|

| In 1894, Frank Leslie's Illustrated published this illustration of Felix Zollicoffer's death at the Battle of Mill Springs (Ky.) on Jan. 19, 1862. (Courtesy of Library Special Collections, WKU) |

"What in hell are you doing here?" a Union officer shouted at the men as the Battle of Mill Springs swirled around them on Jan. 19, 1862. "Why are you not at the stretchers bringing in the wounded?"

|

| Union soldiers derisively called Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer "Snollegoster" and "old he-devil." (Library of Congress) |

"I know that," the officer said. "He is dead and could not be sent to hell by a better man, for Col. Fry shot him; leave him and go to your work."

Earlier that misty, cold morning, Zollicoffer — a former Tennessee congressman and newspaper editor from Nashville — had mistakenly ridden into Union lines. After a brief volley of shots, he fell dead from his horse, struck through the chest. Colonel Speed Smith Fry may have fired the fatal bullet into the 49-year-old commander, whom Union soldiers derisively called “Snollegoster” and an “old he-devil.”

Even in death, Zollicoffer’s body attracted attention. Days after the battle, a New York newspaper correspondent spotted him outside the tent of the 10th Kentucky sutler, wrapped in a blanket. The reporter noted that Zollicoffer’s skin was “beautifully white and clear” and that his face held a “pleasant expression,” which “grim in death was not altogether destroyed.” Zollicoffer had shaved his beard, “probably in order to be less easily recognized,” the correspondent speculated.

But souvenir hunters stripped “Old Zolly” of his clothing, from the rubber coat over his uniform down to his shirt, undershirt and socks. An Ohio private cut three buttons from his coat, and others even clipped his hair close to the skull.

(Click icon at right for full-screen experience.)

But souvenir hunters stripped “Old Zolly” of his clothing, from the rubber coat over his uniform down to his shirt, undershirt and socks. An Ohio private cut three buttons from his coat, and others even clipped his hair close to the skull.

(Click icon at right for full-screen experience.)

|

| The death of General Zollicoffer was front-page news in Northern newspapers. Here's a headline from the Rutland (Vt.) Daily Herald on Jan. 21, 1862. |

"l am sorry to say that his remains were outrageously treated by the thousands of soldiers and citizens that flocked to see them." wrote the New York reporter, probably exaggerating the number of ghouls. (This theft from a fallen officer was not unique: While Union General John Sedgwick's body lay at an embalmer in Washington, "a lady exhibited a singular pertinacity," a newspaper reported, "to procure a memento of the fallen hero by clipping two buttons from his coat.")

Some questioned the accuracy of the report on Zollicoffer, but the evidence seems clear.

|

| Union Colonel Speed S. Fry may have fired the bullet that killed Felix Zollicoffer. (Library of Congress) |

"I have a small piece of Zollicoffer's undershirt," a Federal soldier bragged, "and a daguerreotype of a secession lady, taken with a lot of other plunder." An Ohio newspaper reported a Union officer displaying a piece of the general’s buckskin shirt: “It was very soft, and must have been exceedingly comfortable if kept dry.”

A week after the battle, 31st Ohio Captain John W. Free wrote of soldiers dividing Zollicoffer’s clothes as trophies “until orders were imperatively given not to do so anymore.” He added, “But his pants and the fine buckskin shirt are no doubt scattered all over the different States of the North,” as soldiers from four or five states had been present.

A week after the battle, 31st Ohio Captain John W. Free wrote of soldiers dividing Zollicoffer’s clothes as trophies “until orders were imperatively given not to do so anymore.” He added, “But his pants and the fine buckskin shirt are no doubt scattered all over the different States of the North,” as soldiers from four or five states had been present.

Another Ohioan confirmed Free's account. "When the soldiers saw Zollicoffer’s corpse," wrote Private John Boss of the 9th Ohio, "they tore his clothing from his body, and split up his shirt, in order to have a souvenir. A Tennessean wanted his whole scalp, but was prevented from that because a guard was placed there."

In a letter to a friend, 9th Ohio quartermaster sergeant Joseph Graeff described his own memento of Zollicoffer: "Inclosed you will find a lock of his hair and a piece cut from his pantaloons. Shortly after the battle I hunted for his corpse, and found it lying in the mud."

Eventually, U.S. authorities stopped the macabre souvenir-taking. Zollicoffer’s mud-spattered body was washed and placed under guard in a tent. “Having no clothing suitable in which to dress him,” a witness recalled, “he was wrapped in a nice new blanket until they could be procured, after which he was dressed and provided for in a handsome manner. Particular regard and unusual respect were shown his body by officers and men.”

Chaplain Lemuel F. Drake of the 31st Ohio viewed the general's remains on a board in the tent. "I saw the place where he was shot, and laid my hand upon his broad forehead," he wrote. "He was about six feet tall, and compactly and well built, one of the finest heads I ever saw."

Days after the battle, a Union Army surgeon embalmed Zollicoffer’s body in Somerset, Ky. The remains were placed in a metallic coffin and handed over to the Confederates under a flag of truce. Back in his native Tennessee, soldiers and sympathizers treated one of Nashville’s leading citizens with reverence.

On Feb. 1, the general’s body arrived in Nashville. Despite rainy, “exceedingly disagreeable weather,” thousands filed past the remains at the State Capitol Building. The next day, the procession to Zollicoffer’s grave at Nashville City Cemetery — a little over a mile away — was described as “one of the largest ever seen” in the city.

Among the mourners were his five daughters: Virginia, 24; Ann Maria, 17; Octavia Louise, 15; Mary Dorothy, 12; Felicia, 7; and Loulie, 5. Zollicoffer’s wife, Louisa Pocahontas, had died in 1857.

|

| Joseph Graeff got a lock of Zollicoffer's hair and a "piece cut from his pantaloons." (Courtesy 9th Ohio Infantry site) |

Eventually, U.S. authorities stopped the macabre souvenir-taking. Zollicoffer’s mud-spattered body was washed and placed under guard in a tent. “Having no clothing suitable in which to dress him,” a witness recalled, “he was wrapped in a nice new blanket until they could be procured, after which he was dressed and provided for in a handsome manner. Particular regard and unusual respect were shown his body by officers and men.”

Chaplain Lemuel F. Drake of the 31st Ohio viewed the general's remains on a board in the tent. "I saw the place where he was shot, and laid my hand upon his broad forehead," he wrote. "He was about six feet tall, and compactly and well built, one of the finest heads I ever saw."

|

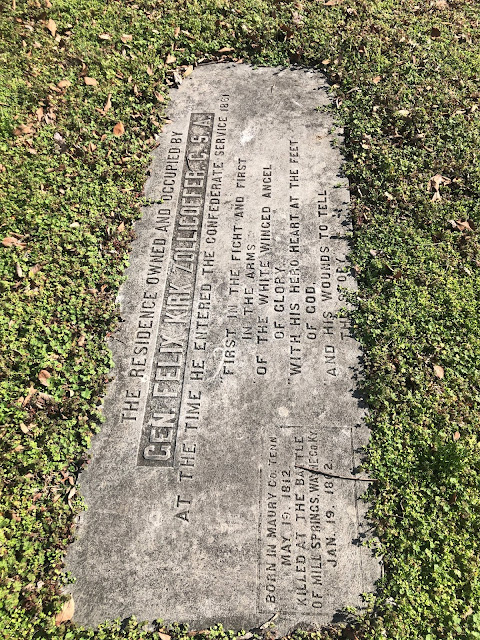

| Inscription on Felix Zollicoffer's marker in Old Nashville (Tenn.) City Cemetery. |

On Feb. 1, the general’s body arrived in Nashville. Despite rainy, “exceedingly disagreeable weather,” thousands filed past the remains at the State Capitol Building. The next day, the procession to Zollicoffer’s grave at Nashville City Cemetery — a little over a mile away — was described as “one of the largest ever seen” in the city.

Among the mourners were his five daughters: Virginia, 24; Ann Maria, 17; Octavia Louise, 15; Mary Dorothy, 12; Felicia, 7; and Loulie, 5. Zollicoffer’s wife, Louisa Pocahontas, had died in 1857.

“First in the fight,” reads the inscription on a marker next to Zollicoffer’s gravestone, “and first in the arms of the white-winged angel of glory, with his hero heart at the feet of God and his wounds to tell the story.”

SOURCES

|

| Felix Zollicoffer's gravestone and marker (below) in Old Nashville City Cemetery. |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES

- 9th Ohio Private John Boss letter from Camp Hamilton, Jan. 22, 1862, 9th Ohio Infantry web site, accessed March 13, 2020

- Cincinnati Daily Press, Feb. 8, 11, 1862

- Detroit Free Press, Jan. 25, 1862

- Perry County Weekly, New Lexington, Ohio, Feb. 5, 1862 (transcribed by Jo An Sheely via excellent Death of Felix K. Zollicoffer section by Geoffrey R. Walden on the Experience Mill Springs website. Walden's page also includes a passage from Jan. 24, 1862, letter by Private Thomas Porter of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery, who wrote of cutting off buttons from Zollicoffer's coat. Accessed March 10, 2020.)

- Philadelphia Press, Jan. 21, 1862

- The Bucyrus (Ohio) Journal, Jan. 31, 1862

- The Cincinnati Commercial, February 1862

- The Cincinnati Enquirer, Jan. 25, 1862

- The Daily Register, Knoxville, Tenn., Feb. 4, 1862

- The Washington Star, May 12, 1864

No comments:

Post a Comment