|

| Mounted on a board, this Confederate bullet wounded Union cavalryman John Boyce in the leg. |

(Click at upper right for full-screen experience.)

The last Espy Post member died in 1937, the room eventually was shuttered and the collection inside it forgotten and neglected. Some of the post's Civil War artifacts apparently were stolen. Thanks to a fund-raising effort spearheaded by the Andrew Carnegie Free Library in the 2000s, the memorial hall and artifacts were restored, and the room was officially re-opened in 2010. Today, it's billed as the best preserved and most intact G.A.R. post in the United States. Some call it a time capsule.

|

| Daniel Rice of the 102nd Pennsylvania claimed he plunged this bayonet into a Confederate at Flint Hill, Va. |

On a wall near four large windows, a huge image of the post's namesake, resplendent in his militia uniform, overlooks his domain. Wounded and captured at Gaines' Mills on June 27, 1862, Espy died behind Confederate lines on July 6, 1862; the body of the 62nd Pennsylvania officer was never found. A large image of President Lincoln, G.A.R hero, commands a prominent spot on the wall above and to the right of Espy,

But it's the war-time relics, many of which crowd the shelves of cases, that are stars of Post No. 153. And that's just as the veterans intended.

"When every veteran of the Espy Post has answered his last roll call," they decreed early in the 20th century, "we leave for our children and their children, this room full of relics hoping they may be as proud of them as we are, and that they may see that they are protected and cared for – for all time.”

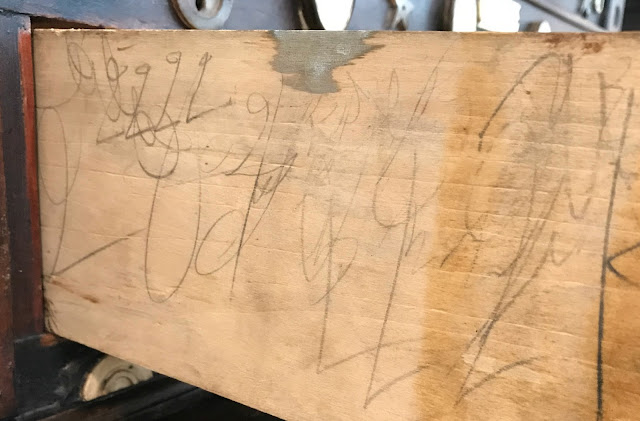

In 1911, a pamphlet of artifacts owned by the post was written by William H. H. Lea, who had served in 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery. Entries, such as these for a bayonet and a bullet, are quite detailed:

"Carried by Daniel H. Rice, Company I, bayonet 102d Regiment, Pa. Vol. Infantry, from July 11, 1862, to June 28, 1865. Was brought home by him and was in his possession over 44 years. Mr. Rice says that at the battle of Flint Hill, Va., in a charge, it came to a hand to hand conflict. He killed a rebel by plunging this bayonet into his body. Secured from Mr. Rice January, 1906, for Memorial Hall."

"This is a Confederate bullet that wounded Corporal John M. Boyce, Co. K, 1st Pa. Cavalry, at the battle of New Hope Church, Va., November 27, 1863. When taken to the hospital and his boot removed, the ball fell on the floor, his pants being inside his boot. The ball, after passing through his leg, had not force left to go through the pants and fell into the boot. Has been in his possession over 47 years. Presented by him to G.A.R. Memorial Hall, March 3, 1911."

On Saturday afternoon, Espy Post curator Diane Klinefetter and docent Martin Neaman gave me a guided tour of the fabulous collection at the Carnegie Library, about six miles southwest of Pittsburgh. I photographed artifacts from the post collection, each numbered to correspond with a description in Lea's 1911 pamphlet. (Click on images to enlarge.)

(Espy Post hours: Ongoing tours on Saturdays between 11 a.m. and 3 p.m.. Admission is free. Call 412-276-3456 for weekday appointments.)

"CANTEEN: Was picked up by Wm. P. Mansfield, then a boy eight years old, canteen on the battlefield of Chancellorsville, Va., some time after the battle while in company with his father and grandfather, their home being only 10 miles from the battlefield. The canteen was painted some years ago by his sister, to keep it from rusting. Was procured from Wm. P. Mansfield of Washington, D.C., January, 1906, in his possession over 40 years."

"SHELLS: Three pieces of shell were found by Matthew Quay Corbett on the battlefield of Gettysburg in August, 1906, in the field over which General Pickett charged, July 3, 1863. Secured from him for Memorial Hall, March 16, 1909. Shell fragments; 1 triangular with part of band on it; one circular piece; one with fuse threads inside."

"HAND GRENADE: Secured at hand grenade government sale of army supplies in Pittsburgh, Pa., January, 1906, by W. H. H. Lea. The shell was patented August 20, 1861. Was used to defend forts and breast work by throwing them by hand among the charging columns when near the fort or breast works. Placed in Memorial Hall January, 1906."

"COTTON: Was picked from the cotton bushes in 1881 by W. H. H. Lea, late Lieutenant of Co. I, 112th Reg., Pa. Vols., while on a visit to the Virginia battlefield, from the narrow strip of ground between the Union and rebel lines and directly in front of the rebel fort at Petersburg, Va., blown up July 30, 1864. Over this ground the charging columns passed. Almost every foot of this ground was covered with Union dead or stained by as brave blood as ever flowed from the veins of American soldiers. Has been in possession of W. H. H. Lea for 25 years. Secured from him January, 1906, for Memorial Hall."

"SIX BULLETS: Were secured by W. H. H. Lea, Co. I, 112th Regt., Pa. Vet. Vols., while visiting the battlefield of Fredericksburg, Va., October 23, 1909. Had laid on the field for over 40 years. The bullets were collected from different parts of the field. Placed in Memorial Hall January, 1911. One .69 caliber; four .58 caliber;

one .54 caliber."

"PINE WOOD AND BULLET: Wood was cut from the battlefield of Cold Harbor, Va., in 1889. Bullet was found while working into flooring boards at the planing mill of Thomas Stagg, Cary Street, below 14th Street, Richmond, Va., in 1890. Was worked by a Confederate soldier, and by him turned over to D. E. McLean of Wilcox Street, Carnegie, who was working in the mill at the time. Has been in D. E. McLean’s possession 16 years. Secured from him for Memorial Hall, May 10, 1906. Tongue-in-groove molding, approximately 2″ x 4″."

"MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTION OF U.S & AND C.S. RELICS: From the battlefield of the Wilderness, Spottsylvania and Travillians, Va. Found by Wm. P. Mansfield, a resident of Spottsylvania Co., Va., now of Washington, D.C. Secured from him January, 1906, and were in his possession over 40 years."

"PINE KNOT WITH GRAPE SHOT: Pine knot with grape shot embedded was found on the battlefield of Chickamauga, Tenn., in 1900, by A. B. Pitkens of Providence, R.I. Was by him presented to James J. Brown on March 26, 1900. Several years later, when Mr. Brown [was] removing south, he presented it to Dr. R. L. Walker, Sr. Secured from Dr. Walker for Memorial Hall, May, 1906."