Showing posts with label Dunker Church. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Dunker Church. Show all posts

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

No talking: Exploring the Dunker Church at Antietam

Friday, February 23, 2018

Dunker Church hotel? In 1889, an awful idea for Antietam

|

| 1884 photograph of the Dunker Church at Antietam. (Mollus Collection) |

On Oct. 10, 1889, the Hagerstown (Md.) Torch and Light reported that "several New Yorkers" were negotiating to purchase the Dunker Church property with the intention of constructing a "large hotel" there on the Antietam battlefield. "The church building will not be disturbed," the newspaper reported, "but is to be preserved as a distinguishing mark of the battlefield."

Thankfully, this plan never got off the ground.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

Wednesday, January 03, 2018

Hey, Larry David, my daughter loves the Civil War, too!

|

| Jessie Banks and your humble blogger in front of the Dunker Church at Antietam. (CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

Like this blog on Facebook

On the way to her first professional gig in Nashville, Jessie Banks and I decided we absolutely had to stop at Antietam. God bless her. During the drive from the tiny state of Conn., she endured a stream of dad jokes as well as Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Steely Dan, Pearl Jam, Lynyrd Skynyrd and The Rolling Stones. Now on to see where the 15th Massachusetts was routed in the West Woods. She loves this stuff!!!! Take that, Cazzie David.

|

Cazzie David seemed to enjoy a 2015 visit to Manassas battlefield with her funny father, Larry.

(Instagram | @cazziedavid)

|

Thursday, October 06, 2016

Antietam Then & Now: 125th Pa. vets at Dunker Church in 1888

Thursday, September 29, 2016

Antietam Then & Now: Confederate dead near Dunker Church

Sunday, March 20, 2016

Antietam: Details in Gardner's iconic image of fallen Rebels

|

| Alexander Gardner/Library of Congress |

Taken by Alexander Gardner on Sept. 19, 1862, two days after the Battle of Antietam, this photograph of bodies of Confederates gathered for burial is an iconic Civil War image. The renowned photographer took another, similar shot of fallen Rebels near Dunker Church as well as a photograph that focused on the battle-damaged church itself. All these photographs were dissected by William Frassanito in his terrific 1978 book, Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America's Bloodiest Day, and each is available to examine today in high-resolution, TIFF format.on the Library of Congress web site.

The image above has been reproduced countless times in books, magazines, newspapers and online. It also appears on an interpretative marker near the battlefield Visitors' Center, yards from where Gardner set up his camera to shoot the photograph more than 153 years ago. You can even view an impressive, colorized version of one of the images here.

But have you really seen the iconic image at the top of this post? Cropped enlargements of it offer interesting perspectives and perhaps details you have never noticed ...

... this blurry enlargement includes the figures of two horses and at least two people (near entrance and side entrance) at the Dunker Church, which was used as a makeshift field hospital. Easily seen in this enlargement is damage to the small, white-washed brick building, which was struck by artillery and "perfectly riddled" by bullets. "I visited the little church in the edge of the wood but it's nothing but a wreck," 5th Maine Captain Clark Edwards wrote a month after the battle.

Two days after Antietam, Captain George Noyes, a member of General Abner Doubleday's staff, wrote a seering description of the scene at the church:

"A few severely wounded rebels were stretched on the benches, one of whom was raving in agony. Surgical aid and proper attendance had already been furnished, and we did not join the throng of curious visitors within. Out in the grove behind the little church the dead had already been collected in groups ready for burial, some of them wearing our uniform, but the large majority dressed in gray. No matter in what direction we turned it was all the same shocking picture, awakening awe rather than pity, be-numbing the senses rather than touching the heart, glazing the eye with horror rather than filling it with tears."

... this enlargement shows broken fence rails and the heavily contested West Woods beyond. The post-and-rail fences along Hagerstown Pike were well constructed, according to the 106th Pennsylvania regimental historian, who wrote: "... there was a fence on each side of the pike, a strong post and six-railed fence, that the One Hundred and Sixth Regiment had to climb and the mounted officers ride some distance to the right to get through an opening."

Portions of the fence, a frequent target for bullet-hunting souvenir seekers after the battle, survived into the early 20th century. "The old post and race fence that has been standing along the pike north of the Dunkard Church for nearly a half century, and which was marked with hundreds of bullets, has been torn away on the west side," noted Antietam guide O.T. Reilly wrote in the Shepherdstown (W.Va.) Register on May 20, 1909. "It had been hunted over by thousands of persons in hope of finding bullets. A number of panels still stand on the east side, and we hope they will be left for a while yet to show to visitors." (Hat tip: Rare Images of Antietam by Stephen Recker.)

... a dead horse and torn, bloated bodies near a Confederate artillery limber chest ...

... and another dead horse, its hind leg awkwardly in the air, appears in the right background of the damaged negative of this version of Gardner's image. ...

... while in this close-up a fallen Confederate shows us the ugliness of war. Unburied for two days, this soldier's body is bloated as decomposition has begun. The eight dead Confederate soldiers in Gardner's image were likely buried haphazardly in a trench by Union soldiers, who buried their own dead first. After the war, they may have been disinterred and reburied in a Confederate cemetery in Hagerstown, Md., or Shepherdstown, W.Va. ...

... another close-up of fallen Confederate, his trousers perhaps opened by the expansion of gases within his decomposing body. Noyes also described the shocking sight of Rebel dead near the Hagerstown Pike:

"Their faces are so absolutely black that I said to myself at first, this must be a black regiment. Their eyes are protruding from their sockets; their heads, hands, and limbs are swollen to twice their natural size. Ah! there is little left to awaken our sympathy, for all the vestiges of our common humanity which touch the sympathetic chord are now quite blotted out."

... and in the foreground of the original image is this incongruity: a pair of easily overlooked shoes yards from the bodies.

Sunday, March 13, 2016

Antietam: 125th Pennsylvania sergeant saved by wife's photo

|

| SEPT. 17, 1904: 125th Pennsylvania veterans at dedication of the regiment's Antietam monument. |

|

| A post-war image of Edward Russ, who suffered an abdomen wound at Antietam. |

At least five veterans in attendance that late-summer day in 1904 suffered nightmarish experiences at Antietam -- the first battle of the Civil War for the 125th Pennsylvania.

After firing his gun, Private Francis Gearhard of Company D retreated from near the church and joined his comrades, who had re-formed in a line behind a battery. Gearhart found a better musket and picked up a leather case from a dead Confederate that held a knife, fork and spoon. Then "a wounded Reb asked me to help him to a shady place," the immigrant from Germany recalled, "but on getting him to his feet he was unable to walk, as part of his bowels were hanging out, and I was compelled to leave him."

|

| A minister after the war, Elias Zeek was shot in the right arm at Antietam. |

A bullet ripped through the face and neck of Private Stephen Aiken of Company D, breaking his jaw bone and resulting in his discharge from the army in March 1863. After he was wounded and carried from the field by two comrades, Private Michael B. Brenneman of Company C spent 10 days in a battlefield hospital and another five weeks in a Pennsylvania hospital. "...It was two months," he wrote later, "before I got about on crutches."

But perhaps no veteran who attended the dedication of the 125th Pennsylvania monument that day suffered as harrowing an experience during the battle as Edward L. Russ.

|

| Michael B. Breneman spent two months on crutches after he was wounded at Antietam. |

Russ, who had been mustered into the 125th Pennsylvania a little more than a month before Antietam, was rescued by six comrades, who risked their lives by carrying him from his exposed position. A surgeon thought Russ' wound was mortal, but he miraculously recovered at a hospital in nearby Hagerstown, Md., and survived the war. He died on Oct. 30, 1928, and was buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn, N.Y.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES:

--Altoona (Pa.) Mirror, Oct. 8, 1907

--History of The 125th Pennsylvania Volunteers 1862-63, By The Regimental Committee, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1906

Monday, November 10, 2014

Set aside to die, Virginian survived Antietam, war

|

| 30th Virginia Private John Hilldrup was wounded at the Battle of Antietam. (Images courtesy Cindy Abbott, a Hilldrup descendant) |

|

| A post-war image of John Hilldrup |

"The Lord had work for him to do," according to a post-war account, "and that impression bore him up all through his sufferings. ... he did what he could for the spiritual good of the soldiers of his company by holding prayer and other meetings when opportunity offered." A preacher when he joined Company K of the 30th Virginia ("King George Grays"), Hilldrup also survived nearly three more years of the Civil War, surrendering with the rest of Lee's army at Appomattox Courthouse, Va., on April 9, 1865.

After the war, Hilldrup got married, fathered six children and became a prominent Methodist Episcopal preacher known for a strict interpretation of the Bible. "In re-proving sin he was outspoken and pointed," an account noted, "and in some instances, as his best friends thought, a little too personal." When his old war wound plagued him in his later years, "it created homage in the heart," it was noted, "to see him going, often-times in feebleness extreme, from house to house ..."

When Hilldrup died on June 28, 1895, the bullet that wounded him nearly 32 years earlier still remained embedded in his lung. Two days later, he was buried in Scottsville, Va., on what would have been his 55th birthday. (See his gravestone on Find A Grave here.)

Tuesday, October 02, 2012

Antietam: An old battlefield image?

|

| Is this an old photograph of Dunker Church at Antietam? (Connecticut State Library archives) CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE. |

UPDATE FROM STEPHEN RECKER: "Thanks for the kind words. Yes, that is the Hagerstown Pike in a photo taken by John H. Wagoner of Hagerstown in the 1890s. It appears in Martin Burgan's Guide book, published first in 1906. I am raffling a 1928 edition of that guide book this weekend at the Center For Civil War Photography's Antietam Seminar. Again, keep up the great work and thanks for the plug!"

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Antietam: Rare Dunker Church artifact

At the New England Civil War Museum in Rockville, Conn., there are plenty of wonderful artifacts as well as some weird and bizarre ones.

X-ray of a 16th Connecticut Infantry veteran who had a Civil War bullet embedded in his body?

Got it.

Flattened bullet removed from the above soldier?

Check.

|

| In this 1884 photo, two men sit on the front steps of the Dunker Church in Sharpsburg, Md. (Mollus Collection) |

It's there.

Bullet that mortally wounded 21st Connecticut colonel Thomas Burpee at Cold Harbor?

Ditto.

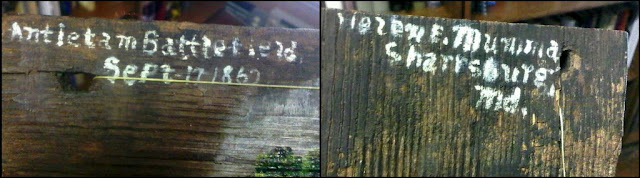

Also among the period letters, rifles, swords and photographs of soldiers is an unusual relic from the Battle of Antietam: a shingle from the Dunker Church, the small, whitewashed building around which savage fighting swirled during the first phase of the bloodiest day in American history.

In the decades after the Civil War ended, Sharpsburg resident Helen Mumma collected original shingles from the Dunker Church and then painted scenes of the small building on them. Mumma sold the shingles at a small souvenir stand in Sharpsburg, according to Matt Reardon, the very enthusiastic executive director of the museum. (See video below.)

Reardon isn't sure how the Dunker Church shingle ended up in the New England Civil War Museum, which is housed in the second floor of what once was the local Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) headquarters. Four Connecticut regiments fought at Antietam, so it's likely a veteran bought it from Mumma and brought it back from Sharpsburg after a trip to the battlefield, Reardon said.

The New England Civil War Museum is only 25 minutes east of Hartford, just off I-84. The museum is open two Sundays a month; admission is free, but donations are accepted. If you're in the area, it's definitely worth a visit.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)