Think about what many 16-year-olds do today. Learn to drive a car. Sneak a beer in the woods behind their parents' house. Date. Play video games. Shoot hoops in a high school gym.

, a private in the 11th New York Light Artillery, watched soldiers shoot to kill in godforsaken thickets and woods in Virginia. The teen, who joined in on the bloodletting himself, witnessed up close the gruesome results of warfare.

"A dead sergeant lay at my feet, with a hole in his forehead just above his left eye," Wilkeson wrote about his experience at the Battle of the Wilderness on May 5, 1864. "Out of this wound bits of brain oozed and slid on a bloody trail into his eye and thence over his cheek to the ground. I leaned over the body to feel of it. It was still warm. He couldn't have been dead for over five minutes."

A son of a well-known journalist, Wilkeson enlisted in 1864 after running away from home. On July 1, 1863, his older brother Bayard, a lieutenant in the 4th United States Regular Artillery, suffered a mortal wound at Gettysburg.

After the war, Wilkeson became a journalist, and in 1886, a book of his war-time experiences was published.

is an eloquent, and unvarnished, look at war. Wilkeson's Chapter 11, "

without the images.

At the Wilderness, Wilkeson eagerly joined the battle, although the 11th New York Light Artillery had no fighting role at the time. Here's his remarkable Wilderness battle account from his book, excerpted and published in U.S. newspapers in the summer of 1886:

On the night of May 4. 1864, I slept under a caisson that stood in park close to the Chancellorsville House, in Virginia. I was awakened by a bugle call to find the battery I belonged to almost ready to march. I hurriedly toasted a bit of pork and ate it, and quickly chewed down a couple of hard tack and drank deeply from my canteen, and was ready to march when the battery moved.

It was a delightful morning. Almost all the infantry which had been camped around us the previous evening had disappeared. We struck into the road, passed the Chancellorsville House, turned to the right and marched up a broad turnpike toward the Wilderness forest. After marching on this road for a short distance we turned to the left on an old dirt road, which led obliquely into the woods. The picket firing had increased in volume since the previous evening, and there was no longer any doubt that we were to fight in the Wilderness.

The firing was a pretty brisk rattle, and steadily increasing in volume. About 10 o'clock in the morning the soft, spring air resounded with a fierce yell, the sound of which was instantly drowned by a roar of musketry, and we knew that the battle of the Wilderness had opened. The battery rolled heavily up the road into the woods for a short distance, when we were met by a staff officer, who ordered us out, saying:

"The battle has opened in dense timber. Artillery cannot be used. Go into park in the field just outside the woods."

We turned the guns and marched back and went into the park. Battery after battery joined us, some coming out of the woods and others up the road from the Chancellorsville House, until some 100 guns or more were parked in the field. We were then the reserve artillery.

|

| Union VI Corps fights unseen enemy in the woods at the Wilderness. (Edwin Forbes | Library of Congress) |

Ambulances and wagons loaded with medical supplies galloped onto the field, and a hospital was established behind our guns. Soon men, singly and in pairs or in groups of four or live, came limping slowly or walking briskly, with arms across their breasts and their hands clutched into their blouses, out of the woods. Some carried their rifles. Others had thrown them away. All of them were bloody. They slowly filtered through the immense artillery camp, and asked with bloodless lips to be directed to a hospital.

Powder smoke hung high above the trees in thin clouds. The noise in the woods was terrific. The musketry was a steady roll, and high above it sounded the inspiring charging cheers and yells of the now thoroughly excited combatants. At intervals we could hear the loud report of Napoleon guns, and we thought that Battery K of the Fourth United States Artillery was in action.

By 11 o clock the wounded men were coming out of the woods in streams, and they had various tales to tell. Bloody men from the battle line of the Fifth Corps trooped through our park supporting more severely wounded comrades. The battle, these men said, did not incline in our favor. They insisted that the Confederates were in force, and that they, having the advantage of position and knowledge of the region, had massed their soldiers for the attack and outnumbered us at the points of conflict. They described the Confederate fire as wonderfully accurate. One man who had a ghastly flesh wound across his forehead said: "The Johnnies are shooting to kill this time, few of their balls strike the trees higher than ten feet from the ground. Small trees are already falling, having been cut down by rifle balls. There is hardly a Union battery in action," he added, after an instant's pause.

By noon I was quite wild with curiosity, and, confident that the artillery would remain in the park, I decided to go to the battle line and see what was going on. I neglected to ask my captain for permission to leave the battery, because I feared he would not grant my request, and I did not want to disobey orders by going after he had refused me. 1 walked out of camp and up the road. The wounded men were becoming more and more numerous. 1 saw men, faint from loss of blood, sitting in the shade cast by trees. Other men were lying down. All were pale, and their faces expressed great physical suffering.

As l walked I saw a dead man lying under a tree which stood by the roadside. He had been shot through the chest, and had struggled to the rear; then, becoming exhausted or choked with blood, he had lain down on a carpet of leaves and died. His pockets were turned inside out. A little further on I met a sentinel standing by the roadside. Other sentinels paced to and fro in the woods on each side of tho road, or stood leaning against trees, looking in the direction of the battle line, which was far ahead of them in the woods. I stopped to talk to the guard posted on the road. He eyed me inquiringly, and answered my question as to what he was doing there, saying: "Sending stragglers back to the front." Then he added, in an explanatory tone: "No enlisted men can go past me to the rear unless be can show blood.''

He turned to a private who was hastening down the road, and cried:

"Halt!"

The soldier who was going to the rear paid no attention to the command. Instantly the sentinel's rifle was cocked, and it rose to his shoulder. He coolly covered the soldier, and sternly demanded that he show blood. The man had none to show. The cowardly soldier was ordered to return to his regiment, and, greatly disappointed, he turned back. Wounded men passed the guard without being halted. These guards seemed to be posted in the rear of the battle lines for the express purpose of intercepting the flight of cowards. At the time it struck me as a quaint idea to picket the rear of an army which was fighting a desperate battle.

I explained to the sentinel that I was a light artilleryman, and that I wanted to see the fight.

"Can I go past you?" I inquired.

"Yes," he replied, "you may go up. But you had better not go," he added. "You have no distinctive mark or badge on your dress to indicate the arm you belong to. If you go up you may not be allowed to return, and then, he added, as he shrugged his shoulders indifferently, "You may get killed. But suit yourself."

So I went on.

|

| Union V Corps soldiers receive ammunition while under enemy fire. (Alfred Waud | Library of Congress) |

There was a very heavy firing to the left of the road in a chapparal of brush and scrubby pines and oaks. There the musketry was a steady roar, and the cheers and yells of the fighters incessant. I left the road and walked through the woods towards the battle grounds, and met many wounded men who were coming out. They were bound for the rear and the hospitals. Then I came on a body of troops lying in reserve, a second line of battle, I suppose. I heard the hum of bullets as they passed over the low trees. Then I noticed that small limbs of trees were falling in a feeble shower in advance of me. It was as though an army of squirrels were at work cutting off nut and pine cone-laden branches preparatory to laying in their winter's store of food. Then, partially obscured by a cloud of powder smoke, I saw a straggling line of men clad in blue. They were not standing as if on parade, but they were taking advantage of the cover afforded by the trees, and they were tiring rapidly. Their line officers were standing behind them or in line with them. The smoke drifted to and fro, and there were many rifts in it. I saw scores of wounded men. I saw many dead soldiers lying on the ground, and I saw men constantly falling on the battle line.

I could not see the Confederates, and, as I had gone to the front expressly to see a battle, I pushed on, picking my way from protective tree to protective tree, until I was about forty yards from the battle line. The uproar was deafening. The bullets flew through the air thickly. Now our line would move forward a few yards, now fall back.

I stood behind a large oak tree and peeped around its trunk. I heard bullets "spat" into this tree, and I suddenly realized that I was under fire. My heart thumped wildly for a minute. Then my throat and mouth felt dry and queer. A dead sergeant lay at my feet, with a hole in his forehead just above his left eye. Out of this wound bits of brain oozed and slid on a bloody trail into his eye and thence over his check to the ground. I leaned over the body to feel of it. It was still warm. He couldn't have been dead for over five minutes. As I stopped over the dead man bullets swept past me, and I became angry at the danger I had foolishly gotten into.

|

| Wounded soldier uses a pitchfork to hobble along in the Wilderness. (Edwin Forbes | Library of Congress) |

I unbuckled the dead man's cartridge belt and strapped it around me, and then I picked up his rifle. I remember standing behind the large oak tree and dropping the ramrod into the rifle to see if it was loaded. It was not. So I loaded it, and before I fairly understood what had taken place I was in the rank of the battle line, which had surged back on the crest of a battle billow, bareheaded, and greatly excited, and blazing away at an indistinct, smoke and tree-obscured line of men clad in gray and slouch hatted.

As I cooled off in the heat of the battle fire, I found that I was on the Fifth Corps line, instead of on the Second Corps' line, where I wanted to be. I spoke to the men on either side of me, and they stared at me, a stranger, and briefly said that the regiment, the distinctive number of which I have long since forgotten, was near the left of the Fifth Corps, and that they had been fighting pretty steadily since about 10 o'clock in the morning, but with poor success, as the Confederates had driven them back a little.

The fire was rather hot and the men were falling pretty fast. Still, it was not anywhere near as bloody as I had expected a battle to be. As a grand, inspiring spectacle it was highly unsatisfactory, owing to the powder smoke obscuring the vision. At times we could not see the Confederate line, but that made no difference, we kept on firing just as though they were in full view. We gained ground at times, and then dead Confederates lay on the ground as thickly as dead Union soldiers had behind us. Then we would fall back, fighting stubbornly, but steadily giving ground, until the dead were all clad in blue.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

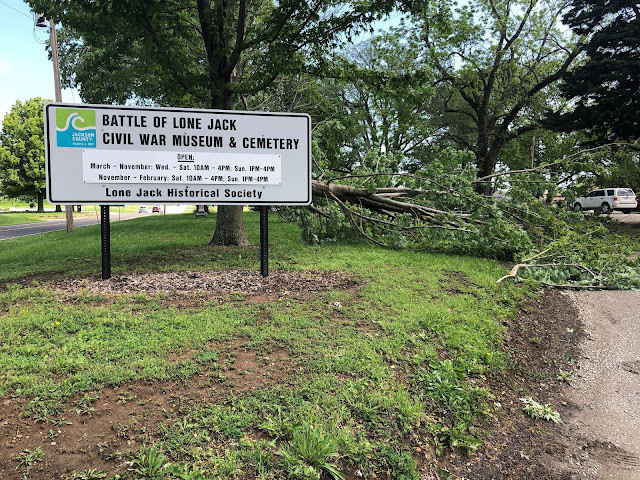

Former President Harry S. Truman, who lived in nearby Independence, Mo., dedicated the museum, housed in a circular stone and cement building, in 1963. "I tried to more than 42 years ago to erect a monument to the Lone Jack battle," Truman said on the 101st anniversary of the fighting. "They didn't think the battle was important then."

Former President Harry S. Truman, who lived in nearby Independence, Mo., dedicated the museum, housed in a circular stone and cement building, in 1963. "I tried to more than 42 years ago to erect a monument to the Lone Jack battle," Truman said on the 101st anniversary of the fighting. "They didn't think the battle was important then."