|

| A CSX train heads toward Dutchman's Curve, site of the deadliest train accident in U.S. history. |

Gingerly navigating piles of rocks, I make my way down the embankment to the railroad track. Ominous weather threatens but doesn't deter a visit near a bend in the line called Dutchman's Curve -- site of the deadliest train accident in American history.

Fifteen yards away, three teen-aged boys fish in a creek; beyond them, on a rise, a strip mall. Steps away, a kaleidoscope of graffiti covers a bridge abutment. Thick, deep-green woods and brush border the track.

|

| Grafitti-covered bridge abutment near Dutchman's Curve. |

Shortly after 7 a.m. on July 9, 1918, as World War I grinded on overseas, two packed trains traveling between 50-60 mph collided on this track. More than 100 died in the accident; most of the dead were African-American laborers en route to work at the DuPont munitions plant in Old Hickory -- "Powder City" the company town near Nashville was called.

Bound for Memphis, Train No. 4 included a locomotive, two mail and baggage cars and six wooden coaches. Headed for Nashville, Train No. 1 included a locomotive, a baggage car, six wooden coaches and two steel Pullman sleeping cars. Blacks traveled in the rickety, wooden Civil War-era cars while whites were in the Pullmans.

Thousands in Nashville gathered at the scene; as many as 50,000 reportedly visited the site. What they saw was gruesome and heart-rending: mangled bodies and body parts, blood everywhere and anguished survivors and relatives searching for loved ones in the wreckage amid the cornfields.

|

| Thousands viewed the aftermath of the grisly accident. This photo appeared in the Nashville Tennessean. |

|

| Up ahead: Dutchman's Curve. |

|

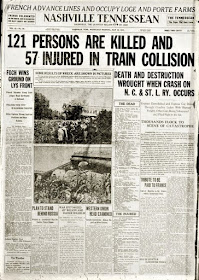

| Front page of Nashville Tennessean on July 10, 1918. |

"Thomas W. Dickerson, baggage man on No. 4," "An unidentified soldier, address unknown," "Two unidentified dead" ...

And under a separate category, a list of "Colored" dead was published:

"Oliver Hope, Craggie Hope, Tenn.," "Nine unidentified women," "Thirty unidentified men." ...

By 10 p.m., the tracks were cleared. Days later, coverage of the train accident waned, replaced by news about the Great War. An investigation concluded the crew of Train No. 4 was largely to blame for the tragedy. Decades later, David Allen Coe recorded a song about it:

"Now every July 9th a few miles west of town. To this day some folks say. You can hear that mournful sound.”

Moments before I depart, a loud whistle eerily toots in the near-distance. A distinctive clickety-clack grows louder. Another Nashville-bound train rumbles down the track and under an overpass.

Dutchman's Curve is dead ahead.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCE

-- Nashville Tennessean, July 10, 1918.

G'Day John,

ReplyDeleteExcellent blog post... as always!

Cheers,

Rob Far North Queensland, Au