Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter | HELP SAVE THE WALLS

|

| The farmhouse, now in disrepair, dates to the late 18th century. |

“It’s almost like he has reached back in time—I really have affinity for this guy,” says Michael Meehan, who aims to preserve the scrawling in the farmhouse for future generations.

“Just walking into that room in the farmhouse and seeing that man’s name on the wall and you go, ‘Holy cow!’”

Meehan—who grew up in Stewartstown, Pa., roughly 45 miles from Gettysburg, but now lives in Meherrin, Va.—must work fast. Victimized by nature, time, and neglect, Vaughan’s late-18th-century house has nearly deteriorated beyond repair. With the blessing of the farm’s current owner, who acquired the house and surrounding property in 2011, Meehan intends to remove the walls. But he needs the public's help, so he has established a GoFundMe Page to raise $3,500 to defray costs. Ultimately, Meehan and other local preservationists want to have the artifacts displayed in a museum.

|

| A view of the Virginia countryside from the farmhouse. |

On April 6, 1865—three days before Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House—the 105th Pennsylvania fought Confederates near Deatonsville, a continuation of fighting at Saylor’s Creek. Among the regiment's 16 wounded that day were Shivler, Calkins, and Mahorn.

Calkins suffered a wound in his left foot, between his second and third toe, with the bullet coming to rest near his ankle. “It must have been incredibly painful,” Meehan says. Less than a year earlier, he had suffered a wound in the right arm in brutal fighting at the Wilderness. After the war, he married, raised a family, and moved throughout the country.

Meehan identified Mahorn by his initials on the wall, but the nature of the Pennsylvanian’s wounds and his background require more research.

McKechnie, who battled dysentery in 1864, suffered a wound from a stray bullet in his left hand in support of a firing battery near Amelia Springs, Va. The bullet tore through his index finger and middle finger, exiting below the thumb. Following the war, McKechnie—who was probably in his late teens when he enlisted—returned to Maine.

|

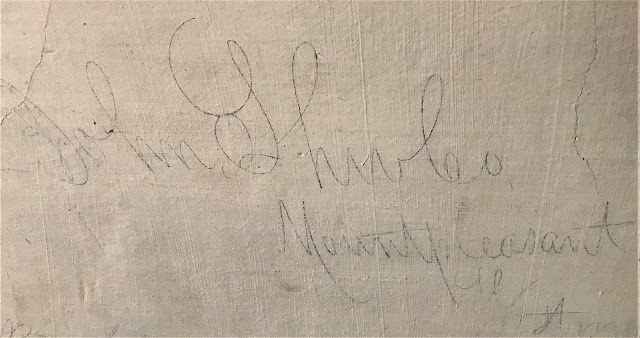

| Near his name, Private Luther Calkins of the 105th Pennsylvania may have drawn the illustration at lower left. |

|

| Severely wounded John Shivler of the 105th Pennsylvania wrote his name on the farmouse wall. |

But it’s the story of Shivler, who served in the 105th Pennsylvania’s color guard, that moves Meehan most.

After a bullet struck the corporal in the face, a 105th Pennsylvania comrade feared he was dead. As Shivler, who was 30 or 31, staggered to his feet, a horse nearly trampled him. He made it to Vaughan's farmhouse, where he received treatment for his wound. Perhaps Vaughan, who remained on his farm during fighting in the area, walked through his house as Shivler and other Federal wounded lay in the cramped quarters.

|

| An illustration from John Shivler's pension file depicts his April 1865 battlefield wound. (Courtesy Michael Meehan) |

In addition to money, the removal of the fragile walls requires expertise. Meehan's brother, a building contractor, will aid the effort. The plan is to cut studs from the walls, put plywood behind and Plexiglas in front of them, squeeze the Civil War treasure together “like a sandwich,” and remove the artifacts.

Meehan will continue to research the backgrounds of each of the ID’d soldiers as well as Truely Vaughan, who owned roughly 1,400 acres, 30 slaves and farmed tobacco, among other crops. Through ancestry.com, a genealogy site/rabbit hole, Meehan has even tracked down descendants of Calkins and McKechnie. The Maine soldier’s descendant was “absolutely stunned” when Meehan contacted her.

Meehan also will continue to research the fighting at Deatonville, the little-known scrap in the war's waning days. "We are still trying to lay out battle there because there are very sparse records on it," he says. Dozens of soldiers wounded from the battle may have been cared for on Vaughan's farm.

For Meehan, the effort brings immense satisfaction.

“I have been passionate about history since I went to Gettysburg when I was 6,” he tells me, "and I’ve been married to it ever since.”

|

| John Shivler's grave in Philipsburg Cemetery in South Philipsburg, Pa. (Find A Grave) |

Great story.

ReplyDeletegreat story

ReplyDelete