|

| An illustration in Harper's Weekly shows the execution by firing squad of a Union deserter in 1861. |

Adapted from my book, Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers. E-mail me here for information on how to purchase an autographed copy.

Adapted from my book, Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers. E-mail me here for information on how to purchase an autographed copy.

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter

About 3 p.m. on Sunday, April 17, 1864, all the troops in the 6th Connecticut and three other regiments assembled in a field by a causeway near their camp in Hilton Head, South Carolina, for a gruesome spectacle: the execution of two of their own. The condemned men were 6th Connecticut Privates Henry Stark of Danbury and Henry Schumaker of Norwalk -- deserters whose “

skill and perseverance might have won them honor if rightly applied.” Draftees and immigrants from Germany, the men had joined the regiment six months earlier.

Although some conscripts and draftees “manifested a disposition to do their duty, and did make very good soldiers,” according to an officer in the regiment, most of the 200 who swelled the ranks of the three-year regiment were not trusted by the volunteers. “Their advent was not hailed with much pleasure or satisfaction by the old regiment, as they claimed that ‘forced men’ would not fight and could not be trusted in case of emergency,” wrote Charles Cadwell, a sergeant in Company K from New Haven.

Along with another German immigrant and draftee, Private Gustave Hoofan of Danbury, Stark and Schumaker deserted while on picket duty sometime in February. Recaptured, they were placed in close confinement but escaped twice more. After the second escape, the three men were captured in Ossanabaw Sound, near Savannah, Georgia, about 40 miles from Hilton Head, and placed in the provost guard house. On March 4, 1864, they were court-martialed and sentenced to death by firing squad.

But before the sentences could be carried out, the three “very bold, ingenious” Germans, who had been chained hand and foot to a post inside of the provost quarters, somehow escaped again, using a boat near a pier to make their way to freedom. After their vessel ran aground near Warsaw Sound in Georgia, they were recaptured by soldiers aboard a picket boat from the gunboat

Patapsco and placed under tight guard upon their return to Hilton Head.

|

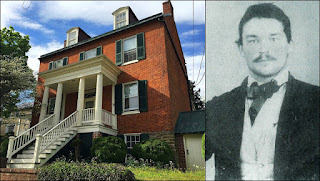

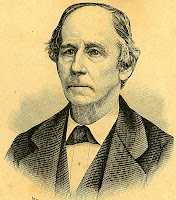

| 6th Connecticut Colonel Redfield Duryee |

For Schumaker and Stark, the end was near. An exceptionally lucky Hoofan, however, made another great escape thanks to a most fortuitous circumstance: a clerical error. The judge advocate misspelled his last name “Hoffman” on the death warrant, leading a by-the-book Colonel Redfield Duryee of the 6th Connecticut to protest the sentence of the private, who was then ordered to be released and returned to duty in his regiment.

“The man was more than pleased at this announcement,” recalled Cadwell about Hoofan, “but the Judge Advocate, a lieutenant of the Eighty-fifth Pennsylvania regiment, was severely censured in general orders for his inexcusable carelessness and fatal error.”

The day before the sentence was carried out, Duryee ordered that all fatigue work be suspended on the day of execution and that every officer and man not on the sick list or other duty be present for the macabre event. “Every soldier who could walk was ordered to go,” 6th Connecticut Pvt. Hugh Ives of Hoofan’s Company B wrote to his mother on the afternoon of the executions.

Advised of their fate by the provost marshal, Schumaker and Stark “seemed stolid and indifferent at first, but upon reflection they gave way to their feelings and desired to have a priest sent to them” because each was Roman Catholic, Cadwell wrote. “… It was for a long time difficult to convince them that their case was hopeless, but [the priest’s] arguments finally forced conviction, and, after hearing their confession twice, he performed all the rites of the Church that were practicable.”

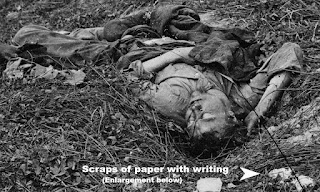

Taken from their cells about 2 p.m., the men rode in army wagons upon the coffins in which they were to be buried. As funeral music played, two ranks of drum corps, the regimental chaplain, two surgeons, a reverend from the U.S. Christian Commission and a 24-man firing squad of soldiers from the 6th Connecticut slowly made their way to the execution site. The condemned were driven around their comrades, who formed in a three-sided square, so all the assembled soldiers could get a good look at what happens to men who desert the Union army.

“They maintained a calm demeanor to all,” Cadwell noted, “except as they passed our regiment they took off their caps several times to their old comrades.”

After they reached the end of the square, the soldiers were assisted from the wagons and their coffins were placed on the ground. The provost marshal read the charges and the sentence for the condemned. A priest then delivered a short prayer before he heard their confessions, forgave and pardoned them, sprinkled holy water on the soldiers and bade them goodbye.

After they were blindfolded and their hands were tied behind them, the Germans were made to kneel upon their coffins, facing their regiment. Commanded by 6th Connecticut Captain John King of Hartford, the executioners went into position five or six paces from the men, and when Captain Edwin Babcock of the U.S. Colored Troops gave the signal with his sword, they fired into Schumaker and Stark, riddling them with bullets and killing them.

“Both culprits met their death with indifference,” the

Hartford Daily Courant reported on April 28, 11 days after the executions, “and were killed by the first volley.”

“One fell forward the other backward,” wrote Ives, who along with the rest of the regiment marched passed the dead men en route back to camp before each was buried. “There is another one to be shot tomorrow. He belongs to our regiment.”

On April 30, a heart-rending letter Schumaker had written to his father in Germany the morning of his death was published in the

Hartford Daily Courant. Translated from German, it read:

Dear Father

When this letter reaches you, I shall not be longer living. I did very wrong years ago to leave you. Farewell, my dear parents, and you, dear sisters, whom I shall meet again in Heaven. Do not grieve me much; and you too, dear mother, my fate is just, I have deserved it, and sacrificed my life in this land. A thousand times farewell and hold me close in memory.

Your Unlucky Son

After the war, the remains of deserters Schumaker and Stark were disinterred and re-buried side-by-side in the national cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina, among the remains of more than 9,000 other Yankee soldiers.

Gustave Hoofan deserted again on November 11, 1864. His fate is unknown.

|

Deserters Henry Schumaker and Henry Stark are buried side-by-side in

Beaufort (S.C.) National Cemetery. (Photo: Judy Birchenough) |

Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

NOTES AND SOURCES

-- There are several variations of Gustave Hoofan’s name, including Hoffan and Hofen.

-- Cadwell, Charles K.,

The Old Sixth Regiment, Its War Record, New Haven, Conn.: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1875

-- 6th Connecticut Pvt. Hugh Ives letter to his sister, April 17, 1864, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Conn.

5. SEND MY BIBLE HOME TO ALABAMA: On July 4, 1864, Confederate Private Lewis Branscomb was killed by a Union sharpshooter in the front yard of a house on Washington Street in Harpers Ferry, Va., (now West Virginia). The owner of the house recovered Lewis' Bible, and nearly three months after the war had ended, she sent a letter to his mother in Alabama.

5. SEND MY BIBLE HOME TO ALABAMA: On July 4, 1864, Confederate Private Lewis Branscomb was killed by a Union sharpshooter in the front yard of a house on Washington Street in Harpers Ferry, Va., (now West Virginia). The owner of the house recovered Lewis' Bible, and nearly three months after the war had ended, she sent a letter to his mother in Alabama. 4. DOCTOR'S REMARKABLE ANTIETAM LETTER: Friend of the blog Dan Masters shared with me a fabulous letter written on Sept. 29, 1862, 12 days after Antietam, by Dr. Augustin Biggs, who experienced first hand the battle and its terrible, bloody aftermath.

4. DOCTOR'S REMARKABLE ANTIETAM LETTER: Friend of the blog Dan Masters shared with me a fabulous letter written on Sept. 29, 1862, 12 days after Antietam, by Dr. Augustin Biggs, who experienced first hand the battle and its terrible, bloody aftermath.