Thursday, July 29, 2021

Thursday, July 22, 2021

What lies beneath? A Vanderbilt team explores Shy's Hill

|

| The ground-penetrating radar provides an "image" of the subsurface like this one, held by Vanderbilt research analyst Natalie Robbins. |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

SOURCE

- Nashville Tennesseean, Dec. 13, 1959.

Monday, July 19, 2021

Rebels' 'vandalism': Defacement of Andrew Jackson monument

|

| A cropped version of a Harper's Weekly illustration from July 5, 1862, of a park monument to Andrew Jackson in Memphis, Tenn. It was defaced by Confederate sympathizers. (Archive.org.) |

|

| This Andrew Jackson monument in Lafayette Square, opposite the White House, was defaced in 2020. (Wikipedia | AgnosticPreachersKid) |

In the center of Union-occupied Memphis, Tenn., in June 1862 was a beautiful park filled with trees, flowers, shrubbery, and "benches for the accommodation of loungers of both sexes." Surrounded by an iron railing, the public square -- lighted by gas at night -- was a premier gathering spot. Authorities aimed to keep it that way -- dogs were discouraged, and anyone who meddled with the shrubbery risked a $10 fine, a significant sum. (You can still visit Court Square, where scenes from The Firm, the 1993 movie starring Tom Cruise and Gene Hackman, were filmed.)

In the park's northwestern section, surrounded by a circular iron fence and "ornamented by carefully trained shrubbery," rested a large, marble bust of Jackson atop a tall pedestal. (The former president was a co-founder of Memphis.) "Honor and gratitude to those who have filled the measure of their country’s glory," read an inscription in the pedestal's south side. On the north side appeared these words:THE FEDERAL UNION, IT MUST BE PRESERVED

That was a take on Jackson's famous utterance, made at an 1830 Thomas Jefferson birthday dinner, about federal law superseding authority of individual states. (Read more about the Nullification Crisis and its Civil War ramifications here.)

|

| A circa-1844 daguerreotype of 78-year-old former president Andrew Jackson. |

During the occupancy of Memphis by Gen. [Sterling] Price’s rebel army, a Col. Brunt rendered himself forever notorious and forever infamous by defacing and partly erasing the word federal in the above inscription. The monument still stands, however, a lasting rebuke to the rebels and a reminder of the reckless and venom minded policy of some of the men who have led its armies. The word federal has not been entirely effaced. It is yet readable, and is fast coming out of the dust of anarchy and confusion which for a twelve-month [period] have obscured it.

In addition to the word "Federal," the first two letters of "Union" were chipped by "some rampant rebel," another newspaper correspondent reported, "presenting an appearance as if a small hammer had been several times struck across the obnoxious words."

Continued the correspondent: "It was a very feeble attempt at defacement of the words that grated harshly on treason's ear." The bust reportedly suffered the wrath of Rebel rabblerousers, too. (Damn kids!)

A Union soldier recalled a visit to the Court Square in late fall 1862. "...one of our company marched in, and it done me good to see them in a ring around the marble bust of General Jackson to which they showed their respects with presenting arms," wrote 30th Iowa quartermaster sergeant John Caleb Lockwood. "Upon the marble pillars upon which the bust of the general stands are cut the words, 'The Federal Union—it must be preserved.' The words 'Federal' I noticed were defaced as though it was intended to be obliterated. I thought I could see from the countenances of the citizens that we were not very welcome visitors."

|

| An uncropped version of an illustration of the Jackson monument park in Memphis from Harper's Weekly on July 5, 1862. (CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE.) |

Another Northern visitor was infuriated by the damage. "Vain attempt to obliterate the noblest utterance of Tennessee's favorite son!" he wrote. "There it stands, marred but still legible, a monument of vandalism of the perpetrators, and of the still greater vandalism and infamy of the rebels, who would not only obliterate the mute words on the marble but who have employed their mightiest energies to destroy the Federal Union itself, with all its living interests."

Now I couldn't track down "Col. Brunt," whose descendants may be aghast by his alleged behavior. As for the bust of Jackson, well, you can visit it at the D’Army Bailey County Courthouse in Memphis. Be warned: "It bears ample evidence of the turbulent reaction to Jackson."

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

- Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1862.

- Harper's Weekly, July 5, 1862.

- John Caleb Lockwood letter to his wife, Nov. 7, 1862, William Griffing's Spared & Shared site (Letter 2), accessed July 20, 2021.

- Nashville Daily Union, June 22, 1862.

- The Presbyter, Cincinnati, Ohio, July 31, 1862.

Saturday, July 17, 2021

A 'remarkable accident': How New York soldier died in Virginia

|

| An illustration, probably by Larkin Goldsmith Mead, of the grave of Corporal James Bryant and a tree upon which the soldier's name, unit and death date were etched. (Library of Congress) |

|

| Larkin Goldsmith Mead of Harper's Weekly created this illustration of a deadly lightning strike that killed 1st New York Light Artillery Corporal James Bryant in Virginia. |

|

| Corporal James Bryant's grave in Cold Harbor (Va.) National Cemetery. (Find A Grave) |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

- Harper's Weekly, July 5, 1862.

- James Bryant's pension file, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C., transcribed by Jennifer Payne (accessed July 17, 2021).

- Krick, Robert K, Civil War Weather in Virginia, University of Alabama Press, 2007.

Sunday, July 11, 2021

A visit with great granddaughter of Sam Watkins of Co. Aytch

|

| Ruth Hill McAllister at the grave of Sam Watkins, her great grandfather. |

Confession: I have not read Company Aytch, Confederate soldier Sam Watkins’ classic memoir, which puts me in a minority among my Civil War friends, acquaintances and hangers-on, according to an informal poll. I promise to rectify that, especially now that I have a copy of the latest version, signed by Watkins' great granddaughter herself.

|

| This image of Sam Watkins hangs in Ruth Hill McAllister's house. Watkins died in 1901. |

Behind us stands Zion Presbyterian Church, Watkins’ longtime place of worship built, in part, by slaves. And steps from his grave stands one of those ubiquitous (and addictive) Civil War Trails tablets. It includes this quote from Company Aytch:

"America has no north, no south, no east, no west. The sun rises over the hills and sets over the mountains, the compass just points up and down, and we can laugh now at the absurd notion of there being a north and a south. We are one and undivided."

Too bad today's America is not "one and undivided." But that’s a discussion for another day. Ruth, as sweet a lady as you’ll ever meet, invites me to her 19th-century house. There, I enjoy two slices of McAllister's freshly baked banana coffee cake with sweet tea, bond with her rambunctious but friendly dog and chat about one of the Civil War’s more fascinating characters.

|

| Visitors leave tokens of remembrance on Sam Watkins' gravestone in Columbia, Tenn. |

|

| Zion Presbyterian Church, which Sam Watkins attended, still holds services. |

Thirty-one years ago — yikes! — Ruth's family sat glued to the TV for Burns' mini-series, which may have shaded the truth a bit (see: "Gettysburg/Confederates shoes story") but opened the eyes of millions to America's greatest conflict. (Lord, I can't get enough of former newspaperman Charles McDowell's Watkins voiceover.)

|

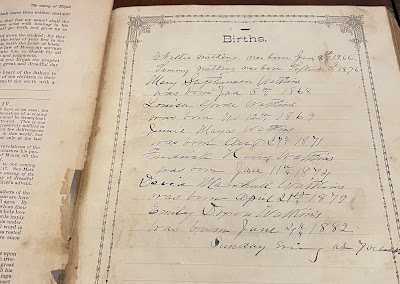

| An ancient family Bible includes a list of Watkins births. |

Watkins, who died in 1901, never dominated family discussions while McAllister was growing up. But her father had a habit of writing down notes from conversations with his mother — Watkins' daughter, Ruth's grandmother — about him on the backs of envelopes. Some of those scribblings are stuffed in the nooks and crannies of McAllister's beautiful house. (Ruth also has the ancient, Sam Watkins-signed family Bible, a neat relic to examine.)

Samuel Rush Watkins, who was promoted from private to corporal in 1864, seemed to be everywhere in the Western Theater — battles at Shiloh, Perryville, Murfreesboro/Stones River, Nashville and elsewhere. But it’s his folksy, often-eloquent writing (and razor-sharp sense of humor) that leaves me slightly in awe. A few Watkins-isms:

- "A soldier's life is not a pleasant one. It is always, at best, one of privations and hardships. The emotions of patriotism and pleasure hardly counterbalance the toil and suffering that he has to undergo in order to enjoy his patriotism and pleasure. Dying on the field of battle and glory is about the easiest duty a soldier has to undergo."

"I always shoot at privates. It was they who did the shooting and killing, and if I could kill or wound a private, why, my chances were so much the better. I always looked upon officers as harmless personages."

A close-up of Sam Watkins' gravestone -- and metal CSA

marker next to it -- in Zion Presbyterian Church Cemetery

in Columbia, Tenn.- "General [Braxton] Bragg was a disciplinarian shooter of men, and a whipper of deserters. But he was not any part of a General. As a General he was a perfect failure."

- "The lice and the camp itch were the greatest luxuries enjoyed by the private soldier. Ah, reader, they were luxuries that were appreciated. A good scratching was ecstasy. It was bliss."

- "The majority of Southern soldiers are today the most loyal to the Union. Many disown the Southern cause and have buried in forgetfulness all memory of the war."

|

| Ruth Hill McAllister gave me a copy of Company Aytch. Signed it, too. |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

Friday, July 09, 2021

Interview: Laura DeMarco, 'Lost Civil War' author. Plus, a list!

|

| The 8th Vermont monument on the Cedar Creek battlefield. |

SHENANDOAH VALLEY BATTLEFIELDS: Some of the most important battlefields of the Civil War in Virginia are buried under asphalt and concrete. A drive down Interstate Highway 81 provides a tour of Shenandoah Valley Civil War battlefield sites — planned or not. The interstate travels through the valley for 150 miles, cutting through seven battlefields as it winds through the picturesque countryside, including: Second and Third Winchester, First and Second Kernstown, Cedar Creek, Fisher’s Hill, Tom’s Brook. and the New Market battlefields.

|

| An August 1863 image of Camp Letterman. (Library of Congress) |

|

| Hard-to-get-to Fort St. Phillip in Louisiana. This is an 1898 addition to the fort. (NPS photo) |

FORT ST. PHILLIP (LA.): Founded by the Spanish in 1792, Fort St. Philip has the most fascinating history of any American fort. It was ruled by the Spanish, French, and United States, and was the location of a Civil War siege, a Civil Rights threat, and a cult. The remaining structures were severely damaged by hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005. Today, portions of the original masonry fort and rusty artillery remain abandoned and covered in overgrowth. The land is shrunk more and more by erosion each year. Fort St. Philip, which played such a vital role protecting New Orleans, is only accessible by boat or helicopter.

|

| A stereoview of Marshall House in Alexandria, Va. (Library of Congress) |

MARSHALL HOUSE (ALEXANDRIA, VA.): One of the most significant deaths in the early days of the Civil War took place not on the battlefield, but in an inn. The Marshall House at 480 King Street in Alexandria, Va., was the site of the May 24, 1861, assassination of Col. Elmer E. Ellsworth, founder of the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment and close friend of President Abraham Lincoln. It was a day that would live in infamy in the Civil War, energizing both Union and Rebel troops. The Marshall House was badly damaged in an 1873 arson, though it was rebuilt. The infamous location was demolished in 1950. But the controversy didn’t end with its removal. The Sons and Daughters of the Confederate Veterans hung a historic plaque on a new hotel on the site, The Monaco, that only mentioned Jackson, “the first martyr to the cause of Southern Independence” — not Ellsworth. The controversial sign was finally taken down in 2017 when Marriott purchased the property and renamed it The Alexandrian.

|

| Brady, post-war |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

Thursday, July 08, 2021

Strange daze: A 'hypnohistory' session at a Tennessee fort

|

| Before the hypnosis session at Fort Granger, I was a bundle of raw nerves. |

|

| Humorist/retired lawyer Jack Richards offered hypnotic suggestions while I was blindfolded. |

|

| Early morning reporting essentials at Fort Granger: toilet paper (don't ask), a notebook, and a pen. |

|

| Stay off the earthworks! |

And then come words that make me feel really queasy: “Focus on your thighs. They are the biggest part of our bodies, and we rarely think about them.”

|

| Our hypnosis session was held near the middle of Fort Granger. |

|

| An overgrown area near the war-time entrance of the fort. |

|

| Hypnotist Jack Richards walks on a trail near an imposing, earthen wall at Fort Granger. |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? Email me here.

SOURCE

- Fout, Frederick, The Darkest Days of the Civil War, 1864 and 1865, Translation of Fout’s 1902 Die Schwersten Tage des Bürgerkriegs, 1864-1865.