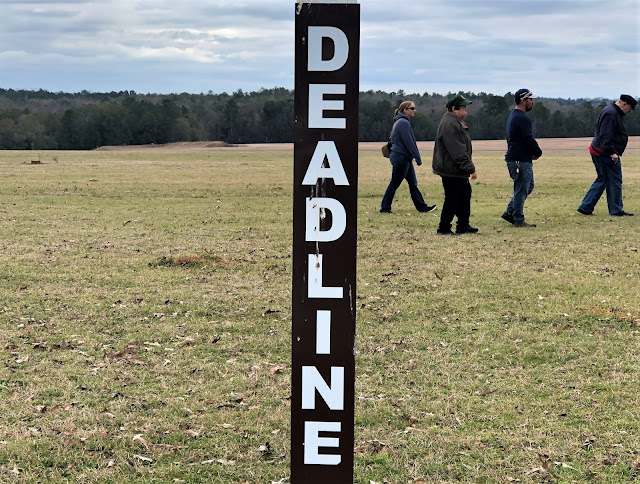

In 2019, Alabama native Stan Hutson — who cares deeply about the battlefield — took me to key points on the field. (Read my Civil War Times column.) We examined ground where soldiers paid the ultimate price outside what today is the national park, which encompasses only a fraction of the battlefield.

Here are the sites where five Battle of Stones River soldiers were either killed or mortally wounded on Dec. 31, 1862.

While leading his men at roughly 9 a.m. on December 31, 1862, Union Brig. General Joshua Sill was killed in the area above by a bullet that struck him in the face, penetrating his brain. The 31-year-old commander died wearing General Phil Sheridan’s jacket, mistakenly picked up by Sill during a military conference earlier that day. The men, good friends, had roomed together at West Point.

While leading his men at roughly 9 a.m. on December 31, 1862, Union Brig. General Joshua Sill was killed in the area above by a bullet that struck him in the face, penetrating his brain. The 31-year-old commander died wearing General Phil Sheridan’s jacket, mistakenly picked up by Sill during a military conference earlier that day. The men, good friends, had roomed together at West Point.

“No man in the entire army, I believe, was so much admired, respected, and beloved by inferiors as well as superiors in rank as was General Sill," a Union officer said afterward.

Sill’s death site is unmarked, forgotten, in the midst of retail businesses.

Sill’s death site is unmarked, forgotten, in the midst of retail businesses.

|

| Somewhere out there in the sprawl of Murfreesboro, Tenn., John Penland was mortally wounded. |

In or near Hell’s Half-Acre, John Penland, a 45-year-old private in the 57th Indiana, suffered a severe wounded when a cannon ball grazed across his stomach. After examining his map, Hutson figured the married father of nine children was shot near the busy road in the near distance, “between the Dollar General Store and that Gerber’s sign.”

Penland, who had three sons in the Union Army, held in his intestines and walked a mile to his camp. He died from infection and fever on Jan. 4, 1863. Here's more on Penland on Find A Grave.

(Image courtesy Richard Penland)

Even at the doorstep of the national park, nearly within site of the heart of the Slaughter Pen, the 21st century leans creeps closer into the 19th. Until 2017, this land upon which Mississippians, Tennesseans and Alabamians advanced on Dec. 31, 1862, was mostly open field, dotted with old-growth trees and a few houses.

(Image courtesy Richard Penland)

Even at the doorstep of the national park, nearly within site of the heart of the Slaughter Pen, the 21st century leans creeps closer into the 19th. Until 2017, this land upon which Mississippians, Tennesseans and Alabamians advanced on Dec. 31, 1862, was mostly open field, dotted with old-growth trees and a few houses.

In the attack, James Lockhart Autry, a lieutenant colonel in the 27th Mississippi, was killed by a bullet to the head. The 31-year-old lawyer and politician from Holly Springs, Miss., left a wife named Jeannie and a 3-year-old son, James II. Now the area where Autry was killed is occupied by a 116-bed hospital and a parking lot. Here's more on Autry on the Rice University web site.

Autry photo: “Col. James Lockhart Autry,” Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, accessed December 29, 2019.

Abner Columbus Ball, a private in Company G of the 22nd Alabama, was killed the day after his 35th birthday. He left behind a wife named Nancy and four children – two boys and two girls. The farmer was buried on the battlefield; his remains were recovered and re-buried in Murfreesboro’s Evergreen Cemetery, where many Confederate dead of Stones River rest.

Autry photo: “Col. James Lockhart Autry,” Woodson Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, accessed December 29, 2019.

|

| Suburbia has claimed the area where 22nd Alabama Private Abner Ball was killed. |

Did Ball die by what’s now a tire store? Was he originally buried by the present-day gas pumps at the convenience store? Hutson and I stood in the approximate area where Ball died. But because the ground bears no resemblance to the 1862 scene, there's no way to be sure.

(Abner Ball photo courtesy Stephen Cone)

Julius Berdan Waite, a 30-year-old private in Battery E of the 1st Ohio Light artillery, was killed in the opening action of the battle. Hutson owns a tintype of the soldier — "probably an image he sent to his wife,” he told me.

(Abner Ball photo courtesy Stephen Cone)

|

| Julius Waite was killed near what today is a parking lot for a dental clinic. |

In a Napoleonic pose, a bushy-bearded Waite, a farmhand as a civilian, stares straight ahead, the thumb of his large hand tucked inside his military jacket. The area where Waite was killed is near busy, five-lane Old Fort Parkway, a dental clinic, convenience store and an apartment complex construction site. About 15 years ago, the area was largely open fields.

(Waite image courtesy Stan Hutson)

(Waite image courtesy Stan Hutson)