|

| A white mob lynched 18-year-old Henry Choate from the second-floor balcony of the Maury County Courthouse in Columbia, Tenn., on Nov. 11, 1927. (CLICK ON ALL IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

|

| Deary Armstrong's tilted marker in Salem Church Cemetery. |

Nearby, across an unremarkable two-lane road, broken markers peek from the ground at unkempt Salem Church Cemetery, the final resting place of scores of African Americans. Behind a twisted iron fence sits a large, toppled marker. The gravestone for Marsh Mayes — age 99 years, four months and 22 days — leans against a tree. Weeds and purple wildflowers nearly obscure Deary Armstrong’s tombstone. Dixie Lou Bates’ marker – she was 24 when she died in 1943 – seems forlorn among stumps and trees. The inscriptions on many of the battered gravestones are indecipherable.

|

| “Watch out for the holes,” warned a woman who lives next to Salem Church Cemetery. Some of the graves have subsided, giving the grounds the look of a World War I battlefield. |

|

| The Salem Church Cemetery gravestone of Marsh Mayes, who almost lived a century. |

“Watch out for the holes,” a woman who lives nearby warns me. Subsidence gives the grounds the look of a World War I battlefield in France or Belgium. Clumps of weeds poke from the earth. Bordering the cemetery is a ditch filled with stagnant water — an exclamation point of gloom.

|

| Could this be Henry Choate's gravestone? |

And then there’s the Choates’ 18-year-old son, Henry, who died in 1927. Perhaps he rests beneath the small block marker inscribed with “H.S.C.” None of the last names on the other nearby graves are readable, so there’s no way for me to tell. I know the cause of Henry’s death, though. In cursive writing, it leaps from the page of his death certificate:

“Lynched.”

Henry Choate is why I’m here.

|

| Henry Choate's death certificate. Cause of death: "Lynched." (Courtesy Tina Cahalan Jones) |

'Maury County had been disgraced'

The Page 1 headlines in the Nashville Tennessean on Nov. 12, 1927, are jarring:“Negro Lynched in Columbia for Attack on Girl.”

“Unmasked Mob Estimated at 350 Men Storms Jail With Sledge Hammers.”

“Deaf to Pleas.”

|

| Front-page headlines in the Nashville Tennessean on Nov. 12, 1927. |

The circumstances of Henry Choate’s lynching on Armistice Day 1927 are especially revolting.

Earlier that day, Choate had been accused of assaulting Sarah Harlan, a 16-year-old white girl, as she waited for a school bus on a remote stretch of road five miles from Columbia. Choate denied he was the attacker.

The assailant reportedly nearly tore away Harlan’s clothing and attempted to shoot her. She screamed. According to the Tennessean, the attacker struck her on the forehead with the butt of a pistol and apparently attempted to strangle the teen, one of nine children raised by a widow. Sarah scratched her assailant and bit his finger, drawing blood. The assailant fled when she told him her brother was approaching, a ruse.

“Now I’ll guess you’ll get it,” Harlan said, the Tennessean reported.

Using bloodhounds named Queen and George, a law enforcement posse went to the house of Choate’s grandfather, where they arrested Henry. According to officers, Choate had changed from his bloody shirt and trousers and hidden a 22-caliber pistol, which they alleged he used to club Sarah. Sheriff Luther Wiley said Choate had a wound on the middle finger of his left hand, a bite mark inflicted by the victim. Whether any of this is true, well, we may never know.

Law enforcement took Choate to the house of Harlan’s uncle, where Sarah was staying. She couldn’t identify him positively as her assailant. A mob formed and surged into the house. The girl’s mother and the sheriff “asked them to spare the negro for trial,” the newspaper reported. Officers rushed Choate out another door and then by car to the Maury County Jail, 300 yards from the county courthouse.

Eager to storm the jail, a white mob formed at the two-story, late-19th-century building on 6th Street. Attempts to swipe the keys to the jail from Wiley’s wife failed. Deputy sheriff Ed Pugh of Nashville, who owned bloodhounds George and Queen, warned the crowd about attempting to exact its perverted version of justice on the eve of the election for county sheriff. Wouldn’t want to make Sheriff Wiley look bad after all.

Country star Jason Aldean films music video at lynching site

"Go ahead back to your banquet!" shouted someone in the lynch mob. "You are having your fun over there. Now let us alone while we have ours out here."

“Success of the lynching” the Tennessean reported, was announced by Finney at the American Legion banquet.

“Maury County,” the newspaper later wrote, “had been disgraced.”

Newspapers throughout the United States published accounts of the horror.

In Tennessee, newspapers blamed Sheriff Wiley for not protecting Choate. “One shot fired into that crowd,” a Clarksville newspaper wrote, “would have saved that negro’s life. Mobs are always cowardly under such circumstances as that.”

Beyond demanding justice, however, journalists apparently didn't do any digging of their own into who committed the reprehensible act. A grand jury was convened, but no charges were ever filed. It was “unable to find evidence upon which to return a true bill against participants," a newspaper reported.

SOURCES

|

| The Nashville Tennessean published Sarah Harlan's photo on Nov. 13, 1927. She couldn't positively indentify Henry Choate as her assailant. |

Law enforcement took Choate to the house of Harlan’s uncle, where Sarah was staying. She couldn’t identify him positively as her assailant. A mob formed and surged into the house. The girl’s mother and the sheriff “asked them to spare the negro for trial,” the newspaper reported. Officers rushed Choate out another door and then by car to the Maury County Jail, 300 yards from the county courthouse.

Eager to storm the jail, a white mob formed at the two-story, late-19th-century building on 6th Street. Attempts to swipe the keys to the jail from Wiley’s wife failed. Deputy sheriff Ed Pugh of Nashville, who owned bloodhounds George and Queen, warned the crowd about attempting to exact its perverted version of justice on the eve of the election for county sheriff. Wouldn’t want to make Sheriff Wiley look bad after all.

Country star Jason Aldean films music video at lynching site

At 7 p.m., the scene at the county jail was calm. But about an hour later, the mob formed again on 6th Street, soon growing to about 350. Swinging sledgehammers, men broke into the jail, leaving destruction in their wake. Wiley reportedly pleaded with them to stop. So did his wife, but someone turned over the key to the cell for Choate, who must have been terrified. The sheriff himself may have unlocked the cell.

Nearby, James Finney, the editor of the Nashville Tennessean, and several ministers were attending an American Legion Armistice Day banquet. Alerted to the disturbance at the jail, they attempted to intervene.

Nearby, James Finney, the editor of the Nashville Tennessean, and several ministers were attending an American Legion Armistice Day banquet. Alerted to the disturbance at the jail, they attempted to intervene.

"Go ahead back to your banquet!" shouted someone in the lynch mob. "You are having your fun over there. Now let us alone while we have ours out here."

Finney and a Presbyterian minister — “a critic of hooded orders,” a reference to the Klu Klux Klan — attempted to contact the governor of Tennessee by “long-distance telephone” for assistance from the state militia, stationed nearby. They apparently failed.

“They planned to tell the governor,” the newspaper reported, “that no determined effort was being made to protect the negro against the lynchers."

Dragged from the jail, Choate supposedly confessed at the door of the courthouse to J.R. Parsons, a Methodist minister, who urged the mob to let the teen stand trial. Choate's alleged “confession” was heard by a man nearby holding a rope.

“They planned to tell the governor,” the newspaper reported, “that no determined effort was being made to protect the negro against the lynchers."

Dragged from the jail, Choate supposedly confessed at the door of the courthouse to J.R. Parsons, a Methodist minister, who urged the mob to let the teen stand trial. Choate's alleged “confession” was heard by a man nearby holding a rope.

“Well, that sends you to hell,” the man said, according to a newspaper reporter.

Full of fury and hate, the mob took Choate, a noose around his neck, to the second floor of the courthouse, decorated with red, white and blue flourishes for Armistice Day. The men pushed through the double doors that led outside, tied the rope to the stone balustrade and hurled Choate over.

Full of fury and hate, the mob took Choate, a noose around his neck, to the second floor of the courthouse, decorated with red, white and blue flourishes for Armistice Day. The men pushed through the double doors that led outside, tied the rope to the stone balustrade and hurled Choate over.

A newspaper account said the battered teen may have been dead — stabbed, perhaps. or bludgeoned with a sledgehammer — before the mob tossed him over the edge. Choate's body dangled to about the center of the first-floor doorway for about 10 minutes. Relatives later retrieved his battered remains.

“Success of the lynching” the Tennessean reported, was announced by Finney at the American Legion banquet.

“Maury County,” the newspaper later wrote, “had been disgraced.”

'Courthouse is lynch gallows'

“Courthouse is lynch gallows,” proclaimed the headline in the New York World.

"Tennessee Whites Close Armistice Day With Lynching," read another in The Black Dispatch of Oklahoma City.

"The youth was hanged from the balcony of the courthouse, from which speakers during the day had spoken in eloquent terms of America's part in the Great World War and had pointed proudly to the flag as emblem of justice, protection and freedom for oppressed people," the newspaper told its African American readership.

The Black Dispatch contrasted the banquet gathering that included white ministers with the horror that had occurred at the courthouse.

"In the memorial Building the spirit of patriotism which led 400,000 Negroes in the World War was being expressed," it wrote. "In front of the courthouse was the usual Southern patriotism being enacted."

"In the memorial Building the spirit of patriotism which led 400,000 Negroes in the World War was being expressed," it wrote. "In front of the courthouse was the usual Southern patriotism being enacted."

|

| The day after the lynching, Luther Wiley lost in the Democratic primary for Maury County sheriff. |

The Bristol (Tenn.) Herald Courier, meanwhile, railed against "mob lawlessness."

"If the members of this mob are not hunted down and punished, would-be lynchers will have little reason to be deterred by any fear of the consequences to themselves of their lawlessness, and Tennessee will have the rule of the mob instead of the rule of the law when and where the mob cares to rule," it wrote.

"If the members of this mob are not hunted down and punished, would-be lynchers will have little reason to be deterred by any fear of the consequences to themselves of their lawlessness, and Tennessee will have the rule of the mob instead of the rule of the law when and where the mob cares to rule," it wrote.

A week after the lynching, editor Finney of the Tennessean weighed in on the pages of his influential newspaper. “Executions by mob are murder,” he wrote, “nothing more, nothing less.”

Maury County citizens, a Chattanooga newspaper wrote, “will not be judged alone by the lynching of Henry Choate, but also what they do toward bringing the lynchers to the bar of justice and seeing that they are properly punished for their crime against the state of Tennessee.”

Beyond demanding justice, however, journalists apparently didn't do any digging of their own into who committed the reprehensible act. A grand jury was convened, but no charges were ever filed. It was “unable to find evidence upon which to return a true bill against participants," a newspaper reported.

Predictably, a judge called Maury County law enforcement “blameless.”

The only "justice" in this case came on Election Day, Nov. 12, 1927. Luther Wiley — who “stood by and meekly submitted to the battering down of the doors of his jail,” according to an account — was defeated in the Democratic primary, squashing his bid for a third term as county sheriff.

The only "justice" in this case came on Election Day, Nov. 12, 1927. Luther Wiley — who “stood by and meekly submitted to the battering down of the doors of his jail,” according to an account — was defeated in the Democratic primary, squashing his bid for a third term as county sheriff.

The scene of the crime

|

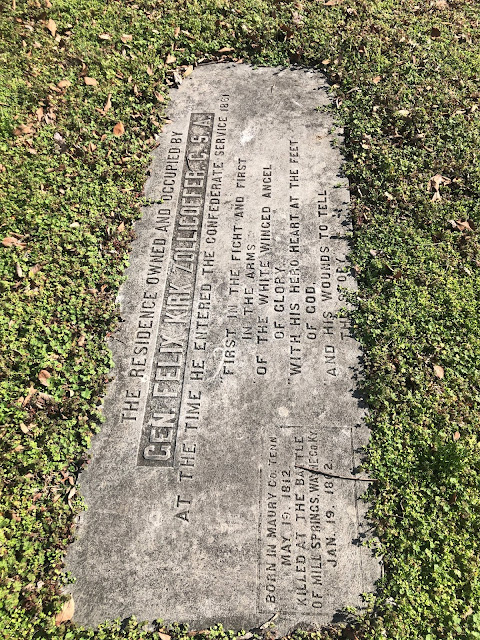

| Maury County Courthouse in Columbia, Tenn. A white mob lynched Henry Choate, a Black teen, from the second-floor balcony in 1927. |

On an overcast Saturday afternoon, I explore the scene of this horror. The three-story Maury County Courthouse, completed in 1904, still stands. A massive American flag flutters above the second-floor balcony — the same balcony from which Choate’s battered body swayed at the end of a rope.

Armed with questions, I circle the building, looking for a marker explaining what happened here on a Monday night nearly 93 years ago. Steps from the front door of the courthouse, dozens of names of U.S. Colored Troops appear on a modern gray-granite soldiers’ memorial. But there’s no mention of a lynching anywhere on the courthouse grounds.

Nearby, Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” blares from a music store. Outside the barber shop next door, I chat with a stylist named Todd. I explain why I'm here: “Black kid … lynched … 1927 … right over there ... from the courthouse balcony.”

"No kidding," he says. He had cut the hair of three customers recently who talked about the lynching.

Armed with questions, I circle the building, looking for a marker explaining what happened here on a Monday night nearly 93 years ago. Steps from the front door of the courthouse, dozens of names of U.S. Colored Troops appear on a modern gray-granite soldiers’ memorial. But there’s no mention of a lynching anywhere on the courthouse grounds.

Nearby, Stevie Wonder’s “Superstition” blares from a music store. Outside the barber shop next door, I chat with a stylist named Todd. I explain why I'm here: “Black kid … lynched … 1927 … right over there ... from the courthouse balcony.”

"No kidding," he says. He had cut the hair of three customers recently who talked about the lynching.

"The old locals here know everything," Todd tells me.

Perhaps my questions are unanswerable, but I have so many. Maybe the locals can help.

Who was Henry Choate?

What might I find in the records of that long-ago grand jury in the county archives?

What happened to Sarah Harlan?

Perhaps my questions are unanswerable, but I have so many. Maybe the locals can help.

Who was Henry Choate?

What might I find in the records of that long-ago grand jury in the county archives?

What happened to Sarah Harlan?

Who was in that white lynch mob?

And, most importantly: Who put that rope around an 18-year-old kid's neck and lynched him in 1927?

And, most importantly: Who put that rope around an 18-year-old kid's neck and lynched him in 1927?

|

| A view of the "lynching porch." |

— Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES

- Bristol (Tenn.) Herald Courier, Nov. 13, 1927

- Chattanooga Daily Times, Nov. 27, 1927

- Find A Grave

- Lancaster (Pa.) New Era. Associated Press account

- Morristown (Tenn.) Gazette, Nov. 15, 1927

- Nashville Tennessean, Nov. 12, 13, 18, 1927

- The Black Dispatch, Oklahoma City, Dec. 1, 1927

- The Leaf-Chronicle, Clarksville, Tenn., Nov. 14, 1927.