|

| A daguerreotype of Nancy Campbell. (National Park Service collection) |

During visits to Sharpsburg, Md., more than a decade ago, I was fortunate to spend time with Earl Roulette and his wife, Annabelle, at their ranch house on Main Street, near Robert E. Lee's headquarters site during the Battle of Antietam.

While Annabelle rocked in her chair in the living room, Earl and I chatted about the Civil War in a small backroom. Earl especially enjoyed showing off Civil War artifacts he had found while farming in the area for more than 50 years. His great-grandfather's farm, which bordered Bloody Lane, was scene of horrific fighting during the battle.

During one visit, Earl reached into a small box for a photo of a woman named Nancy Campbell.

My friend Richard Clem, a lifelong resident of Washington County (Md.), picks up her story.

By Richard E. Clem

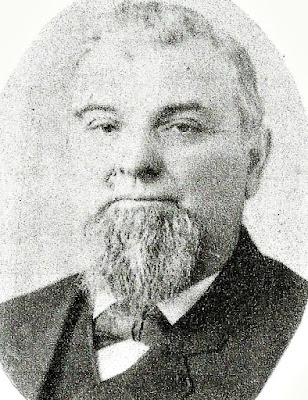

Maryland's 1860 census for Washington County lists a “Nancy Campbell” as a servant living with the Roulette family in the Sharpsburg District. History reveals little about this small, black slave. The first the author heard the name mentioned was in Sharpsburg while visiting dear friends Earl and Annabelle Roulette. In his normal high-pitched voice, Earl handed me an old daguerreotype in its small, protective case and with pride explained: “This is Nancy Campbell; she was my great grandfather’s house servant.” Earl’s ancestor was William Roulette, whose farm suffered great damage on Sept. 17, 1862, during the Battle of Antietam – the bloodiest day of the Civil War. From the very moment I examined Nancy’s image, I was determined to cast light on the life of this virtually unknown woman.

The name “Nancy Campbell” first appears on a Certificate of Freedom recorded in the Washington County Court House in Hagerstown, Md.:

At the request of Nancy Campbell, the following deed was recorded June 14, 1859, by Andrew Miller of Washington County, Maryland. I do hear-by set free my Negro slave, Nancy Campbell, her freedom to commence from the year eighteen hundred and fifty nine.

The document was witnessed and signed by Justice of the Peace Thomas Curtis McLaughlin and Andrew Miller – Campbell’s former owner or, as referred to in the South, her “master.”

Andrew B. Miller was born March 24, 1826, in Washington County, Md. At an unknown date, he purchased a 50-acre farm in Tilghmanton, where his wife, Heaster Ann (Smith) Miller, gave birth to at least three children. Tilghmanton is a small town (population today, 465) on the Sharpsburg Pike, 8.5 miles south of Hagerstown and about the same distance from Sharpsburg.

When Andrew’s father, Peter Miller, passed away, his will provided his son with a servant named “Nancy Campbell,” described as: “One Colored Woman, 5 feet 1 ½ inches high, worth $250.00.” With this appraised value, Miss Nancy was worth as much as a good horse.

It was against the law to teach a slave how to read or write, so no record exists to state where Campbell was born or who her parents were. Even the date she was acquired by the Peter Miller family is unknown. Along with being a house servant, Nancy would have also taken care of the younger children as a “nanny.” When not occupied with the kids, she would have been required to do cooking as well as other household chores and perhaps tend to the vegetable garden.

Freedom and New Home

Looking to take life easier, Andrew Miller sold his Tilghmanton property in 1859, just prior to outbreak of the Civil War. Now with no need for a slave, the retiring farmer decided to grant Miss Campbell her freedom. But without a home or education and no way to support herself, what would happen to the 46-year-old black servant trying to survive in a world among white strangers?

Less than one year after being freed, she not only had a new home, but would receive wages for her labor. It is believed this freed slave first met the Roulettes through William’s marriage (March 4, 1847) to Margaret Ann Miller. In April 1853, Mr. Roulette bought the farm of his wife’s father, John Miller. John’s brother, Peter Miller, Nancy Campbell’s first owner, was an uncle to Mrs. Roulette. So it's very possible Campbell knew the Roulettes before she went to live with them.

When Miss Campbell began working for William and Margaret Ann, they were the parents of five children. Their need for a good, experienced nanny was great. Although Mr. Roulette owned no slaves, he employed and paid for the services of Nancy and a 15-year-old boy named Robert Simon.

The new nanny occupied a small room over the Roulette’s kitchen, while Robert was employed as an “African American field hand, resided somewhere on the property.” Evidence clearly shows Roulette’s springhouse once had a third floor; some historians speculate this upper room was occupied by Simon. Soon after Nancy’s arrival, Margaret Ann gave birth (Feb. 23, 1860) to her third daughter, Carrie May.

In the late 19th century, William Roulette and his close neighbor, Samuel Mumma, were considered the most prosperous farmers in the Sharpsburg District, raising mostly corn, oats and barley in their fine limestone soil. And then the War Between the States came to Maryland! According to William’s History of Washington County, the day before the Battle of Antietam, William Roulette “took his family six miles north to the Manor Church where they were sheltered by Elder Daniel Wolf, a minister of that church.” Campbell and Simon probably joined the Roulette family at the Manor Church. The Mummas also evacuated their farm and sought protection at the Manor house of worship.

While living at Tilghmanton, Miss Campbell, a member of the mostly white Manor congregation, probably heard Reverend Daniel Wolf’s sermons against the evils of slavery. If you owned a slave or slaves, you were not allowed to be a member of this church. Locals called this sanctuary the Manor Dunker Church or “Tunkard” in German. Built in 1830, this meeting house just east of Tilghmanton was the mother church of the now-famous Dunker Church on the Antietam battlefield. (Services are still held every Sunday in the old limestone structure that now has a large, brick addition and is known as the Manor Church of the Brethren.)

War Hits Home

PANORAMA: William Roulette farmhouse and barn (pan to the right).

PANORAMA: Roulette's farmhouse and barn were used as makeshift hospitals

during and after the battle. (Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

Early on the misty morning of Sept. 17, 1862, General George B. McClellan, commander Army of the Potomac, launched a series of assaults on General Robert E. Lee’s formidable left flank. When these attempts failed to dislodge General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s veterans from the West Woods, another attack on the Rebel center was made at 10 a.m. by General William H. French’s division. The 5,000 mostly untested Yankees marched blindly toward a Southern line concealed in a sunken farm lane referred to as Hog Trough Road. Directly in the path of the Federal advance stood the Roulette farm.

With his family safe in the Manor Church, William Roulette returned to protect his farm, spending most of the day of the battle in the cellar but at least once sticking his head out and cheering on the Union infantry. (Some historians claim the Roulette family stayed in their cellar day of the battle, too.) Following the firestorm, one Federal soldier remembered, “Around the surgeon’s table in the Roulette barn amputated arms and legs were piled several feet deep.” Another witness later recalled the damage to Roulette’s property, “The buildings were struck by shot and shell of which they still bear the marks. One shell pierced the southern end of the dwelling, went up through the parlor ceiling and was found in the attic.” (The Samuel Mumma family, however, lost far more during the battle -- their house and barn were burned and destroyed, leaving only smoldering ruins.)

The Roulette family must have been devastated and disheartened to see their home and barn converted into a field hospital filled with bloodied, dead and wounded soldiers. Just south of Roulette’s lane, Confederate dead and wounded were stacked in the sunken road, now better known as Bloody Lane. One report stated at least 700 dead were buried on the Roulette farm. Crops about to be harvested were ruined and the farmer's fields were strewn with canteens, blankets, guns, knapsacks and countless other implements of war. According to a damage claim filed by Roulette, his house was “stripped during the battle of furnishings and floors were left covered with blood and dirt from being used as a hospital.” The Federal government compensated Roulette $371 toward an estimated claim totaling $3,500.

Like most residents of the Sharpsburg area, Campbell, Simon and the Roulettes pitched in to bring comfort and relief to thousands of bloodied humanity. Adding grief to misery, on Oct. 21, 1862, just 31 days after the battle, the Roulettes' 20-month-old daughter, Carrie May, died from typhoid fever. The toddler may have contracted the fatal disease from exposure to wounded soldiers. Nancy Campbell, Carrie May’s nanny from birth, surely suffered from the death of the little girl.

Final Homecoming

In 1887, William Roulette turned over the farm to his youngest son, Benjamin Franklin Roulette, and the 63-year-old farmer moved into a smaller house in Sharpsburg. By this time, Nancy was getting up in years herself and only able to do “light” work, but the caring Ben Roulette let her stay on at the old homestead. William Roulette died Feb. 27, 1901. Margaret Ann had passed away 18 years earlier, on Feb. 19, 1883. Both are buried in Mountain View Cemetery on the eastern edge of Sharpsburg.

There is no doubt Miss Campbell was respected and paid decently for her household labor. At an unknown date, she had her picture taken, perhaps by a professional Sharpsburg photographer. The dress she wore in the image appears to be of fine material. (In a velvet-lined case, the photograph is now in the collection of the National Park Service at Antietam, courtesy of Earl Roulette.)

Miss Nancy was set free “forever” on Jan. 5, 1892, at age 79. On Jan. 20, 1885, seven years before her death, she had recorded a last will and testament with the Register of Wills in the Washington County Court House. It was rare for a slave, freed or in bondage, to have a will or a significant amount of money.

Combining cash in the bank with “cash in the house,” her estate value totaled $867.04, not including Nancy’s personal property. The will gives testimony to where this one-time slave placed her trust: “I give and bequeath to the Manor Church of the Tunker denomination to which I belong in Washington County, Maryland, the sum of Fifty Dollars.” The Afro-American Methodist Church in Sharpsburg also received $20 along with her personal Bible. Still standing and recently restored, this one-room log church was built in 1866 by Rev. J. R. Tolson for slaves and their children freed after the Civil War. Campbell attended Tolson Chapel while staying with the Roulettes, and the gift from her will is another example of the value she placed on spiritual guidance and worship.

Nancy also remembered with fondness her former master: “I give and bequeath to Andrew Miller, my chest, my trunk and my stand.” The will also provided $25 each to three of Miller’s children, Hamilton, Thomas and Susan. Heaster Ann Miller passed away March 11, 1899, and her husband, Andrew, was placed at her side in the Manor Church Cemetery on Dec. 8, 1910.

The will also reveals one of Roulette’s daughters was highly thought of by her nanny. “And unto Rebecca Roulette, daughter of William Roulette," the document reads, "I give the sum of One Hundred Dollars together with all my personal effects.” When Nancy went to live with the Roulettes, Susan Rebecca was only 5. It is evident the bond of affection and love between these two individuals was strong.

As executor of the Campbell estate, Ben Roulette was responsible for paying the deceased’s burial expenses. For a coffin of “rough lumber,” J. L. Highberger, a Sharpsburg blacksmith, was paid $46. Samuel Line was paid $2.50 for hand-digging the grave. A member of the Manor Church congregation, Nancy was entitled to burial in church cemetery. Unknown for years, her tombstone remained face down. It was recently accidentally discovered and set erect by the cemetery caretaker. The stone is inscribed:

NANCY CAMPBELL

BORN

OCT. 15, 1813

DIED

JAN. 5, 1892

AGED

78 Ys 2 Mo & 20 Ds

At the bottom of the well-worn stone are these words from Scripture: “Blessed Are The Dead Which Die In The Lord.” Revelation 14:13.

Records do not exist as to who furnished the gravestone or why the last name is spelled “Camel.” The same spelling, however, is found on several other legal documents for Nancy. But because she had no known relatives, perhaps it is understandable why the stone engraver inscribed it as he did. Even Miss Campbell, not being able to write, wouldn’t have known the correct spelling of her last name, which also explains why she signed her last will and testament with an “X.”

The life story of this humble yet “blessed” servant is dedicated to the lasting memory of Earl and Annabelle Roulette. The author will always cherish their warm, Christian friendship and hospitality given on a fall afternoon in Sharpsburg.

SOURCES:

|

| Richard E. Clem |

Maryland's 1860 census for Washington County lists a “Nancy Campbell” as a servant living with the Roulette family in the Sharpsburg District. History reveals little about this small, black slave. The first the author heard the name mentioned was in Sharpsburg while visiting dear friends Earl and Annabelle Roulette. In his normal high-pitched voice, Earl handed me an old daguerreotype in its small, protective case and with pride explained: “This is Nancy Campbell; she was my great grandfather’s house servant.” Earl’s ancestor was William Roulette, whose farm suffered great damage on Sept. 17, 1862, during the Battle of Antietam – the bloodiest day of the Civil War. From the very moment I examined Nancy’s image, I was determined to cast light on the life of this virtually unknown woman.

The name “Nancy Campbell” first appears on a Certificate of Freedom recorded in the Washington County Court House in Hagerstown, Md.:

|

| Nancy Campbell toiled for William Roulette, whose farm was scene of terrible fighting at the Battle of Antietam on Sept. 17, 1862. |

The document was witnessed and signed by Justice of the Peace Thomas Curtis McLaughlin and Andrew Miller – Campbell’s former owner or, as referred to in the South, her “master.”

Andrew B. Miller was born March 24, 1826, in Washington County, Md. At an unknown date, he purchased a 50-acre farm in Tilghmanton, where his wife, Heaster Ann (Smith) Miller, gave birth to at least three children. Tilghmanton is a small town (population today, 465) on the Sharpsburg Pike, 8.5 miles south of Hagerstown and about the same distance from Sharpsburg.

When Andrew’s father, Peter Miller, passed away, his will provided his son with a servant named “Nancy Campbell,” described as: “One Colored Woman, 5 feet 1 ½ inches high, worth $250.00.” With this appraised value, Miss Nancy was worth as much as a good horse.

It was against the law to teach a slave how to read or write, so no record exists to state where Campbell was born or who her parents were. Even the date she was acquired by the Peter Miller family is unknown. Along with being a house servant, Nancy would have also taken care of the younger children as a “nanny.” When not occupied with the kids, she would have been required to do cooking as well as other household chores and perhaps tend to the vegetable garden.

Freedom and New Home

|

| William Roulette's springhouse, where the farmer's African-American field hand, Robert Simon, is believed to have lived. (Photo: Richard E. Clem) |

Less than one year after being freed, she not only had a new home, but would receive wages for her labor. It is believed this freed slave first met the Roulettes through William’s marriage (March 4, 1847) to Margaret Ann Miller. In April 1853, Mr. Roulette bought the farm of his wife’s father, John Miller. John’s brother, Peter Miller, Nancy Campbell’s first owner, was an uncle to Mrs. Roulette. So it's very possible Campbell knew the Roulettes before she went to live with them.

When Miss Campbell began working for William and Margaret Ann, they were the parents of five children. Their need for a good, experienced nanny was great. Although Mr. Roulette owned no slaves, he employed and paid for the services of Nancy and a 15-year-old boy named Robert Simon.

The new nanny occupied a small room over the Roulette’s kitchen, while Robert was employed as an “African American field hand, resided somewhere on the property.” Evidence clearly shows Roulette’s springhouse once had a third floor; some historians speculate this upper room was occupied by Simon. Soon after Nancy’s arrival, Margaret Ann gave birth (Feb. 23, 1860) to her third daughter, Carrie May.

|

| Manor Church, where the Roulette family is believed to have been sheltered during the Battle of Antietam. Nancy Campbell attended services here. (Photo: Richard E. Clem) |

While living at Tilghmanton, Miss Campbell, a member of the mostly white Manor congregation, probably heard Reverend Daniel Wolf’s sermons against the evils of slavery. If you owned a slave or slaves, you were not allowed to be a member of this church. Locals called this sanctuary the Manor Dunker Church or “Tunkard” in German. Built in 1830, this meeting house just east of Tilghmanton was the mother church of the now-famous Dunker Church on the Antietam battlefield. (Services are still held every Sunday in the old limestone structure that now has a large, brick addition and is known as the Manor Church of the Brethren.)

War Hits Home

during and after the battle. (Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

Early on the misty morning of Sept. 17, 1862, General George B. McClellan, commander Army of the Potomac, launched a series of assaults on General Robert E. Lee’s formidable left flank. When these attempts failed to dislodge General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s veterans from the West Woods, another attack on the Rebel center was made at 10 a.m. by General William H. French’s division. The 5,000 mostly untested Yankees marched blindly toward a Southern line concealed in a sunken farm lane referred to as Hog Trough Road. Directly in the path of the Federal advance stood the Roulette farm.

|

| While the Battle of Antietam raged, William Roulette found shelter in his cellar. |

The Roulette family must have been devastated and disheartened to see their home and barn converted into a field hospital filled with bloodied, dead and wounded soldiers. Just south of Roulette’s lane, Confederate dead and wounded were stacked in the sunken road, now better known as Bloody Lane. One report stated at least 700 dead were buried on the Roulette farm. Crops about to be harvested were ruined and the farmer's fields were strewn with canteens, blankets, guns, knapsacks and countless other implements of war. According to a damage claim filed by Roulette, his house was “stripped during the battle of furnishings and floors were left covered with blood and dirt from being used as a hospital.” The Federal government compensated Roulette $371 toward an estimated claim totaling $3,500.

Like most residents of the Sharpsburg area, Campbell, Simon and the Roulettes pitched in to bring comfort and relief to thousands of bloodied humanity. Adding grief to misery, on Oct. 21, 1862, just 31 days after the battle, the Roulettes' 20-month-old daughter, Carrie May, died from typhoid fever. The toddler may have contracted the fatal disease from exposure to wounded soldiers. Nancy Campbell, Carrie May’s nanny from birth, surely suffered from the death of the little girl.

Final Homecoming

|

| Nancy Campbell attended the one-room Tolson Chapel on High Street in Sharpburg, Md. (Photo: Richard E. Clem) |

There is no doubt Miss Campbell was respected and paid decently for her household labor. At an unknown date, she had her picture taken, perhaps by a professional Sharpsburg photographer. The dress she wore in the image appears to be of fine material. (In a velvet-lined case, the photograph is now in the collection of the National Park Service at Antietam, courtesy of Earl Roulette.)

Miss Nancy was set free “forever” on Jan. 5, 1892, at age 79. On Jan. 20, 1885, seven years before her death, she had recorded a last will and testament with the Register of Wills in the Washington County Court House. It was rare for a slave, freed or in bondage, to have a will or a significant amount of money.

Combining cash in the bank with “cash in the house,” her estate value totaled $867.04, not including Nancy’s personal property. The will gives testimony to where this one-time slave placed her trust: “I give and bequeath to the Manor Church of the Tunker denomination to which I belong in Washington County, Maryland, the sum of Fifty Dollars.” The Afro-American Methodist Church in Sharpsburg also received $20 along with her personal Bible. Still standing and recently restored, this one-room log church was built in 1866 by Rev. J. R. Tolson for slaves and their children freed after the Civil War. Campbell attended Tolson Chapel while staying with the Roulettes, and the gift from her will is another example of the value she placed on spiritual guidance and worship.

Nancy also remembered with fondness her former master: “I give and bequeath to Andrew Miller, my chest, my trunk and my stand.” The will also provided $25 each to three of Miller’s children, Hamilton, Thomas and Susan. Heaster Ann Miller passed away March 11, 1899, and her husband, Andrew, was placed at her side in the Manor Church Cemetery on Dec. 8, 1910.

The will also reveals one of Roulette’s daughters was highly thought of by her nanny. “And unto Rebecca Roulette, daughter of William Roulette," the document reads, "I give the sum of One Hundred Dollars together with all my personal effects.” When Nancy went to live with the Roulettes, Susan Rebecca was only 5. It is evident the bond of affection and love between these two individuals was strong.

|

| Nancy Campbell's gravestone in Manor Church Cemetery. Her last name is misspelled "Camel." (Photo: Richard E. Clem) |

NANCY CAMPBELL

BORN

OCT. 15, 1813

DIED

JAN. 5, 1892

AGED

78 Ys 2 Mo & 20 Ds

At the bottom of the well-worn stone are these words from Scripture: “Blessed Are The Dead Which Die In The Lord.” Revelation 14:13.

|

| Annabelle and Earl Roulette. |

The life story of this humble yet “blessed” servant is dedicated to the lasting memory of Earl and Annabelle Roulette. The author will always cherish their warm, Christian friendship and hospitality given on a fall afternoon in Sharpsburg.

Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES:

- Bailey, Ronald H., The Bloodiest Day: The Battle of Antietam, Time-Life Books Inc., Alexander, Virginia, 1984

- Ernst, Kathleen A., Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians In The Antietam Campaign, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pa., 1999

- Frassanito, William A., Antietam: The Photographic Legacy of America’s Bloodiest Day, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1978

- Morrow, Dale W., Washington County, Maryland Cemetery Records – Volume 1, Family Line Publications, Westminster, Md., 1992

- Maurice, Henry J., History of the Church of the Brethren in Maryland, Brethren Publishing House, Elgin, Ill., 1936

- Murfin, James V., The Gleam of Bayonets, Thomas Yoseloff Publisher, Cranbury, N.J., 1968

- Reilly, Oliver T., The Battlefield of Antietam, Hagerstown Bookbinding & Printing Co., Hagerstown, Md.,1906

- Schildt, John W., Antietam Hospitals, Antietam Publications, Chewsville, Md., 1987

- Sears, Stephen W., Landscape Turned Red, Ticknor & Fields, New Haven and New York, 1983

- Williams, Thomas J. C., History of Washington County, Maryland, Regional Publishing Company, Baltimore, Md., 1968.

- www.findagrave.com.

This article truly humanizes the full story of Antietam. I am eager and hopefully shall be able to visit the area again soon. Previous visit was back in '93.

ReplyDeleteAre you familiar with Red Hill cemetery previously known as (1840) Mount Pleasant it is a cemetery & school in the church in keddysville Maryland

ReplyDeleteFascinating account. I can't wait to get back to Sharpsburg and area to find the places mentioned.

ReplyDelete