|

| Pinfire cartridges manufactured by C.D. Leet & Co. of Springfield, Mass. (Aaron Newcomer via Wikimedia Commons) |

As soon as he heard the explosion, Charles M. Atwood knew his greatest fear had been realized.

“There goes Leet's cartridge factory,” the young man said to himself. Then he sprinted from his boardinghouse toward his former place of employment blocks away, in the heart of Springfield, Massachusetts.

'Human gore': More on deadly Civil War explosions on my blog

BOOM! BOOM! BOOM!

At 2:30 p.m. on March 16, 1864, a series of massive explosions ripped through the C.D. Leet & Co. cartridge factory on Market Street, reverberating across town — not far from the national armory that supplied the U.S. Army with thousands of Springfield muskets and other weaponry. Leet's employed 23 women and girls and 24 men for the production of metallic cartridges for Joslyn and Spencer carbines and other weapons.

|

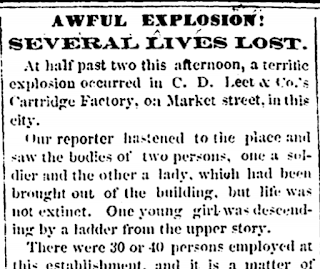

| Headline in the Springfield Union on March 16, 1864. |

But that accident paled in comparison with this tragedy, which underscored dangers faced by ammunition workers on the home front. The final death toll reached nine — four in the explosions and subsequent fire, five afterward. Nearly a dozen suffered injuries.

The next day, officials convened a coroner's inquest to determine what caused the catastrophe — the second such disaster at a Civil War munition factory in a little more than a year. On March 13, 1863, more than 40 female workers died in an explosion at a Confederate arsenal on Brown’s Island in Richmond. More than 130 workers, mostly female, died in explosions the year before at the Allegheny Arsenal near Pittsburgh, an arsenal in Jackson, Miss., and a fireworks-turned-cartridge factory in Philadelphia.

|

| A label for metallic Spencer carbine cartridges made at the C.D. Leet factory in Springfield, Mass. (Wood Museum of Springfield History) |

The Springfield tragedy revealed the best — and worst — of humanity.

Atwood and 10th Massachusetts Lieutenant Lemuel Oscar Eaton and Private John Nye — soldiers who just happened to be in the neighborhood — dashed into the burning factory to aid victims. Atwood knew where workers stored gunpowder, and to avoid an even greater disaster, he rushed to help remove it. As Eaton tossed powder cases out of harm's way, another explosion rocked the building, briefly knocking the 32-year-old officer senseless. He was due to return to his regiment the next day.

After removing four cases, Atwood and Eaton proceeded to move another when it exploded, burning Atwood on the face and hands. Miraculously, both escaped without serious injuries. (Two months later, Eaton suffered a serious leg wound at the Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse.) Nye suffered burns but also recovered to return to his regiment.

Upon their arrival shortly after the first blast, Springfield firemen discovered a grim scene: flames leaping from shattered windows, huge columns of smoke, wailing victims, scores of gawkers and friends and family searching for loved ones employed at the factory.

Fourteen screaming girls leaped from the third floor of the factory onto the roof of the shop next door. They "were removed by ladders," the Springfield Republican reported, after firemen and others made "the most frantic threats” to keep them from jumping to the ground.

"The conduct of the firemen and all those who volunteered to enter the burning building was heroic in no light sense of the word," the newspaper wrote. "Among the most active and efficient of all the attendants were eight or ten of our city physicians, who were unceasing in their efforts to relieve the sufferings of the unfortunate men and women."

Rescuers wrapped a burning victim in a blanket and took her to a nearby house after she leaped or was blown out of an upper-story window. In one of the most heartrending sights, a severely burned female victim, crying and groaning in agony, begged for arsenic or any other deadly concoction to end her misery.

GOOGLE STREET VIEW: Approximate location of long-gone C.D. Leet & Co. factory.

"The appearance of those who were worst injured was shocking beyond description," the Republican reported. "Every garment of their clothing was blown or burnt off, and some of them were literally a blistered and blackened mass from head to foot. So badly were they burnt that it is surprising that they were not instantly killed."

Calista Evans, a widow from New York, suffered burns over her entire body and died the next day at her sister’s house in Springfield. It was only her second day on the job. Laura Bishop, who only recently had returned to work after an accident at the factory, also died. The 22-year-old's injuries, the newspaper wrote, were of the same “shocking character” as the other horribly burned women.

The tragedy crushed one family. John Herbert Simpson, a 27th Massachusetts veteran, stood near the loading room when the first explosion rocked the building. “Shockingly burnt,” the 19-year-old died the next morning. His 15-year-old sister, Anna, also suffered severe injuries.

Atwood and 10th Massachusetts Lieutenant Lemuel Oscar Eaton and Private John Nye — soldiers who just happened to be in the neighborhood — dashed into the burning factory to aid victims. Atwood knew where workers stored gunpowder, and to avoid an even greater disaster, he rushed to help remove it. As Eaton tossed powder cases out of harm's way, another explosion rocked the building, briefly knocking the 32-year-old officer senseless. He was due to return to his regiment the next day.

|

| Lieutenant Lemuel Oscar Eaton of the 10th Massachusetts dashed into the burning factory. (The 10th Regiment Massachusetts VolunteerInfantry, 1861-1864) |

Upon their arrival shortly after the first blast, Springfield firemen discovered a grim scene: flames leaping from shattered windows, huge columns of smoke, wailing victims, scores of gawkers and friends and family searching for loved ones employed at the factory.

Fourteen screaming girls leaped from the third floor of the factory onto the roof of the shop next door. They "were removed by ladders," the Springfield Republican reported, after firemen and others made "the most frantic threats” to keep them from jumping to the ground.

"The conduct of the firemen and all those who volunteered to enter the burning building was heroic in no light sense of the word," the newspaper wrote. "Among the most active and efficient of all the attendants were eight or ten of our city physicians, who were unceasing in their efforts to relieve the sufferings of the unfortunate men and women."

Rescuers wrapped a burning victim in a blanket and took her to a nearby house after she leaped or was blown out of an upper-story window. In one of the most heartrending sights, a severely burned female victim, crying and groaning in agony, begged for arsenic or any other deadly concoction to end her misery.

GOOGLE STREET VIEW: Approximate location of long-gone C.D. Leet & Co. factory.

"The appearance of those who were worst injured was shocking beyond description," the Republican reported. "Every garment of their clothing was blown or burnt off, and some of them were literally a blistered and blackened mass from head to foot. So badly were they burnt that it is surprising that they were not instantly killed."

Calista Evans, a widow from New York, suffered burns over her entire body and died the next day at her sister’s house in Springfield. It was only her second day on the job. Laura Bishop, who only recently had returned to work after an accident at the factory, also died. The 22-year-old's injuries, the newspaper wrote, were of the same “shocking character” as the other horribly burned women.

|

| Gravesite at Saxton's River Cemetery in Vermont for Laura Bishop, who was killed in the Springfield cartridge factory disaster. (Find A Grave) |

“The suddenness of the affliction has prostrated Mrs. Simpson,” the Republican wrote about the siblings’ mother, “and the best of medical care can only restore her to health.”

Leet business partners Willard Hall and Horace Richardson also died the day after the explosions. Hall, who supervised 20 men and women, suffered severe burns on his head and chest; Richardson, who managed the gunpowder and supervised three young women, fell through a set of stairs and into the cellar after the final explosion. He was attempting to save girls on the second floor.

Jane E. Goss also suffered severe burns in the explosion — her first day at work at the factory — and died nearly three weeks later. At the depot, Joshua Bellows — who later enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts Heavy Artillery — identified the remains of his adopted daughter, 17-year-old Frances.

Leet business partners Willard Hall and Horace Richardson also died the day after the explosions. Hall, who supervised 20 men and women, suffered severe burns on his head and chest; Richardson, who managed the gunpowder and supervised three young women, fell through a set of stairs and into the cellar after the final explosion. He was attempting to save girls on the second floor.

Jane E. Goss also suffered severe burns in the explosion — her first day at work at the factory — and died nearly three weeks later. At the depot, Joshua Bellows — who later enlisted in the 4th Massachusetts Heavy Artillery — identified the remains of his adopted daughter, 17-year-old Frances.

The injured, meanwhile, suffered terribly.

“Nearly all of those who were burned have complained of being cold,” the local newspaper wrote, “and have fainted upon breathing cold air.” The disaster drove a young female factory worker from West Springfield "insane," according to a report.

Do you know more about the Springfield tragedy? Email me at jbankstx@comcast.net

Underscoring the horror, depraved onlookers picked up ghastly souvenirs: pieces of burnt flesh and fingers of victims. The following day, a crowd gathered to examine the disaster area. Some of the ghouls among them snatched “any piece of a partially burned dress, or other scrap." the Republican reported, “as a memento of the terrible scene.”

Unsurprisingly, intense heat and fire caused the discharge of bullets from completed cartridges. Two went through the hat of contractor Jesse Button, who aided victims inside the factory and escaped with only minor injuries. Another narrowly missed the head of a woman who was sewing at her workplace on Main Street. Yet another zipped into a nearby dental office but caused no injuries.

At the coroner's jury of inquest, a six-person panel vigorously questioned Leet employees about safety procedures, potential causes of the explosions and more.

|

| A close-up of the weather-worn memorial in Springfield (Mass.) Cemetery for John Herbert Simpson, a victim of the disaster at the C.D. Leet & Co. cartridge factory. (Find A Grave) |

Cartridge production started on the third floor — employees kept the highly combustible fulminating powder there wet in a paste form to prevent accidental explosions. After the fulminate dried, workers married it to the cartridges, which female employees charged with powder from flasks in the second-floor loading room. The cartridges were eventually prepared there for shipment in cardboard boxes.

Minnie Russell worked in the loading room, where workers inserted bullets into cartridges. She testified that on the morning of the explosions, Leet urged female employees to sweep up excess gunpowder, even “if it took half their time.” Charles Smith called his employers “very careful men, none more so. [I] have heard them talk very hard to the hands.”

But Leet himself testified about a questionable practice at his factory: Although he did not allow cigar smoking, he was OK with friends lighting up as they left, passing cases of gunpowder in the process. Paradoxically, Leet — who had been involved in cartridge manufacturing since 1857-— emphasized the strict safety measures in place to prevent explosions.

Ultimately, the investigation determined the chain-reaction catastrophe began in the second-floor loading room. A cartridge apparently exploded, its sheet of flame touching off another blast fueled by fulminate and gunpowder. Then a massive blast momentarily lifted the third floor. In the chaos, some panic-stricken employees descended the stairs, their burning clothes igniting cases of gunpowder. Lucy S. Howland, who worked in the loading room, testified she was sent tumbling into the cellar — “all afire and burned awfully" — when the stairs collapsed. She somehow crawled from the burning building.

Officials reprimanded Leet, who was not in the factory when distaster struck, for woeful safety procedures.

“Hazardous,” “highly censurable,” “highly reprehensible,” the coroner’s investigation called his operation. In a subsequent investigation by the U.S. government, an inspector called Leet’s copper cartridges and the compounds used inside them “exceedingly dangerous for magazines and transportation.”

But Leet, who wasn’t charged with a crime, re-opened his factory weeks later.

The war — and cartridge making — dragged on.

SOURCES

But Leet, who wasn’t charged with a crime, re-opened his factory weeks later.

The war — and cartridge making — dragged on.

-- Have something to add, correct? E-mail me at jbankstx@comcast.net

SOURCES

- Fall River (Mass.) Daily Evening News, April 13, 1864

- Hartford Daily Courant, March 28, 1864

- Springfield Republican, Feb. 20, March 17, 19, 22, 1864

- "The Market Street Explosion," The Gun Report magazine, Alan Hassell, 1989. (U.S. government investigator quoted by Hassell from National Archives records group 156, no. 21.)

- 1860 U.S. census

No comments:

Post a Comment