|

Face of inscribed canteen that belonged to Confederate cavalaryman Richard Sims.

(Photo: Richard E. Clem) |

Like this blog on Facebook.

Relic hunter Richard Clem's tales have been told frequently on my blog. In this post, Clem, a lifelong resident of Washington County in Maryland, tells the story of a rare Confederate canteen with ties to Antietam and Gettysburg.

|

| Richard Clem |

By Richard E. Clem

Designed to carry water, the old wood canteen also carried a hand-carved inscription that one day would be read worldwide. With the original owner’s name and regiment cut into its face, the heirloom traveled from the coastal region of South Carolina to the farm of Daniel Wolf in western Maryland. Although once carried by a Confederate cavalryman, it remained well preserved for years in a dusty, dark attic.

The canteen was recently discovered while its owner was preparing to move to a retirement home. It seems she had lived with her mother, who stored the vintage canteen in their attic about 1936. Not knowing exactly what it was, she handed it to the author, explaining, “I think it was an old toy the kids once played with.” Another member of the family suggested, “I was thinking of using it as a flower vase.”

Apparently the owner’s mother inherited the mysterious relic from her father, and no one knew what it was. After a closer examination and noticing letters pertaining to “South Carolina,” an idea surfaced it could be connected to the Civil War. Then the owner mentioned, “It has been handed down through the family and belonged to my great-grandfather, Daniel Wolf. He preached in the Manor Church and the Dunker Church on the Antietam battlefield.”

Those words got my full attention,

With this clue, it was decided to return to the “Days of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields” to try to discover who the Rebel was who once drank from this rustic canteen.

|

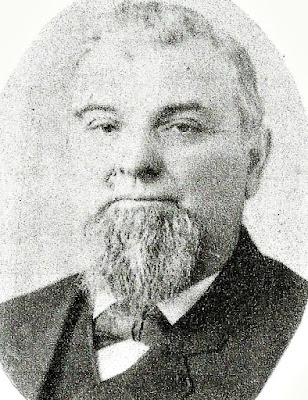

| Reverend Daniel Wolf and his wife, Ann Maria. (Courtesy Wolf family) |

Research locally revealed Daniel Wolf was born Aug. 11, 1825, at his father’s homestead in southern Washington County, Md. Daniel spent his entire life farming the old home place along Manor Church Road, just two miles east of the little town of Tilghmanton. In 1850, he married Ann Maria Rowland from Washington County. To this union came a blessing of eight daughters and three sons. One of Wolf’s daughters was the grandmother of the owner of the wood canteen.

Possessing great knowledge of the Scriptures, Daniel Wolf became a beloved and respected minister of the German Baptist Brethren Church, known today as the Church of the Brethren. Reverend Wolf’s strong stand on slavery and the evils of war served as fodder for many sermons delivered in the nearby Manor Church and in the famous Dunker Church, just south of his home on the Antietam battlefield. The Dunker Church was a branch of the Manor Church built simply to establish a church near Sharpsburg.

On Aug. 16, 1899, the earthly journey of the 74-year-old preacher ended. The body was buried in Manor Church Cemetery within view of his farm. At an unknown time, this farmer-preacher had acquired the rare Confederate canteen. What makes the 154-year-old artifact remarkable besides being made of wood is the hand-carved legend on its face:

“R. Sims, Co. I, 1st R. So. Ca., V (c) C.”

|

PRESENT DAY: Greatly in need of exterior repair, the former home of Daniel Wolf.

(Photo Richard E. Clem) |

With reverence I held this piece of Southern history. The letter “R” represents the first letter of the cavalryman’s first name, His last name is “Sims.” Beneath the name is cut “Co. I,” standing for “Company I.” Perpendicular to the right of the name and company is etched “1st R. So. Ca. V (c) C.” It took a few seconds to figure these letters stood for “1st Regiment, South Carolina, Volunteer Cavalry.” With closer study, a letter “C” can be found beneath the letter “V.” In the author’s opinion, this Confederate trooper intended to cut “Cav.,” an abbreviation for “Cavalry.” Nearing the edge of the canteen, however, and running out of space, the letters “V. C.” (Volunteer Cavalry) were substituted. A large “R” was cut on one side of the rare relic. It is believed Sims originally started to carve his name, etc. on this side, but for an unknown reason finished the inscription on the reverse side.

When the Civil War began, the South was far from being prepared in the way of raw material. By the end of the conflict, the Confederate States were melting bronze church bells and anything else they could get their hands on to produce implements of war. To preserve metal, especially iron and tin, some Southern canteens were manufactured from wood.

Known as the “cedar drum” style, these hardwood vessels (7 ½ inches in diameter x 2 ½ inches in width or depth) were also made of maple and cherry. Each consisted of two, round face plates. Around the circumference were 10 to 12 small slates grooved to receive the face plates -- all held together with two thin metal bands. A wooden maple spout to drink through was then “popped” into the top. Each canteen held about one quart of water or other liquid refreshment a Rebel chose to consume. Once the canteen was filled with liquid, the wood swelled, making it water-tight. A cork or wood stopper was then pressed into the spout, and leather straps were attached so it could be carried over the shoulder or, in the case of cavalry, hung from a saddle horn.

In some respects, the wood canteen had an advantage over their metal counterparts. Some Confederate soldiers noted water stayed cooler and tasted sweeter in these wood containers. The wood canteen had another practical purpose. With a sharp pocket knife, the owner’s name, regiment, etc. could be carved into the surface, making identification of a soldier easier in case of death. (Soldier ID tags were extremely rare during the Civil War.)

|

Natural spring beside Reverend Wolf’s home where Sims’ canteen

may have possibly been found. Daniel and Ann Maria Wolf

are buried in the Manor Church Cemetery in the background.

(Photo: Richard E. Clem) |

Who was “R Sims,” the Rebel cavalryman? How did his personal identified canteen get from South Carolina into the hands of Reverend Daniel Wolf in Maryland? Again, research started locally.

The native limestone, two-story home once owned by Reverend Wolf still stands on 188 acres just north of Antietam battlefield. With the location of Wolf’s farmstead being near the battlefield, it was naturally assumed the old canteen came out of the bloody struggle of Antietam. Wrong! The boys in the 1st South Carolina Cavalry were guarding defenses around Charleston when the battle was fought on Sept. 17, 1862. However, Confederate soldiers were in the area of Wolf’s homestead in July 1863, following the battle at Gettysburg. So the next step was to determine if “R. Sims” was at Gettysburg. According to Federal archives, Private Richard Sims, Company I, 1st South Carolina Cavalry, was “present” with Hampton’s Brigade that clashed with Union cavalry at Gettysburg, attempting to disrupt the Union rear on what is now known as East Cavalry Battlefield. The 1st South Carolina Cavalry also served with honor at Fredericksburg and Brandy Station in Virginia.

Following Gettysburg, every family in the path of Union and Confederate armies was gripped in fear while their crops and livestock were destroyed. Land records in the Washington County Court House list farmers in the county who were forced to declare bankruptcy following the war. The Wolf farm felt the effects of civil war in 1862 and the next year during the Confederates' retreat in July from Gettysburg. A Wolf descendant noted, "Several times Civil War soldiers came to the farm, and my great-grandmother (Ann Maria Wolf) would always give them something to eat no matter what side they were on.”

The old homestead also had an abundance of another source alluring and essential to a cavalry unit: water. Horses needed an average of five gallons of water daily. Could it be while on a scouting mission, Private Sims left his canteen at the spring right beside Reverend Wolf’s home? Or perhaps Private Sims simply took a metal canteen from a dead Yankee and discarded his own.

Speculation will always surround how Daniel Wolf acquired Sims’ canteen, but there are several possibilities. After defeat at Gettysburg, Robert E. Lee depended on his cavalry to scout a safe passage for the Army of Northern Virginia back to Southern soil. On July 8, 1863, the 1st South Carolina (Wade Hampton’s Brigade) engaged Federal cavalry at Boonsboro, just east of Wolf’s farm. These same mounted troops were also present at Williamsport, Md., where the Rebel army crossed the swollen Potomac River, ending the Gettysburg campaign. Wolf’s land is situated between Boonsboro and Williamsport. So Reverend Wolf could have found the canteen at one of these locations or anywhere in between -– if not at the natural spring right beside his home.

Based on his military file, Richard Sims was employed as a clerk in his hometown of St. Paul’s Parish, Colleton County, S.C., just prior to the War Between the States. The small village is just southwest of Charleston, where the Civil War began April 12, 1861, with the Rebel shelling of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. An 1860 census for St. Paul’s Parish lists Richard Sims living with his parents, Edward L. and Sara Sims, along with an older sister, Elizabeth, and three younger brothers, John, James and Edward.

|

Back of 1st South Carolina cavalryman Richard Sims' canteen.

Note original spout. (Photo Richard E. Clem) |

When war looked as if it was going to last longer than expected, 23-year-old Richard Sims enlisted (April 3, 1862) at Parker’s Ferry, near St. Paul’s Parish. In June 1863, the 1st South Carolina Cavalry was transferred to Virginia, where it was assigned to General Wade Hampton’s Brigade, General J.E.B. Stuart’s Cavalry, Army of Northern Virginia. In all probability, Sims' canteen was left behind in Washington Country during the Rebels' retreat from the blood-stained fields of Gettysburg.

During his military career, Private Sims was listed as “company blacksmith,” according to Federal archives. For this back-breaking service, he was paid a dollar extra per month for shoeing horses.

A muster roll states he received “pay for use of horse from Oct. 31, 1863 to Nov. 28, 1863, at 40 cents per day.” Yes, the Confederacy paid their cavalrymen for service of their personal horses, but remember, the South had an abundance of “worthless” Confederate money.

The year 1864 was one of trials and testing for Richard Sims. On Jan. 8, he was admitted to Jackson Hospital in Richmond because of a chronic ulcer of left leg. This open, painful sore, perhaps caused by the shoeing of horses and days riding in the saddle, forced Sims to leave the cavalry. In the fall of 1864, the 1st South Carolina Cavalry was ordered south to defend its native state and surrounding area. Physically unfit for duty for almost a year, Sims was discharged from army headquarters on Dec. 10, 1864, at Pocotaligo, Ga. After the war, no record shows Richard Sims or his family living in St. Paul’s Parish. Perhaps he moved west like so many other Civil War veterans. Did he have a wife or children? Where is he buried? What did he look like? These questions will always be associated with the letters carved in the old canteen -- a name without a face.

It's not impossible Daniel Wolf may have personally met the Rebel horseman. Stated earlier, as company blacksmith, Sims could have stopped at Wolf’s spring to water his horse or to repair a damaged shoe of a comrade’s mount. He could have been one of those “Civil War soldiers” who was fed by Ann Maria Wolf. As of December 2016, the Confederate canteen was still well preserved in Washington County at the home of a great-great-grandson of Daniel Wolf.

The name “Richard Sims” will never grace a battlefield monument. But after more than 150 years, his well-preserved canteen of Confederate hardwood remains a silent symbol of a lost cause.

SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

--Brooks, U. R.,

Stories of the Confederacy, Columbia, S.C., The State Company, 1912.

--Davis, Burke,

Gray Fox, New York, Rinehart and Co., 1956.

--Henry, Maurice J.,

History of the Church of the Brethren, Brethren Publishing House, Elgin, Ill., 1936.

--McSwain, Eleanor D.,

Crumbling Defenses, or Memoirs and Reminiscences Of Colonel John Logan Black C.S.A., Macon, Ga., 1960.

--Williams, Thomas J. C.,

History of Washington County, Maryland, Hagerstown, Md., 1906.

--

Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Vol. III, New York, New York, Thomas Yoseloff, Reprint 1956

--National Archives, Military Service Records, Washington, D. C.

--

North South Trader’s Civil War, Vol. XVII, No. 2.

--

The Official Record of the Union and Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion

--South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, S.C.

--U.S. Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Carlisle, Pa.

The author owes gratitude to the following for their interest and invaluable contributions that made the story of Sims’ canteen possible:

Brent C. Brown, Sumter, S.C.

Margo W. Everett, Walterboro, S.C.

Louise Arnold-Friend, Carlisle, Pa.

Patrick McCawley, Columbia, S.C.

Glenn F. McConnell, Charleston, S.C.

Russell Thurmond, Sumter, S.C.

Kipp Valentine, Charleston, S.C.

Dave Williams, Hanover, Pa.