|

A fallen Confederate at Petersburg in 1864. (Thomas C. Roche | Library of Congress)

CLICK ON ALL IMAGES TO ENLARGE. |

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter

After the publication in 1886 of his eloquent, unvarnished account of service in the Army of the Potomac, Frank Wilkeson received reviews any author would crave.

"No book about the war for the Union can compare either style or in readableness ...," the

Philadelphia Times wrote about

Recollections of a Private Soldier in the Army of the Potomac. "Mr. Wilkeson's style is as crisp as a new treasury note. It is as clear as a trumpet-call. It is as deliciously breezy as a morning in May. It is impossible to take up his book and put it down without reading it."

|

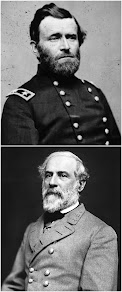

| Frank Wilkeson |

Noted the

Baltimore Sun: "Mr. Wilkeson occupies a rank as a writer which entitles his opinions to be weighed as those of a man of recognized ability, and his fearlessness in publishing them, when he knew they will be unpalatable to most of his readers and probably expose him to much

obloquy, serves respect."

"Everyone," another newspaper wrote, "will gain a prize by possession of this book."

A son of a well-known journalist,

Wilkeson enlisted at 16 in 1864 after running away from home. On July 1, 1863, his older brother,

Bayard, a lieutenant in the 4th United States Regular Artillery, suffered a mortal wound at Gettysburg. As a private in the 11th New York Light Artillery, Frank witnessed some of the worst fighting of the war — at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Courthouse, North Anna River, Cold Harbor and Petersburg. He somehow finagled his way onto the battlefield and fought as infantry at the Wilderness.

Wilkeson — who became a well-known journalist in his own right in the 1880s — wrote compelling chapters on the major Overland Campaign battles in

Recollections. But it's an 11-page chapter entitled

"How Men Die in Battle,

" as raw and ugly as a large, open wound, that captivates — and horrifies — me most. Here's the excerpt from Wilkeson's remarkable work:

|

| Famous "Harvest of Death" photo of Union dead at Gettysburg. (Alexander Gardner | Library of Congress) |

Almost every death on the battle-field is different. And the manner of the death depends on the wound and on the man, whether he is cowardly or brave, whether his vitality is large or small, whether he is a man of active imagination or is dull of intellect, whether he is of nervous or lymphatic temperament. I instance deaths and wounds that I saw in Grant's last campaign.

On the second day of the battle of the Wilderness, where I fought as an infantry soldier, I saw more men killed and wounded than I did before or after in the same time. I knew but few of the men in the regiment in whose ranks I stood; but I learned the Christian names of some of them. The man who stood next to me on my right was called Will. He was cool, brave, and intelligent. In the morning, when the Second Corps was advancing and driving Hill's soldiers slowly back, I was flurried. He noticed it, and steadied my nerves by saying, kindly: "Don't fire so fast. This fight will last all day. Don't hurry. Cover your man before you pull your trigger. Take it easy, my boy, take it easy, and your cartridges will last the longer." This man fought effectively.

During the day I had learned to look up to this excellent soldier, and lean on him. Toward evening, as we were being slowly driven back to the Brock Road by Longstreet's men, we made a stand. I was behind a tree firing, with my rifle barrel resting on the stub of a limb. Will was standing by my side, but in the open. He, with a groan, doubled up and dropped on the ground at my feet. He looked up at me. His face was pale. He gasped for breath a few times, and then said, faintly: "That ends me. I am shot through the bowels." I said: "Crawl to the rear. We are not far from the intrenchments along the Brock Road; I saw him sit up, and indistinctly saw him reach for his rifle, which had fallen from his hands as he fell. Again I spoke to him, urging him to go to the rear. He looked at me and said impatiently: "I tell you that I am as good as dead. There is no use in fooling with me. I shall stay here." Then he pitched forward dead, shot again and through the head. We fell back before Longstreet's soldiers and left Will lying in a windrow of dead men.

When we got into the Brock Road intrenchments, a man a few files to my left dropped dead, shot just above the right eye. He did not groan, or sigh, or make the slightest physical movement, except that his chest heaved a few times. The life went out of his face instantly, leaving it without a particle of expression. It was plastic, and, as the facial muscles contracted, it took many shapes. When this man's body became cold, and his face hardened, it was horribly distorted, as though he had suffered intensely. Any person, who had not seen him killed, would have said that he had endured supreme agony before death released him. A few minutes after he fell, another man, a little farther to the left, fell with apparently a precisely similar wound. He was straightened out and lived for over an hour. He did not speak. Simply lay on his back, and his broad chest rose and fell, slowly at first, and then faster and faster, and more and more feebly, until he was dead. And his face hardened, and it was almost terrifying in its painful distortion.

I have seen dead soldiers' faces which were wreathed in smiles, and heard their comrades say that they had died happy. I do not believe that the face of a dead soldier, lying on a battle-field, ever truthfully indicates the mental or physical anguish, or peacefulness of mind, which he suffered or enjoyed before his death. The face is plastic after death, and as the facial muscles cool and contract, they draw the face into many shapes. Sometimes the dead smile, again they stare with glassy eyes, and lolling tongues, and dreadfully distorted visages at you. It goes for nothing. One death was as painless as the other.

After Longstreet's soldiers had driven the Second Corps into their intrenchments along the Brock Road, a battle-exhausted infantryman stood behind a large oak tree. His back rested against it. He was very tired, and held his rifle loosely in his hand. The Confederates were directly in our front. This soldier was apparently in perfect safety. A solid shot from a Confederate gun struck the oak tree squarely about four feet from the ground; but it did not have sufficient force to tear through the tough wood. The soldier fell dead. There was not a scratch on him. He was killed by concussion.

While we were fighting savagely over these intrenchments the woods in our front caught fire, and I saw many of our wounded burned to death. Must they not have suffered horribly? I am not at all sure of that. The smoke rolled heavily and slowly before the fire. It enveloped the wounded, and I think that by far the larger portion of the men who were roasted were suffocated before the flames curled round them. The spectacle was courage-sapping and pitiful, and it appealed strongly to the imagination of the spectators; but I do not believe that the wounded soldiers, who were being burned, suffered greatly, if they suffered at all.

Wounded soldiers, it mattered not how slight the wounds, generally hastened away from the battle lines. A wound entitled a man to go to the rear and to a hospital. Of course there were many exceptions to this rule, as there would necessarily be in battles where from twenty thousand to thirty thousand men were wounded. I frequently saw slightly wounded men who were marching with their colors. I personally saw but two men wounded who continued to fight.

During the first day's fighting in the Wilderness I saw a youth of about twenty years skip and yell, stung by a bullet through the thigh. He turned to limp to the rear. After he had gone a few steps he stopped, then he kicked out his leg once or twice to see if it would work. Then he tore the clothing away from his leg so as to see the wound. He looked at it attentively for an instant, then kicked out his leg again, then turned and took his place in the ranks and resumed firing. There was considerable disorder in the line, and the soldiers moved to and fro-now a few feet to the right, now a few feet to the left. One of these movements brought me directly behind this wounded soldier.

|

| Skulls and bones inside Federal lines near Orange Plank Road in the Wilderness, (Library of Congress) |

I could see plainly from that position, and I pushed into the gaping line and began firing. In a minute or two the wounded soldier dropped his rifle, and, clasping his left arm, exclaimed: "I am hit again!" He sat down behind the battle ranks and tore off the sleeve of his shirt. The wound was very slight-not much more than skin deep. He tied his handkerchief around it, picked up his rifle, and took position alongside of me. I said: "You are fighting in bad luck to-day. You had better get away from here." He turned his head to answer me. His head jerked, he staggered, then fell, then regained his feet. A tiny fountain of blood and teeth and bone and bits of tongue burst out of his mouth. He had been shot through the jaws; the lower one was broken and hung down. I looked directly into his open mouth, which was ragged and bloody and tongueless. He cast his rifle furiously on the ground and staggered off.

The next day, just before Longstreet's soldiers made their first charge on the Second Corps, I heard the peculiar cry a stricken man utters as the bullet tears through his flesh. I turned my head, as I loaded my rifle, to see who was hit. I saw a bearded Irishman pull up his shirt. He had been wounded in the left side just below the floating ribs. His face was gray with fear. The wound looked as though it were mortal. He looked at it for an instant, then poked it gently with his index finger. He flushed redly, and smiled with satisfaction. He tucked his shirt into his trousers, and was fighting in the ranks again before I had capped my rifle. The ball had cut a groove in his skin only. The play of this Irishman's face was so expressive, his emotions changed so quickly, that I could not keep from laughing.

|

| Cropped enlargement of an image of a Union field hospital at Savage Station, Va. (Library of Congress) |

Near Spottsylvania I saw, as my battery was moving into action, a group of wounded men lying in the shade cast by some large oak trees. All of these men's faces were gray. They silently looked at us as we marched past them. One wounded man, a blond giant of about forty years, was smoking a short briar-wood pipe. He had a firm grip on the pipe-stem. I asked him what he was doing. "Having my last smoke, young fellow," he replied. His dauntless blue eyes met mine, and he bravely tried to smile. I saw that he was dying fast. Another of these wounded men was trying to read a letter. He was too weak to hold it, or maybe his sight was clouded. He thrust it unread into the breast pocket of his blouse, and lay back with a moan. This group of wounded men numbered fifteen or twenty. At the time, I thought that all of them were fatally wounded, and that there was no use in the surgeons wasting time on them, when men who could be saved were clamoring for their skillful attention.

None of these soldiers cried aloud, none called on wife, or mother, or father. They lay on the ground, pale-faced, and with set jaws, waiting for their end. They moaned and groaned as they suffered, but none of them flunked. When my battery returned from the front, five or six hours afterward, almost all of these men were dead. Long before the campaign was over I concluded that dying soldiers seldom called on those who were dearest to them, seldom conjured their Northern on Southern homes, until they became delirious. Then, when their minds wandered, and fluttered at the approach of freedom, they babbled of their homes. Some were boys again, and were fishing in Northern trout streams. Some were generals leading their men to victory. Some were with their wives and children. Some wandered over their family's homestead; but all, with rare exceptions, were delirious.

At the North Anna River, my battery being in action, an infantry soldier, one of our supports, who was lying face downward close behind the gun I served on, and in a place where he thought he was safe, was struck on the thighs by a large jagged piece of a shell. The wound made by this fragment of iron was as horrible as any I saw in the army. The flesh of both thighs was torn off, exposing the bones. The soldier bled to death in a few minutes, and before he died he conjured his Northern home, and murmured of his wife and children.

In the same battle, but on the south side of the river, a man who carried a rifle was passing between the guns and caissons of the battery. A solid shot, intended for us, struck him on the side. His entire bowels were torn out and slung in ribbons and shreds on the ground. He fell dead, but his arms and legs jerked convulsively a few times. It was a sickening spectacle. During this battle I saw a Union picket knocked down, probably by a rifle-ball striking his head and glancing from it. He lay as though dead. Presently he struggled to his feet, and with blood streaming from his head, he staggered aimlessly round and round in a circle, as sheep afflicted with grubs in the brain do. Instantly the Confederate sharp-shooters opened fire on him and speedily killed him as he circled.

Wounded soldiers almost always tore their clothing away from their wounds, so as to see them and to judge of their character. Many of them would smile and their faces would brighten as they realized that they were not hard hit, and that they could go home for a few months. Others would give a quick glance at their wounds and then shrink back as from a blow, and turn pale, as they realized the truth that they were mortally wounded. The enlisted men were exceedingly accurate judges of the probable result which would ensue from any wound they saw. They had seen hundreds of soldiers wounded, and they had noticed that certain wounds always resulted fatally. They knew when they were fatally wounded, and after the shock of discovery had passed, they generally braced themselves and died in a manly manner. It was seldom that an American or Irish volunteer flunked in the presence of death.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES

--

Helena (Mont.) Weekly Herald, Dec. 30, 1886.

--

Philadelphia Times, Dec. 19, 1886.

--

The Baltimore Sun, Dec. 23, 1886.