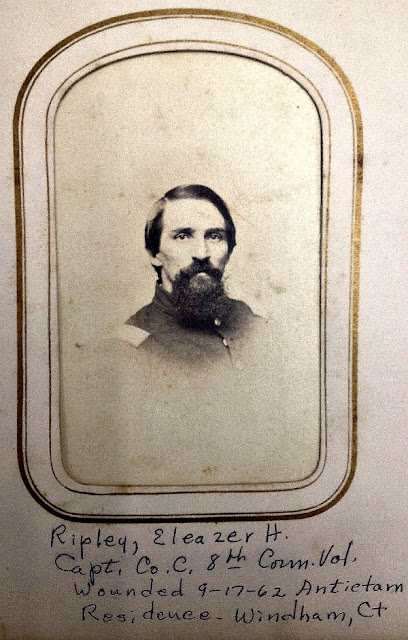

|

Corporal Lafayette Hunting of the 49th New York was mortally wounded

at Spotsylvania Courthouse on May 12, 1864. The 28-year-old soldier

died June 3, 1864.

(Photo courtesy Richard Clem) |

I first met relic hunter extraordinaire Richard Clem at Connecticut Day at Antietam on April 21, 2012. The 72-year-old retired woodworker from Hagerstown, Md., held a group of Civil War enthusiasts spellbound in front of the Antietam Visitors' Center that morning with tales of his many relic hunts with his brother, Don, in Maryland, West Virginia and Virginia during the past four decades. The brothers have unearthed 30,000 bullets (they sold 15,000 of them to a New York man), and Richard's impressive finds include three rare Civil War soldier ID discs (see photos below), including one that belonged to Corporal Lafayette Hunting of the 49th New York. Part-detective, part-amateur historian, Clem is a terrific storyteller who relishes telling the tale behind the relic. He kindly shared this story of his discovery of Hunting's ID disc and his painstaking research into the life of a soldier who died nearly 150 years ago.

By Richard E. Clem

George T. Stevens, 6th Corps surgeon with the Army of the Potomac, wrote after the war: “Under a canopy of redbud and dogwood, the 6th Corps marched into the Wilderness -- May 4th 1864.” This scene of natural and military beauty would soon be turned into one of bloody human slaughter. In fighting so fierce that a 22-inch oak tree was shot in half by small arms fire, Corporal Lafayette Hunting, 49th New York Volunteers, gave his all to preserve the Union. The Wilderness Campaign would be his last.

|

Relic hunter Richard Clem unearthed this identification

disc for Corporal Lafayette Hunting of the 49th New York in

a cornfield near Hagerstown, Md., in 1980. The reverse lists the

battles in which he fought.

(Photos courtesy Richard Clem) |

On Oct. 24 1980, while using a metal detector in an old cornfield several miles south of Hagerstown, Md., I dug up what most relic hunters only dream of finding: a Civil War identification disc. About the size of a quarter, retaining 50 percent of its original gold plate, the brass disc is inscribed:

Cpl. L. Hunting / Co. I / 49th Reg. / NY Vols. / Pembroke NY.”

The back bears the legend:

“Fought In Battles / 1861, 2 & 3 United States / Antietam / Williamsburg / 7 Days Fighting Before Richmond / Fredericksburg 1 & 2 / South Mountain / Mechanicsville / Bull Run 2nd

After discovering one of these historical gems personally inscribed to a soldier who had fought in the conflict, questions naturally surface:

Did he survive the war?

Where was he buried?

Years of research at state and national archives produced extensive material on L. Hunting, this soldier from the past. Ads placed in various Civil War publications “searching for any information on Cpl. Hunting” made it possible to contact Hunting descendants from New York to the West Coast.

Lafayette Hunting was born in 1836, in Monroe County, N.Y. In 1845, he moved with his family to Pembroke, Genesee County, just northeast of Buffalo. An 1850 census for Genesee County shows living in the Sidney and Sally Hunting household seven children, including Mary, Asa, Lafayette, Sidney Jr., Alva, Lydia and Sarah. An older daughter, Laura, had married a year earlier -- Feb. 23, 1849 -- to a Robert Swift and left home.

With the outbreak of civil war, in August 1861, 25-year-old Lafayette and his 18-year-old brother, Alva, enlisted at Forestville in the 49th New York Regiment -- both mustered in as privates in Company I. Enlistment records describe Lafayette as being of “German decent -- blue eyes -- blonde hair -- 5 foot-10 inches tall.” The younger brother was listed as “ 5 foot-10 inches tall – blue eyes – light hair.” Unfortunately, Alva’s military career was cut short suddenly by diphtheria. He died Sept. 16 1862, at Patterson Park Hospital in Baltimore. The next day -- Sept. 17 1862 -- as Lafayette was fighting Confederate forces around Dunker Church during the bloodiest day of the war at Antietam, Alva was being buried in Loudon Park Cemetery in Baltimore. Of course, the surviving Hunting had no knowledge of his brother’s death or burial.

As stamped on the ID disc, Lafayette Hunting fought in every major engagement of 1862 with the 6th Corps attached to the Army of the Potomac. On Nov. 26, 1862, he was promoted to the rank of corporal. Fought May 3 1863, the last battle to take place as listed on the tag was 2nd Fredericksburg. This indicates Corporal Hunting had purchased his keepsake in May or June 1863. There was no official ID or called in the military “dog tags” during the Civil War. This type of war medal was sold and inscribed by enterprising sutlers who followed the armies competing for the soldier’s $13-a-month pay. More of a patriotic nature, they were normally bought for 25 cents a pair -- one being sent home to wife or sweetheart, the second carried by the soldier.

|

Clem unearthed Hunting's ID disc near the hay bale in this field near Hagerstown, Md., in 1980.

(Photo courtesy Richard Clem) |

Regarding the Gettysburg Campaign -- July 1863 -- the 49th regimental history records: “The 6th Corps marched nearly all night, July 1st, and most of the day of July 2nd. They arrived on the battlefield at about 5 P.M. of the 2nd day, having marched from 35 to 37 miles over hot, dusty roads, and were well nigh exhausted.” Corporal Hunting saw little action at Gettysburg, the 49th NY being held in reserve, yet it was after the decisive Union victory he lost his ID disc in Washington County, Md.. It was here the Army of the Potomac paralleled the retreating Army of Northern Virginia nervously, anxiously waiting for the flooded Potomac River to recede for a safe crossing to Southern territory. The open field where the ID tag was found remains as it was in 1863, but like other Civil War sites, the threat of destruction from development exists on the horizon.

To escape the boring routine of winter camp life, soldiers took advantage of the time to keep in touch with folks back home. In a letter from Brandy Station, Va., dated Nov. 21, 1863, the New York soldier wrote to his family:

“Dear Parents

It has been a long time since you wrote to me – as if you have forgotten me entirely. A few days ago I got a letter from Laura. That picture is yours mother is it not. I am much pleased with it. I shall try to keep it as long as I can. Today is Saturday it has been raining all day.”

The Hunting note revealed respect for “Uncle John” Sedwick:

“Our Corps (6th Corps) was reviewed yesterday by General Sedwick our own corps general. He is a good and brave man – true to his country and cause. He goes in with energy and faith that he can whipp the cursed Rebels and he can to.”

Like so many Northern soldiers, Lafayette had nothing good to say about Washington politicians, but high praise for President Lincoln:

“If old (Henry) Halleck was out here I could shoot him with a good will. He is a traitor to the heart. So is over half of those representatives and congressmen. But we trust and believe Old Abe is alright. He is sound but has so many working against him. Father if you send those boots please direct in this way to the 6th Corps, company I, 49th Regt. NY Vols, Washington, D. C. This is all so goodby from your son. . . Lafayette Hunting.”

The correspondence ends with an "afterthought" of bitterness directed toward an 18-year-old sister, giving evidence of loneliness found in a homesick heart:

“Sarah -- I was glad to know you are well. You spoke of exchanging an old friend for a new one. I think that is what you have done. You do not seem to write to me as if you cared anything about me. If you do not take a little more pain and write oftener you will look a good while before you hear from me again. I can not do all the writing. My health is good. You must write soon – Your Brother Lafayette.”

I received from Michigan a copy of this original hand-written letter from a great-great-grandson of Laura Hunting Swift – Lafayette’s oldest sister. On Dec, 16 1863, a little over a month after mailing this letter, Lafayette re-enlisted as a veteran in the 49th NY Infantry at Brandy Station, Virginia.

In spring 1864, President Lincoln called for Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to take control of all Union armies. Hopefully, the new commander with a major campaign advancing south would force Richmond to its knees and bring an end to the war. Grant’s one big problem: Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia would make a stubborn stand in his path to the Confederate’s capital, contesting every inch of ground at places called the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor.

With a battle cry “On to Richmond,” the Army of the Potomac pushed deeper into the core of the Old Dominion. At a hamlet called Spotsylvania Court House, Lee constructed strong log and earth breastworks to slow down Grant’s determined thrust. On May 12, on what some referred to as the “killing ground,” the 49th NY lost 52 members killed or mortally wounded, its greatest number of casualties for a single battle during the entire war. A Federal soldier who witnessed the brutal engagement remembered: “Skulls were crushed with clubbed muskets and men stabbed to death with swords and bayonets thrust between the logs in the parapet which separated the combatants.”

Although a steady rain began, the deadly ordeal continued under what some historians consider “a volume of fire unprecedented in the history of warfare.” That night as both sides tried to catch their breath from fighting, several oak trees more than a foot in diameter, fell into the breastworks being shot off by musket fire. In 1902, survivors of the 49th New York Infantry placed and dedicated a monument on this sacred soil that has become known as the “Bloody Angle.” One side of the granite structure contains a list honoring those departed comrades who perished there, including the name . . . Corporal Lafayette Hunting.

According to military records, after two weeks the critically wounded Corporal Hunting was transferred from the muddy field to a hospital in Alexandria, Va. In all probability, the 28-year-old corporal never regained consciousness. Hospital records describe the fatal wound as “hit in right shoulder by minie ball -- lodge next to spine.”

An army surgeon unsuccessfully attempted to remove the bullet and noted: “When admitted patient was suffering from pneumonia. An incision was made along the track of the wound -- many pieces of bone and dead tissue removed -- patient died June 3, 1864.”

When news of Lafayette’s death reached New York, his brother, Asa, boarded a train for Virginia to bring the body home. Once reaching Alexandria, the older brother signed for the remains and on rails of steel began the sad journey north. Returning to Pembroke, the body was buried in the Brick House Cemetery next to a 21-year-old sister, Lydia, who had passed away in 1853. Before the war ended, the Hunting family moved to Evanston, Ill.. Normally this is where the Hunting saga would end; every piece of available material on the soldier from the Empire State had been compiled. However, one question kept surfacing: Was it possible that a picture or an image of Cpl. Hunting existed? If so, where? Federal documents disclose the effects found in the New York soldier’s knapsack at the time of death: “one silver watch -- $95.80 Government money -- one pocket knife -- memorandum book containing letters and photographs."

Undoubtedly, one of those photos was of his mother as mentioned in the letter, and one was of Corporal. Hunting himself. It was my guess any soldier proud enough of his military service to have purchased an ID tag, would have had pictures taken of himself.

Also found on the body was a "small silver chain." I’ll always wonder if this was the very same chain that once held the ID tag, considering the small hole found on its edge. Some things are known only to God.

At first, searching for Lafayette’s photo seemed like “searching for a needle in a haystack.” At least the needle does exist somewhere in the haystack, but in this case an image of Hunting may never have xisted. On April 17, 1985, five years after digging up the ID tag, I received a phone call from Glaphry Duff of Fallbroke, Calif.. With an excited voice, she explained: “Lafayette Hunting was my great-great-great uncle and we have a Civil War photograph of him!” The needle had just found me.

|

This miniature bible belonged to Private Alva Hunting of the

49th New York, Lafayette Hunting's younger brother. A Hunting

descendant gave this as a gift to Clem. who treasures it. Alva died

of disease on Sept. 16. 1862, one day before Lafayette fought

in the Battle of Antietam.

(Photo courtesy Richard Clem) |

Doing Hunting family research, Mrs. Duff had been in contact with Lois Brockway, historian of Corfu/Pembroke, N.Y., who gave her my phone number. Contact had been made with Lois Brockway by the author after an ad was placed in a Buffalo newspaper searching for: “. . . any information on Corp. Lafayette Hunting – 49th New York Vols.” Lois had found Lafayette’s grave and shared with me extensive material on the Hunting family. Mrs. Duff then said her cousin, Ione Goode, living in Eugene, Ore., had possession of the Hunting photo. When I called Mrs. Goode that evening, she mentioned having two sons in the U.S, Marine Corps, but neither had an interest in the Civil War and she wanted to give me Lafayette’s picture.

Several weeks later, I received by registered mail from Eugene, Ore., the “original” tintype photo of Lafayette. The same package contained another gift Mrs. Goode wanted me to have -- one I’ll cherish forever. Almost lost down in the corner of the heavy, brown envelope was a small New Testament slightly larger that a postage stamp. A note in the package explained that when Alva Hunting died in Baltimore, he was carrying this very same Bible. Somehow, the tiny book had been returned to New York and stayed in the family more than 123 years. The little heirloom made its way from Baltimore to Pembroke, N.Y., to Evanston, Ill., to Eugene, Ore., and finally back to Maryland. Inside the back cover a member of the family had written: “Alva H. Hunting -- Cherry Valley, New York -- Died in Baltimore.” An 1860 census indicates Alva was living and working on a farm in Cherry Valley, N.Y., at the time of enlistment.

During the quest to bring the 19th-century warrior to life, I journeyed to New York. On a beautiful June morning while kneeling over Lafayette’s grave in the Brick House Cemetery, I experienced a strange feeling of personal loss and grief. It was hard to accept reality that the man I had come to know was gone. Just below the surface was a soldier who had fought, suffered and died in the War Between the States for a cause he considered worthy of the supreme sacrifice. Perhaps now, the Ruler of All Battles will grant peace unto his soul until the day when all swords are broken, all artillery dismantled and they shall speak of war no more.

|

Richard Clem's prized Civil War relic hunting finds: 1) Staff officer's button;

2) 1852 gold 2 1/2 dollar coin; 3) Silver ID badge of Consider Willett in the 44th New York;

4) ID tag of John Thompson of 3rd Vermont; 5) ID tag of Lafayette Hunting of 49th New York;

6) Officer's button; and 7) ID tag of William Secor of 2nd Vermont. |