|

| An interior view of the damage on the first floor at Ford's Theatre. (Library of Congress) (CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

|

| A view into Ford's Theatre shows rubble, chairs and desks in the ruins. (Library of Congress) |

In all, 23 workers inside the building, including Civil War veterans, died in the tragedy on June 9, 1893. Ramshackle Ford's Theatre, where John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Lincoln on April 14, 1865, housed hundreds of clerks who worked for the War Department’s Records and Pensions Division.

The story of the awful day — told in my lengthy feature in the August 2019 issue of Civil War Times — is one of sublime courage, narrow escapes ... and a large, white cat that loitered in the building's nooks and crannies.

Reporters described harrowing scenes at the 10th Street site near the White House. A man with a crushed arm used his other arm to drag a victim from the wreckage. Rescue workers discovered another man sticking head first in the debris but still barely breathing.

"Soon they had uncovered his legs, which moved feebly, showing he was still alive," a newspaper reported. "As fast as human hands could work those rescuers did and soon they had the unfortunate out. He was alive when he was brought into the air, but he died before he reached the ambulance in the street."

Added the newspaper: "This was but one of the many scenes attending the most horrible and inexcusable accident that ever occurred in the city of Washington."

Businesses and homes in the immediate area became makeshift hospitals. Onlookers, including anguished relatives of those who worked in the building, climbed atop rooftops to watch the rescue effort unfold.

The story of the awful day — told in my lengthy feature in the August 2019 issue of Civil War Times — is one of sublime courage, narrow escapes ... and a large, white cat that loitered in the building's nooks and crannies.

|

| Newspaper coverage of the tragedy was extensive. |

"Soon they had uncovered his legs, which moved feebly, showing he was still alive," a newspaper reported. "As fast as human hands could work those rescuers did and soon they had the unfortunate out. He was alive when he was brought into the air, but he died before he reached the ambulance in the street."

Added the newspaper: "This was but one of the many scenes attending the most horrible and inexcusable accident that ever occurred in the city of Washington."

Businesses and homes in the immediate area became makeshift hospitals. Onlookers, including anguished relatives of those who worked in the building, climbed atop rooftops to watch the rescue effort unfold.

|

| Coverage in the Washington Post included a diagram of the layout of workers' desks on the third floor at Ford's Theatre. |

They “seemed delirious,” he recalled, “and had to be held to keep them from jumping out.”

One clerk thought the building had been dynamited. Dust lingered in the air, making it difficult to breath.

In a panic, some employees jumped from the second floor, apparently bracing their fall on a Ford’s Theatre awning. At least one man saved himself by leaping upon the awning of a tobacco store next door.

In a panic, some employees jumped from the second floor, apparently bracing their fall on a Ford’s Theatre awning. At least one man saved himself by leaping upon the awning of a tobacco store next door.

Buried under debris, survivor James H. Howard prayed. “Such faith could not fail to impress the entire office,” a newspaper noted decades later, “with the earnestness of his belief in God as a ready help in a time of trouble.” Perhaps inspired by his good fortune, Howard eventually became a lay evangelist.

Shortly before the collapse, Jeremiah Daley left his desk to go to another part of the building. He was among those who fell into the chasm. He died on an operating table as surgeons dressed his wounds. The 22-year-old clerk’s desk remained where he left it, unmoved. Days earlier, Daley’s father had been fired from his job as watchman at the Department of the Interior. En route home to Pennsylvania, Mr. Daley instead rushed to the local hospital, where he identified his son’s body.

Newspapers published accounts of serendipitous escapes.

Shortly before the collapse, Jeremiah Daley left his desk to go to another part of the building. He was among those who fell into the chasm. He died on an operating table as surgeons dressed his wounds. The 22-year-old clerk’s desk remained where he left it, unmoved. Days earlier, Daley’s father had been fired from his job as watchman at the Department of the Interior. En route home to Pennsylvania, Mr. Daley instead rushed to the local hospital, where he identified his son’s body.

Newspapers published accounts of serendipitous escapes.

A clerk from Maryland tumbled from the third floor to the first floor, miraculously avoiding a deluge of iron girders and bricks. After treatment for a broken left arm and lacerated leg, he “walked about the city congratulating himself on his escape from death.”

A Texan on the second floor survived because he went to the third floor on an errand. Returning to his work space minutes later, he saw only an abyss once occupied by a floor and his desk. Another clerk demonstrated the life-saving power of alcohol. He had left work earlier that morning for a cocktail, thus missing the calamity. Afterward, he returned to grab his coat in the ruins.

The Washington Post published extensive coverage of the disaster, including an impressive diagram showing the stationing of clerks in the doomed building,

When a Post reporter visited the home of Dr. Burrows Nelson, whose body was the last one recovered, the victim's young son greeted him.

|

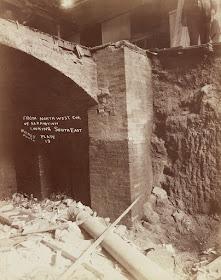

| Damage to a brick arch on the building near the White House. (Library of Congress) |

When a Post reporter visited the home of Dr. Burrows Nelson, whose body was the last one recovered, the victim's young son greeted him.

“Say, mister, when is papa coming home?” asked the tearful boy. “He will come home tomorrow, won’t he?”

A dentist, Nelson also worked as a clerk to make ends meet. His wife was pregnant with their sixth child. Nelson’s family thought he had taken the day off to go fishing.

An investigation determined the building collapsed because a pier had given way during excavation in the basement for an electric-light plant.

As for the large, white cat, a good Samaritan rescued the feline in the ruins and carried it to safety.

SOURCES USED IN CIVIL WAR TIMES FEATURE

An investigation determined the building collapsed because a pier had given way during excavation in the basement for an electric-light plant.

As for the large, white cat, a good Samaritan rescued the feline in the ruins and carried it to safety.

|

| A newspaper called the tragedy an "inexcusable accident." (Library of Congress) |

|

| An image of the debris and brick supporting arch. (Library of Congress) |

|

| Twenty-three workers at Ford's Theatre died in the collapse of the building. (Library of Congress) |

|

| Among the dead were workers who plunged from the third floor "in a chasm of death." Here's another interior view. (Library of Congress) |

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES USED IN CIVIL WAR TIMES FEATURE

- Baltimore Sun, June 10, 1893

- Bucks County Gazette, Bristol, Pa., June 15, 1893

- New York Tribune, June 10, 1893

- The Brooklyn (N.Y.) Eagle, June 9, 1893

- The National Tribune, July 13, 1893, Oct. 12, 1893

- The New York Age, Jan. 25, 1936

- The Philadelphia Inquirer, June 10, 1893

- The Washington Evening Star, March 2, 1878, June 9, 12, 1893

- The Washington Post, June 10, 1893

- Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 10, 1893.

Thanks John - I had not known this about Ford's Theatre - will be sure to read your article when it arrives.

ReplyDeleteAnother awesome tale from an excellent historian

ReplyDeleteI have heard that the Ford's theatre was moved. Is this right and did this collapse happened after the move?

ReplyDeleteFord's Theatre was never moved. It was extensively renovated and little from its 1865 interior remains.

Delete