|

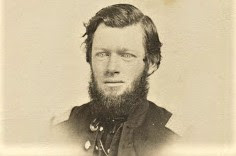

| 46th Pennsylvania Captain George A. Brooks. (Brooks images: Ben Myers collection.) |

After just three hours' sleep, Captain George A. Brooks awoke to darkness on the morning of Sept. 17, 1862, still wearing his equipment. The 28-year-old officer ached from wounds suffered a month earlier at Cedar Mountain, and his uniform was damp from a combination of sweat and rain the previous day.

But Brooks didn’t have time to dwell on those concerns.

|

| Joseph F. Knipe commanded the 46th Pennsylvania during the early years of the war. (Library of Congress) |

But when Robert E. Lee invaded Maryland, both men returned to their unit knowing the Pennsylvanians would need officers to lead them.

With instructions to prepare to advance, Brooks -- the only captain with the 46th at Antietam -- moved off into the pre-dawn hours to rouse what few men he had left. The regiment numbered little more than a full company, but it was a veteran group, and the soldiers quickly fell in with little instruction. Coffee would have to wait.

Brooks paused to watch the men and thought back to just a year earlier, when most of them had been mere boys, full of patriotism. He was proud to have helped mold them into soldiers. He prayed they would prevail and for the restoration of the Union.

For the next hour, the XII Corps, the 46th Pennsylvania among them, crept forward at a frustratingly slow rate. They stopped and started, deployed, and countermarched, sometimes pausing just long enough for the men to think they could get some coffee after all. But as soon as small fires were kindled, the order would come to continue.

No one in the ranks knew exactly what was happening, but the occasional popping of skirmishers the night before had turned into rifle volleys and cannon shots. A battle was still a ways off, but they knew they were slowly marching toward a big one.

|

| A modern view looking north on the Smoketown Road; the 46th Pennsylvania advanced on this road (toward camera) on the morning of Sept. 17, 1862. (Ben Myers) |

When they made their longest halt, artillery shells flew overhead and wounded from General Joseph Hooker’s Corps streamed past, making their way to the rear. Over half of Brooks’ brigade were new Pennsylvania troops, the 124th, 125th, and 128th regiments, who had spent just a month in the service. The green soldiers watched wide-eyed, one of them remembering that as the shells screamed by “most men ducked and then would straighten up with a sickly kind of grin.”

|

| The 46th Pennsylvania deployed with its brigade into the East Woods. American Citizen: The Civil War Writings of Captain George A. Brooks (Sunbury Press, 2019). |

The plan was fairly simple: The 46th Pennsylvania, along with the rest of their brigade, would deploy to the left of Hooker’s men in David R. Miller cornfield with the aim of outflanking the Confederates. When the order came, the 10th Maine moved off to the left, and the new 125th Pennsylvania moved right, toward Miller's Cornfield, to form the anchor with Hooker’s line. The 700-man-strong 128th Pennsylvania, along with the much smaller 46th Pennsylvania and 28th New York, would form a line in between the 10th and 125th.

But the plan fell apart within minutes.

Brooks and his fellow line officers ordered the men forward, but it was tough going. The regiments weren’t properly spaced to deploy into line -- an oversight by the new corps commander, Major General Joseph K. F. Mansfield, who was worried the new Pennsylvania troops would break and run. Brooks’ 46th and the 28th New York managed to line up as they started into the East Woods, barely flinching as bullets and artillery rained in. They started to fire back, leveling one steady volley after another.

|

| This image of Knap’s Pennsylvania Battery by Alexander Gardner, taken two days after the battle, shows the famous East Woods in the background. (Library of Congress) |

The 128th Pennsylvania, however, didn’t come up onto line. It panicked as it tried to deploy, and within moments its colonel was killed and lieutenant colonel wounded. Officers from the 46th Pennsylvania and 28th New York rushed to assist the stricken regiment, hoping to line it up and relieve the pressure against the dwindling veteran regiments. But they did so amidst Confederate snipers in the trees raining bullets into them.

|

| George A. Brooks, killed at Antietam, was buried at Harrisburg (Pa.) Cemetery. |

The summer prior, Captain Brooks had written home to his local newspaper. The war was going poorly as the regiment languished, inactive, in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia. On top of that, Brooks was mired in a long familial dispute. Despite those issues, he was homesick and bored, longing to see his wife and young son. But he pushed his concerns aside to encourage others to join the war effort -- a cause for which he was devoted:

"Move with us 'on to Richmond,' and aid our noble leader in reducing the stronghold of rebellion, till, like the ancient temple of Jerusalem, 'not one stone shall be left standing upon another.'

"True, it will cost immense amounts of treasure and blood; many noble lives will be sacrificed, but the great principles of liberty must be perpetuated; our government, in all its original purity, must be preserved. Let Pennsylvanians then rally around the old standard... and before the festive days of Christmas make the annual round you will have returned to your homes with the consciousness of having performed a sacred duty, and earned the glorious title of an 'American citizen.' ”

Learn more about Captain Brooks in American Citizen: The Civil War Writings of Captain George A. Brooks, 46th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (Sunbury Press, 2019).

No comments:

Post a Comment