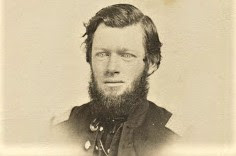

Under the headline "Taps Sound for Corp. Patterson," a front-page obituary in

on Sept. 30, 1916, briefly recounted the last days of a Civil War veteran. What a wartime experience he had.

In poor health the previous five months, Robert Patterson — “Corporal Bob,” as he was commonly known — visited the newspaper office on a Friday morning, then checked on a fellow veteran. Later that evening, the 74-year-old pension attorney attended a theater performance with his wife. As they neared their home afterward, Patterson felt weak. He sat down in the house, then stood up and keeled over, dead. Cause of death: Old age and Bright’s disease.

“A grand old gentleman,” the newspaper called Patterson, who fought in more than a dozen major battles — including Gettysburg, where he was wounded and briefly a captive.

“His position as pension attorney was the joy and the ‘all’ of his life,” the

Morning Star reported, “and it is by old soldiers and widows that he will be missed most of all. He was a man with great charitable ambitions and spent both his time and money in the helping of those who had fought beside him in the great civil strife.”

The obituary wasn’t the first one written about the man who somehow survived the Civil War.

At the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, 1862, the 20-year-old private in the 19th Indiana was concussed by an artillery shell burst that sent him and fence rails skyward. Over the next 24 hours, the Iron Brigade soldier witnessed harrowing scenes.

At a battlefield aid station, Patterson watched blood ooze from the chest wound of a fellow private in the 19th Indiana. The man remarkably lived. As Patterson struggled to return to his regiment, he drank “black water” from a stump and became ill. At a makeshift hospital the day after the battle, he saw surgeons amputate limbs, which were buried in a nearby trench. Next to him, a New York soldier writhed in agony from an artillery wound that had torn apart his lower jaw. He begged to be shot.

In a barn in nearby Keedysville, Md., Patterson saw 19th Indiana

Private Joshua Jones’ leg wound covered with maggots. Surgeons were fearful he would not survive amputation, but they performed the operation anyway. Their initial prognosis was correct: Jones died 11 days after the battle.

Weak and exhausted, Patterson slowly made his way back to the 19th Indiana, camped near the Potomac River. Believing he was dead, comrades seemed stunned to see him. His captain was especially astonished: He was writing a note to Patterson’s mother about his death.

“It was the first and only time I have ever read my own obituary,” Patterson wrote in a searing account of his Antietam experience for the Muncie newspaper on the 50th anniversary of the battle, “and I sincerely hope that I will so live out of my remaining earthly life as soldier and citizen that my final obituary may contain as much good as the first.”

Patterson, who was seriously injured in a train accident later in the war, was rocked by tragedy in 1864. His 48-year-old father Samuel, a private in the 36th Indiana, died in an Indiana hospital on Sept. 24, 1864, of wounds suffered at Kennesaw Mountain, Ga.

After the war,

Patterson worked a series of jobs — clerk in the state legislature, postal clerk, postmaster, custodian of the county courthouse and, finally, pension attorney. He also dabbled as an inventor, obtaining patents for a

unique fastener for a fruit jar and a steel-wire curry comb. Patterson also enjoyed writing, becoming the “poet laureate of the Indiana Grand Army of the Republic.” He “delighted in the work,” the Muncie newspaper noted.

On Sept. 18, 1912,

The Muncie Morning Star published

Patterson’s lengthy account of the Battle of Antietam — posted in full below.

“Most momentous scenes,” he wrote.

Surely an understatement.

Scenes and incidents of all the battlefield must be guaged [sic] from the standpoint of individual observation. Commanding generals and through the many grades of rank down to the private in the ranks have a corresponding larger or smaller scope of vision, and the scenes are ever changing as those of the kaleidoscope. All were actors on the stage of the great drama of war in their own role, while civilian spectators and non-combatants were far in the rear and behind anything that afford protection from bodily harm.

I had marched and fought in the ranks of the

Ninteenth Indiana. Infantry, from

Lewensville to Fredericksburg, Va., and from the Rappahannock river back through the series of battles resulting in the second defeat on the historic battle-ground of Bull Run [and] on the first invasion of the Confederate army into Maryland where the first great clash came at South Mountain, September 14, 1862. After terrific slaughter on both sides I had seen the army of invasion driven from their great Gibraltar of natural defense, and under cover of darkness begin its retreat downward on its southern slopes toward the Potomac river, where it made its last stand that resulted in ignominious defeat in the struggle known to the world as the battle of Antietam. Hence my personal observations of the scene must be given from the narrow standpoint of a private who can only see things with which he comes in immediate contact.

We had cared for our dead and wounded at South Mountain on the 15th, when our woefully thin and dust-brown ranks started in persuit [sic] of the retreating army of [Robert E.] Lee, and we were halted on the banks of Antietam creek, where the action of our regiment commenced, and my story begins.

On the afternoon of September 16 we witnessed some of the opening shots of this battle being fired across the creek at the Confederates by Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, of our Brigade, and other field pieces. As the autumn sun was sinking like a great ball of blood that seemed as an omen of events to come, our brigade crossed the creek, and in battle lines moved cautiously forward. In passing where the enemy had killed some cattle, some of our boys had detached strips of fat from the intestines of the animals which they applied to their guns to prevent rust. I had unconsciously raised the hammer of my gun as was applying the grease about the tube as the regiment halted, when I rested the muzzle of the gun against my left shoulder, and in drawing the string of fat through the guard the gun was discharged, the ball passing through the rim of my hat. The explosion was deafening, and many thought I was injured by a bursted shell of the enemy. I have often wondered if that was not the first shot from a musket in that battle, and if it had happened to have killed me would some think it deliberate suicide. However, the Johnnies had so far proved to be poor marksmen in selecting me for a target, and I had rather a hundred would shoot at me than to take a shot at myself.

Our battle lines pressed steadily until darkness precluded further advance without danger of bringing premature engagement. Here we were ordered to "rest on arms." I shall never forget that William N. Jackson (Uncle Billy) lay side by side on our bed of earth with our knapsacks for a pillow, upon that portentious [sic] night. He was one of twelve recruits who had joined our company at Upton Hill on September 7, and the only one of that number who was not killed, wounded or missing in the valley of death at South Mountain just seven days after joining our ranks.

Opening of the battle

PANORAMA: Joseph Poffenberger's farm, where 19th Indiana camped before Antietam.

(Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

|

4th U.S. Artillery Battery B, positioned in a field along Hagerstown Pike, fired "death

into the ranks of gray," Robert Patterson recalled.

(CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE)

|

The very earliest dawn of the morning of September 17th brought a rain of solid shot upon our sleeping ranks from rebel batteries that were stationed during the night within range of our regiment and brigade, Amongst the terrible effects of this firing was the blowing up a casson [sic] of shells and the killing of seven horses of a battery near our lines. It was a sudden awakening from only a short restless slumber to a full realization of our danger from masked batteries supported by infantry who had thrown up breast works during the night for their protection against contemplated attack by our forces. Our lines rose seemingly as one man, and were moved on the double quick time to cover in a piece of woodland, where we were brought to a front facing an orchard enclosed by a fence.

Terrific cannonading was now heard to the right and left, while Battery B and other artillery was hurling death into the ranks of gray. Soon an officer from the staff of General [John] Gibbon, commanding the brigade, dashed up and gave the command to advance to the summit of the hill beyond the orchard.

Lieutenant Alois O. Bachman, who was a graduate from a military school, had commanded our regiment through the previous campaigns, then pushed himself through our ranks, and drawing his sword, his deep bass voice rang out, "Boys, the command is no longer forward, but now it is follow me." I shall never forget following his young, tall athletic form as he ascended the slopes of the hill until he fell dead, his body pierced by minnie balls shot by the columns of the enemy who lay in mass beyond the brow of the hill.

In trying to climb a second fence, a shell bursted apparently just beneath me hurling me with a mass of broken rails high in the air. The concussion injuries were so paralyzing that all seemed a blank to me for some time, I know not how long. On regaining consciousness I found I could not move my right hand or foot, indicating partial paralysis of the right side from concussion of injury of both. Anyhow, I was afterwards placed on a stretcher and placed in the shade, my head against the brick walls of this farm house with other wounded, some worse than myself.

|

Decades after the battle, William Tipton shot this image of a section of bullet-riddled fence at Antietam, perhaps much like the one Robert Patterson was climbing when he was

stunned by an artillery burst. | (History of the 124th Pennsylvania Volunteers 1862-63) |

A boy about my age on my left was moaning piteously and I thought myself lucky when I saw the blood oozing from a bullet wound in his breast with every breath. I tried to encourage him, and when he turned his pallid face toward me I saw he was

Andrew Ribble of Company K of our regiment. He could only wisper [sic], "O, Bob, I'll soon be gone." But he lived to get home, and I learn he was accidently killed by the cars while in the employ of the Big Four railway. I thought at that time he could live but a few moments.

|

"A few solid shots passed

through the brick walls of the

house, throwing particles of brick

and mortar upon the wounded ...,"

Robert Patterson recalled. |

A few solid shots passed through the brick walls of the house, throwing particles of brick and mortar upon the wounded as they were being conveyed to more distant points from the battle scenes. While starting back with me, one of the bearers received a shot in his hand, and I was dropped to the ground near what I hoped was a spring house so common in Maryland, as I was suffering from thirst. With my left hand and foot I drew myself over the sill of the door, and instead of finding a flooring near the surface, my maimed body shot downward several feet, striking upon a bed of sawdust. A standing ladder broke my fall and I was more frightened than hurt. It was an ice house.

Many of the wounded stopped at this door, hunting for water. Two Zouaves of the 14th Brooklyn also stopped, and the larger one placed his head against the cheek of the door and was about to step down, as he could not see in the darkened depths. I yelled, and he asked if I was in a well. Informing him it was an ice house, he descended the ladder and with a bayonet began digging up the ice, handing me a piece and throwing some up to his comrade. The ice was very refreshing to me. Fearing the building might be burned from the fuse of bursting shells, I asked my comrade to help me to the surface, when he put me under the arm of his wounded hand and reached the top of the ladder, where I was drawn out by the comrade above. Starting to carry me away, they reached an open field where the cannon and minnie balls came so thick and fast that I asked them to lay me behind a walnut stump, and they disappeared. I saw a black quantity of water in the hollow of the stump, and being almost crazed with thirst I drank of it from my hand and crawled to a fence surrounding a woods pasture.

|

19th Indiana marker along Hagerstown Pike notes commander Alois O. Bachman "fell mortally wounded

150 yards due East" and regiment suffered 11 killed and 58 wounded. |

|

After 19th Indiana Private Robert Patterson was wounded, he was taken to a nearby

farmhouse -- perhaps David R. Miller's -- where he briefly rested. |

PANORAMA: David R. Miller farm, where Union wounded received care.

(Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

Tearing away a part of a rotten rail, I crawled through the fence and layed down under an oak tree, for I was now very sick, probably caused by the stump water and tadpoles I had drank, and the reaction taking place from my injuries and partial paralysis. But nature asserted itself by ridding my stomach of its vile contents, and I became easier, but with prickly sensations in my right side, indicating returning circulation. I noticed that the sheep in the woods were much frightened at the screeching and bursting shells, and kept running about, while the hogs kept rooting about unless a limb from the trees dropped amongst them.

While laying with my head on the root of this tree a rebel officer mounted on a fine bay horse rode to the brow of a hill in my front, and began to scan the field through his field glasses. This was my first correct idea of the direction of the rebel lines. Fearing he would see and capture me, as I was unarmed, I got up and stood behind a tree. Soon horse and rider dashed in my direction, as I feared to take me prisoner, but he stopped at a tree near the one behind which I stood, and I could have touched the head of his horse while he again looked through his glasses. To my relief, he dashed back and disappeared beyond the hill.

Here I noticed a company of sharpshooters from Pennsylvania deployed as skirmishers advancing across the field from [the] opposite direction. To me they were a gladdening sight, as I understood the notes of command given through the bugle. I pulled myself upon the fence and waved my hat in token of friendship. Their bugle sounded "lay down." When assured I was not an enemy a man was sent to me when he learned of the action of the Confederate major. Learning the direction he went, the skirmisher started double quick down the opposite fence, followed by me, as I could now walk supported by a stick for a cane. I saw him lay his heavy globe-sighted rifle on a fence and fire, In a moment this same horse came dashing back over the hill, without the rider. In a frightened manner he ran about the pasture, and, strange as it may seem, he finally ran directly toward me, when I shielded myself behind a small tree and took hold of his bridle rein. Blood was trinkling down his shoulder from a wound in top of his neck.

|

Here's how to contribute to the

Save Historic Antietam Foundation:

Donate | Mission | More |

The officer soon approached limpingly, leaning upon a stick. He seemed to think I was the one who had wounded him in the thigh, and raised his hand in token of surrender, saying, "I am your prisoner." I assured him of his safety from further injury as he came up and began patting horse on the neck. He asked why I had shot him in the leg when I could have taken his life. I replied, "There comes the man who can explain," pointing to the skirmisher who was coming near with his still slightly smoking gun. The wounded officer seemed afraid the two Yankees would treat him harshly, but being assured he would be treated as a prisoner should be in civilized warfare, and that I was yet partially disabled, he became more trustful.

The long range sharpshooter explained that the prisoner was sitting with right leg over the horn of his saddle, and that he aimed the bullet to cut the top of the neck of the horse so as to throw the rider and thus make him prisoner without injury, but that it also cut the thigh of the Major. The company of sharpshooters were now on the scene, and their captain tried to determine who captured the horse and man. One thing was certain, I was first in possession of both, though neither one would have come to me without the aid of the sharpshooter. However, the captain decided he could not spare so good a man from his company, and ordered me put in the saddle with the wounded Major behind me to be taken to some general headquarters. I confess I was afraid the stalwart Major might easily kill or capture me in my condition, so the sharpshooter put the prisoner in the saddle, took his revolver from the holster, and led him away, and became the owner of his fine horse as I saw in the papers some time afterwards.

Soon a troop of cavalry came along establishing a picket line, and I was put astride of a horse behind a member of the troop, and was put on one of their reserve posts, where I was tenderly cared for and where I received the first morsel of food I had eaten since the evening before. During the night our picket lines were advanced and I was again taken behind the same cavalry man, and a rough ride I had until we reached a piece of dense woods where I begged him to drop me off his now fractious horse. I lay beside a log all night and became quite chilled by the September breeze.

The morning of the 18th found me near a roadway where I was found and placed in a passing ambulance with others, and all put out at a church house. Here was the most horrifying scene thus far witnessed. Many army surgeons were busy dressing wounds and amputating limbs, and details of men were kept busy wheeling off these dismembered parts and burying them in trenches dug for that purpose.

|

19th Indians Corporal Joshua Jones died

Sept. 28, 1862, 11 days after he was wounded

in the leg at Antietam. He's buried at

Antietam National Cemetery.

(Find A Grave) |

Almost at my feet was a young soldier of a New York infantry regiment with his lower jaw and most all of his tongue cut away by a piece of shell. He was manifesting every evidence of pain and suffering. The remaining part of his tongue and upper throat was so swollen that ever and anon he or one of his two attending comrades would have to insert a small tube made from an elder bush through which to draw his breath of precious air. So great was his misery that he would earnestly plead by every sign possible with every man having a gun to shoot him and end his agony. I almost concluded it would be an act of humanity to do so, but I am glad it was not done, for, strange as it may seem, after long years of wondering as to his ultimate fate, I found him in Hotel Cadilac at the national encampment in Detroit, Mich., in 1891. He had developed into a tall, healthy and dignified man. I guessed his identity by an appendage in the form of a jaw fitted in the place of the one lost.

I had a couple hours talk with him, he replying on his slate, "Yes, then I had many more years of life before me and would have given a million dollars if I had them to give to have been shot; now I would give that amount to keep from being shot," was one of his notable written sentences, with a semblage of a smile. I accepted his invitation to dinner at the Cadilac, where he kept forty-two of his comrades at his expense. I noticed he took his soups and coffee through silver and glass tubes.

I was glad to be taken from this heroic sufferer to Keedysville, where we were all placed on straw on a barn floor. Here [Corporal]

Joshua Jones of my company was brought in on a stretcher. One of his legs was severed, except for a fragment of flesh. Maggots had infested the decaying wound, The surgeons expressed fear that he could not survive the amputation in his extreme weakness, but I saw them remove the limb and he died soon after. I was on the list to be sent to the general hospital at Baltimore, but after being crowded into the ambulance I found I had left my pocket portfolio in the barn, and as it contained the letters and pictures of my mother and the girl I left behind, I went back, and in the long search to find them I missed the ambulance. The surgeon told me to take the next load, but concluded as I had thus far escaped a general hospital, I would try to find my regiment.

|

| "Dead Confederates were being cared for, but their blackened and swollen bodies still dotted the earth," Robert Patterson recalled about the day after the battle. Here are Confederate fallen along Hagerstown Pike. (Library of Congress) |

I presume it was about 8 a.m., when I started. Most of our dead had been buried, and the dead Confederates were being cared for, but their blackened and swollen bodies still dotted the earth until I reached the road leading past a brick Dunkle [Dunker] church where the charred bodies in gray uniform lay side by side along a fence that seemed fully half a mile. I presume most of them were carried there, while many were reclining against the fence or a tree, in which position they were killed on this road of fearful carnage.

|

Captain George Greene was writing the

"obituary" for Patterson when

the wounded private showed up

at the 19th Indiana camp.

(Indiana State Library) |

My march was necessarily slow, with many stops for rest, but I reached the remaining portion of the 19th Indiana encamped on the high banks of the Potomac river before sunset, weak and almost exhausted from my short but dreary march. The few remaining boys of Company E gave me a hearty welcome, as one from the tomb. Captain [George] Green [Greene] sat absent-mindedly writing to my mother, who is yet living, my obituary, paying glorious tribute to my career as a soldier on previous battle fields, and finally bravely meeting death at Antietam by shell that never toched [sic] me, except by concussion.

Captain Green gazed at me in glad bewilderment. It was the first and only time I have ever read my own obituary, and I sincerely hope that I will live out of my remaining earthly life as soldier and citizen that my final obituary may contain as much good as the first.

It was marked, "Rest Without Duty For Thirty Days." Duty soon came with the onward march of the army of the Potomac to further contest of defeats and victories with this great army of treason that might have pushed to annihilation before it could recross the river into Virginia. I have ever been glad that I reached my regiment in time to save that report of my death being sent to the paper at home and to the mother who is still living, and that my own letter reached her instead. I have given only a brief synopsis of the moving scenes that were ever shifting before my gaze. Others saw more and differently, and suffered worse in the battle, and those past and to came, but they are given from my own recollection of the most momentous scenes of fifty years ago today.

— Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

SOURCES:

- Kemper, G. W. H. (General William Harrison), A Twentieth Century History of Delaware County, Indiana, Chicago, Lewis Publishing Co., 1908

- The Life and Times of Robert Patterson," Minnetrista Blogs, accessed Sept. 15, 2019

- The Muncie (Ind.) Morning Star, Sept. 18, 1912, Sept. 30, 1916

- The Star Press, Muncie, Ind., July 1, 1913