|

| Of Gordon Rhea's five Overland Campaign books, his Cold Harbor work is the only one MIA in my library. |

Like this blog on Facebook | More Civil War Q&As on my blog

|

| Gordon Rhea |

I was impressed with the well-spoken Rhea's knowledge and especially by his passion for writing. That's no accident.

"When I was in college," he told me via e-mail, "the professor who guided me in writing my history honors thesis insisted on a clear and interesting writing style. I have taken to heart his admonition that history must be interesting to read, or no one will read it."

In an e-mail Q&A for my blog, Rhea also writes of the battlefield spot he finds most moving, his hope the National Park Service and relic hunters can work with each other, the greatest myth about the Overland Campaign and more.

|

| Winslow Homer's "Skirmish in the Wilderness" evokes the "dark mood of a confused battle," Rhea says. |

Winslow Homer's painting "Skirmish In the Wilderness," in the collection of the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, appears on the cover of your first Overland Campaign book, The Battle of the Wilderness, May 5-6, 1864. Why was that chosen, and what reaction do you have when you see it?

Rhea: For each of my books, I have tried to select art by a painter of the Civil War generation who best captured the mood of the narrative, Winslow Homer's painting of the Wilderness fighting certainly meets that objective. It evokes the dark mood of a confused battle in a thick woodland where neither soldiers nor generals knew where the enemy might be, a battle of ghostly figures against ghostly figures.

For my book about Spotsylvania Court House, I chose Julian Scott's painting of the death of General John Sedgwick, who was killed by a Confederate sharpshooter. Like Homer, Scott served during the Civil War, and his painting evokes an authentic contemporary mood.

Finding a painting for my book about the North Anna River proved more difficult, as no artists who had experienced the Civil War chose that battle for a painting. However, a modern artist in Fredericksburg -- Donna J. Neary -- painted an excellent piece entitled "Even to Hell Itself" depicting Lieutenant Colonel Charles L. Chandler trying to rally his troops during General James H. Ledlie's ill-fated attack at Ox Ford. Ms. Neary courteously permitted me to use her fine piece for my cover.

For my Cold Harbor book, I returned to Julian Scott, this time using his painting of Theodore Lyman attempting to deliver a message across enemy lines to facilitate the removal of dead and wounded soldiers from the Cold Harbor battlefield.

As with my North Anna book, I could find no paintings of the movement across the James River and the initial assault toward Petersburg. An impressive black-and-white image is an 1897 drawing by Benjamin West Clinedinst depicting Grant watching the Army of the Potomac crossing the James. The drawing appeared in Horace Porter's Campaigning With Grant, and LSU Press used modern technology to colorize if for my cover.

|

| From left, generals James Wadsworth, John Sedgwick and J.E.B.Stuart. Each died from battle wounds. |

In your Wilderness book, I was fascinated by the story of the death of Union General James Wadsworth, who was shot in the head and died behind Confederate lines. Of the deaths of soldiers you have told in your books, which story resonates most with you?

Rhea: The story of Wadsworth's death is certainly moving, as are the circumstances of John Sedgwick's death. Perhaps the most heart-rending deathbed scene is that of Jeb Stuart, who was brought back to Richmond following his mortal wounding at Yellow Tavern and died before his wife could reach his side.

Given the access to materials online today, how is the research process different for you for your most recent book compared with the process for your first Overland Campaign book published in 1994?

Rhea: I began working on my Wilderness book in 1986. Then, of course, there were no online resources, so I spent considerable time traveling around the country visiting archives and gathering material. Bob Krick at the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park had done a wonderful job collecting primary sources, and I spent several days working through that treasure trove of information. I also received assistance from researchers such as Bryce Suderow, who introduced me to the world of Civil War-era newspapers. Back then, they were accessible only through microfilm or in the jurisdictions where they had been published.

The Internet has eased the difficulty of researching somewhat, although not entirely. Many Civil War-era newspapers are now online, as are older books and some letters and diaries. While many major repositories have put indexes online, to see the actual documents you generally have to visit the repositories. In short, researching the Civil War still requires lots of travel.

|

| Higgerson Farm, one of the few clearings in the Wilderness. "One cannot fathom the true nature of a battle without walking the ground," Gordon Rhea says. |

(Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

You believe it's essential to walk the ground of a battlefield before writing about the fighting there. Tell us about that.

Rhea: One cannot fathom the true nature of a battle without walking the ground. The lay of the land explains much about what happened and what did not happen. Years ago, I led a tour of the Wilderness battlefield for the U.S. Army's Training and Doctrine Command. My audience included veterans of Vietnam and of the first Gulf War. After the tour, we gathered around a table and talked about the differences and similarities between modern warfare and warfare in the 1860s. The modern-day warriors were most impressed with the difficulty of managing and maneuvering Civil War armies. Without aerial observations or electronic communications, it was impossible to know if the enemy was 50 miles away or just over the next ridge. And with battle lines stretching for miles, precious minutes -- even hours -- were consumed getting important information to headquarters and receiving instructions back from headquarters. These modern warriors were very impressed that Civil War commanders were able to get anything right with such primitive intelligence gathering and communications systems.

|

| Post-war image looking from Bloody Angle, the battlefield spot that "always moves" Gordon Rhea, toward the McCoull farm. |

Of the major Overland Campaign battlefields, I find Cold Harbor to be the most haunting, especially where the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery fought. Is there a place on any of the battlefields you have written about that "haunts" you?

Rhea: The Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania Court House always moves me. This was the scene of the war's most vicious, prolonged, face-to-face intense combat. Several years ago, I wrote a book entitled Carrying The Flag that told the story of Charles Whilden, who carried the flag of the 1st South Carolina during the Confederate counter-offensive to retake that stretch of earthworks. I can't help thinking about Charles, an aging conscript who suffered from epilepsy, whenever I visit the site.

|

| Rhea says relic hunters were "very useful" to him at the Wilderness. |

Rhea: I have found relic hunters to be very useful, particularly at the Wilderness battlefield. The only way to accurately determine the position of the various lines in much of that dense woods is to find relics from the battle. Much of the battlefield is outside National Park Service property, and I have spent many hours with relic hunters who showed me where they had determined the battle lines to have been based on the unexpended ammunition (often dropped by soldiers firing and loading as quickly as they could) and expended rounds. I wish that the Park Service could reach an accommodation with relic hunters, permitting them onto NPS lands on designated days on the condition that they share with the park the identity and location of their finds. Seems to me that both parties would benefit from such an arrangement.

What's the greatest misconception about the Overland Campaign?

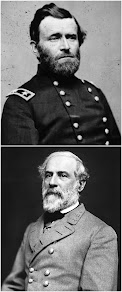

Rhea: That Ulysses Grant was a butcher who never maneuvered, and that Robert E. Lee possessed the extraordinary ability to accurately predict Grant's next move. As my five books on the campaign demonstrate in detail, Grant relied on a mix of attacks and maneuvers to bring his wily adversary to bay, and Lee frequently misjudged Grant's next move, often putting his army in peril.

|

| Ulysses Grant and Robert E. Lee. |

Rhea: It takes a long time and is very painful. I prepare folders for each brigade involved in the battle that I am writing about, and put in each folder excerpts from the pertinent published material, such as regimental histories, memoirs, and newspaper accounts, as well as archival material, including letters, diary entries and the like. From that I can construct what happened, who attacked whom, and what it was like to be there. I write on a computer, so I am able to insert new material as I find it as I go along. Unlike some authors, I cannot get it right the first time. I do multiple drafts, and once I am finished, I print out the chapters and read them both single-spaced and double-spaced, working to get the language right. When I was in college, the professor who guided me in writing my history honors thesis insisted on a clear and interesting writing style. I have taken to heart his admonition that history must be interesting to read, or no one will read it.

Of the books you have written on the Overland Campaign, which one do you step back and say, "Dang, I really nailed that one"? And why is that?

Rhea: I have enjoyed them all. When I began writing about the Overland Campaign, I ventured into uncharted territory. There was only one modern book on the Wilderness (Ed Steers' piece) and none about Spotsylvania, the North Anna, Cold Harbor or the movement to the James River.

If you could ask Ulysses Grant or Robert E. Lee one question about the Overland Campaign, what would it be?

Rhea: I would ask each of them if, knowing what we now know, would they have fought their campaign differently. Would Lee still have tried to hold the line of the Rapidan River, or would Grant now wish he had followed the strategy that he initially advocated -- to first sever Lee's supply lines by advancing from the coast into North Carolina, then pursue Lee as he retired, most likely westward? Also, I would very much like to know Grant's candid opinion whether he would have wanted someone other than George Meade commanding the Army of the Potomac, and someone other than Benjamin Butler commanding the Army of the James.

Finally, what is the greatest void in Civil War writing today?

Rhea: While much has been written about battles, there is still much to be said about the home fronts. We have seen some excellent recent studies of the impact of the war on home life in the Confederacy, but I can't recall any modern studies about how the families of soldiers from the North fared and evolved.

Great interview. Thank you so much for sharing it with us.

ReplyDeleteGordon Rhea retelling the story of Charles Whilden in person was one of my all time favorite moments.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteI very much enjoyed this interview, as I have enjoyed all of Mr. Rhea's works. Thanks for doing it!

ReplyDeleteMr.Rhea is one of my 2-3 favorite authors about the Civil War. I have his previous 4 books and will now buy his 5th.

ReplyDeleteLike Rhea I, too, find the Bloody Angle at Spotsylvania the most moving place of all the battlefields I've walked, although the cornfield, Bloody Lane and Burnside Bridge at Antietam all move me, as well. I had the privilege of visiting the Bloody Angle on a warm, sunny June day a few years ago, and had all of Spotsylvania Battlefield to myself, nary another human. It was eerie and sad, sad for what had happened where I stood, and sad that no other Americans cared enough to be there, too.

ReplyDelete