|

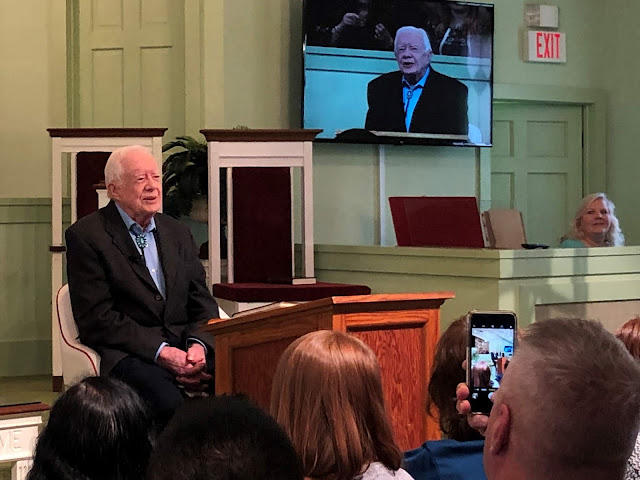

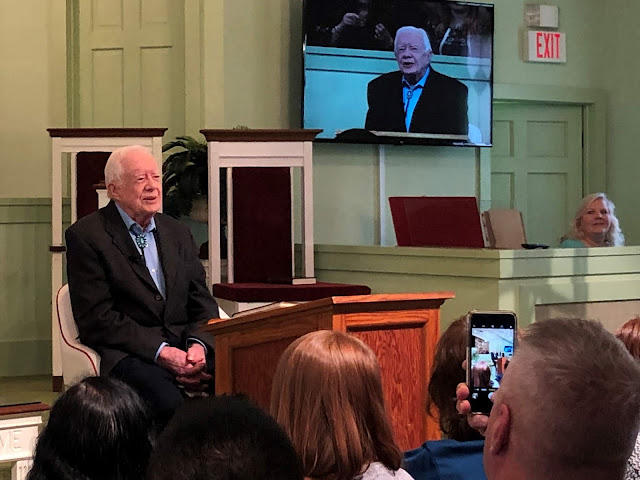

At Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Ga., Jimmy Carter delivers wisdom during his Sunday

school lesson while his niece, Jana (far right), daughter of Billy Carter, watches.

(CLICK ON ALL IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

|

| In the predawn darkness, George Williams greets visitors at Maranatha Baptist Church. |

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter

PLAINS, Ga. — At the ungodly hour of 5 a.m., faithful and faithless have gathered in the parking lot at

Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, population roughly 800 if you count the dogs and cats. The Sunday school lesson begins at 10 a.m. Church service starts an hour later. But most of the sleepy-eyed visitors on the outskirts of town aren’t here before dawn just for church.

|

A prized slip of numbered paper, a "ticket"

for admission to Carter's Sunday school lesson. |

The main attraction is 94-year-old native son Jimmy Carter, the 39th U.S. president. Twice a month, Carter – who still lives in Plains with former First Lady Rosalynn, his wife of 72 years – delivers a Sunday school lesson at Maranatha Baptist. Shortly after he lost the presidential election to Ronald Reagan in 1980, he began teaching at the church and attending Sunday service here.

Carter is renowned for his humanitarian and charitable efforts after his presidency. Most notably, he helps builds houses for Habitat for Humanity, and his Carter Center has helped monitor elections in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

In the predawn darkness, lifelong Plains resident George Williams, wearing a red Coke cap and windbreaker, greets visitors in vehicles at Maranatha’s parking lot entrance, a short distance from an oversized peanut with a toothy grin. "Where y'all from?" he asks as he hands a visitor a small slip of crinkled brown paper upon which a number is scrawled in felt-tip marker. "Park right up there by Jill. God bless y'all."

|

Before sunrise, Maranatha Baptist in Plains, Ga.,

is bathed in light. |

The lower your number, the better your chances of getting a seat for Carter’s lesson. On this damp morning in rural Georgia, another big event -- the Super Bowl in early evening in Atlanta, 160 miles north – may have thinned the crowd. Sometimes as many as 500 people attend Carter’s lesson. But there’s a little more than 350 Sunday. Only a handful will watch the former president on a monitor in the overflow room in the church instead of in person in the sanctuary.

Williams arrived at 2 a.m. The first visitor pulled in five minutes later. Some take their number and doze in their car. Others spring to life by gulping coffee. A small group engages in small talk near a grove of leafless trees behind Maranatha, a modest, red-brick building topped with a white steeple.

To some in Plains, Carter is "Mr. Jimmy." To others, he has been a hunting buddy. Most of all, locals proudly say, “He’s one of us.”

'He hasn't changed one bit'

|

Plains mayor Lynton Earl Godwin III, 75, is a longtime friend of Jimmy Carter.

"He hasn't changed one bit," he says. |

Longtime Plains mayor Lynton Earl Godwin III – almost everyone here calls him “Boze” -- arrives before sunrise. He surveys the parking lot with city councilwoman Jill Stuckey, who directs visitors to parking spaces with a wave of a large flashlight. She also serves as a de facto visitors’ guide, a role she assumed in 1998.

Although the crowd Sunday is “a little light,” Stuckey says, visitation has been “crazy busy” since news of Carter’s cancer diagnosis in 2015. (In summer 2018, Carter

said he was cancer-free.) “A lot of people have this on their bucket list,” she says. One Sunday about a decade ago, 48 countries were represented at the church in a single group from the University of Oxford in England. In late January, New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, a Democratic presidential candidate, and Rep. John Lewis, a civil rights icon, were welcomed.

Some visitors are especially devoted. The night before a Carter event – it’s more a pilgrimage, really -- two women from Missouri pitched a tent in a yard next to the church. They cooked their breakfast with the fire of a propane tank they brought.

Godwin has known Carter most of his life. “He has not forgot where he comes from,” the 75-year-old says. “He hasn’t changed one bit.”

To underscore the mayor’s point, Williams shows off cellphone images of himself hunting with Carter and laughing with the president at a softball game. He’s known Carter most of his life, too.

'A point of light in a veil of darkness'

|

David Kendall, 68, feeding his dog Luna, comes from a staunch Republican family. But he says he voted

for Jimmy Carter, a Democrat, twice for president. |

The first to arrive on Sunday morning is 68-year-old David Kendall, who pulled in at 2:05. He leans against his green Volkswagen van with a pop-up roof, tufts of gray hair peeking from under his green and white MAGA ballcap. No, not

that MAGA ballcap. His reads: “Make America Green Again.” A self-described East Tennessee farm boy, Kendall and his wife operate a small farm and lodge in western North Carolina. His residence is so deep in the woods, he says, that the location doesn’t even have a name.

On a six-week journey across the U.S., Kendall is traveling alone with his dog, Luna, a 9 ½-year-old mixed breed. He says he comes from a staunch Republican family, but he voted twice for Carter, a Democrat, for president.

|

Stephen Wilson, with his children Drew and Sarah,

admires Carter for his "moral authority." |

“He was given a plate of spoiled food,” Kendall says of Carter’s presidency. He ticks off the challenges the president faced during his term from 1976-80, including an oil crisis in 1979: “I think he did the best he could with what he had.”

Kendall says he admires the former president most of all for his outstanding character, a key reason many of the morning’s visitors traveled to hear the former president. “Carter is a point of light in a veil of darkness,” he says, contrasting him with present-day politicians.

At least a dozen states are represented on license plates on vehicles near Kendall’s VW. Lou Fuller, from Chattanooga, Tenn., arrived with her friend, Addie, at about 5 a.m. She recalls hearing Carter, Georgia governor from 1971-75, speak at a PTA meeting during his successful run for that office.

“Who has this kind of access for a former president?” Fuller says when asked why she’s here.

Stephen Wilson, a 41-year-old lawyer from Carrollton, Ga., drove 2 ½ hours with his wife and three young children to hear Carter. An ardent Democrat, he says he admires the former president for his “moral authority.”

“Building those houses at age 94, working with troubled democracies. He’s a hands-on person,” says Wilson, dressed in a suit and sporting a red, white and blue bowtie. Carter, he adds, is a “supporter of our endangered values.”

|

| Susan and Mark Tons of St. Louis arrived at about 5 a.m. for Jimmy Carter's lesson. |

Fresh off a cruise to Spain and England, retired couple Mark, 66, and Susan Tons, 63, also arrived about 5 a.m. From St. Louis, they describe themselves as non-religious. “As a president, he was not good,” Mark says between sips of coffee, “but as a human being he’s the best.”

A visitor from Florida praises the simplicity of the event: “They could have citified this,” she says, “made it a high-falutin, fancy place. But they haven’t. It’s the same as it always has been. Good people here."

'Miss Jan': Part drill sergeant, part comedian

|

Jan Williams, fondly called "Miss Jan," gives detailed instructions to church visitors. If you want a photo

with President Carter, she tells them, you must stay for the 11 a.m. church service. |

At about 7:30 a.m., longtime church member Jan Williams, George’s wife, gathers visitors for pre-service instructions. Some are dressed in their Sunday finest, others wear informal attire. There is no dress code at Maranatha Baptist, a blessing for an unshaven visitor wearing black Nike sweatpants and a scroungy, black Puma sweatshirt.

|

At about 7:45 a.m., visitors form in line for Carter's

Sunday school lesson at Maranatha Baptist Church. |

Part drill sergeant and part comedian, Jan goes over the well-established church rules: No shaking Carter’s hand; no conversation with him; no autographs; and if you want a photo with the president, you must stay for the church service following his lesson. And, of course, no smoking in church. “If you smoke,” Williams says, “this may be the best day to quit.”

As Williams issues commands, a bomb-sniffing dog, part of Carter’s Secret Service escort, ventures around the church’s exterior. “This is the safest place in the world to go to church,” she says emphatically.

At about 7:45, Williams orders visitors into line by their “ticket” numbers. She rejoices that the weather is mild. “Thank God,” Williams tells those in line, “God doesn’t let it rain here very much. One time we had to break out the hair dryers because folks got sloppin’ wet.”

At the church entrance, visitors unload their cellphones and anything else in their pockets or purses at a small table in front of two Secret Service agents. Two other agents wave a metal detecting wand over visitors and members before they are admitted. In the entryway, Mayor Godwin hands out church service bulletins.

In the sanctuary, there are three sections of pews, 13 rows in each section. Folding chairs add to capacity of the church, which only has about 30 active members. The walls and carpet are shades of key-lime green. Light streams through 10 stained-glass windows. Newly installed large-screen monitors flank the altar. With military-like precision, “Miss Jan” helps direct traffic.

|

The Secret Service lays down the law

when Carter attends Maranatha Baptist Church. |

Before the lesson, Jana Carter, daughter of Carter’s brother, Billy, talks about her famous uncle. “He’s just a hometown boy to us,” she says, “who happens to have been the 39th president of the United States.” Like Williams, she has the genes of a comedian in her DNA and enjoys interacting with visitors. She briefly puts on her Chamber of Commerce hat, offering advice on where to eat after church or buy peanut butter ice cream in Plains.

Jana goes over ground rules, too. The president will ask the people in each section where they’re from. Tell him in a loud voice, she says, because he’s hard of hearing. Jana practices with each group.

“Poland,” says a man.

“Canada,” says another.

When the president enters the sanctuary, Jana instructs, say “Good Morning” in unison.

Loudly.

Jill Stuckey provides the most important instructions of all: how to get a picture taken with Mr. and Mrs. Carter, 91, after the service concludes. Have your phone ready. Give it to Stuckey, who will quickly take the photo. Don’t dawdle. The aim is to get the photography wrapped up in 15 minutes. Clearly, this isn’t her first photo rodeo.

Carter teaches lessons from the Bible, often sprinkled with thoughts on current events. While not out of bounds, political topics are rarely discussed. Besides the twice-monthly lessons, he has touched the church in other ways. “Mr. Jimmy” made the wooden offering plates – his initials are on the bottom – and the cross behind the altar. He also has made repairs in the church and cut bushes and hedges. “He was our handyman,” Stuckey says. Mrs. Carter has often pitched in for church work, too. She even has cleaned the restrooms.

|

Jimmy Carter has touched Maranatha Baptist in many ways. He

even made the offering plates. His initials "J.C." appear at right.

(CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE.) |

Before the president’s arrival, Cheryl and Joe Bistayi talk with another visitor in a pew near the front. The couple is from Novi, Mich. Cheryl, who grew up in Chicago, laughs when she tells about what her father said decades ago about the 39th president. “Jimmy Carter is a good and decent man,” he told her, “and you can’t have a guy like that run the government.”

Soon, stern-looking Secret Service agents stir on each side of the sanctuary.

At 9:57 a.m., a man wearing a black suit, light blue shirt and a turquoise and black bolo tie slowly walks into the room.

“Good morning, everybody” President Carter says.

“Good morning!” shout the worshipers.

Loudly.

The lesson begins.

|

The former first couple -- Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter -- with blogger John Banks. The Carters

pose for photos with visitors at Maranatha Baptist after the 11 a.m. service. |

Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.