|

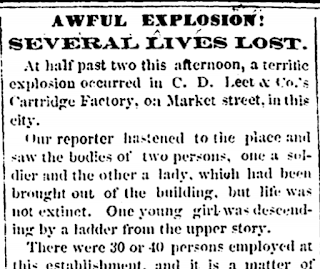

| A cropped enlargement of an 1862 lithograph shows the grim aftermath of the munitions factory explosion in Philadelphia. (Artist John L. Magee | Library Company of Philadelphia) |

Like this blog on Facebook | Watch my YouTube videos

At about 8:45 a.m. on March 29, 1862, neighbors of Professor Samuel Jackson's fireworks-turned-munitions factory heard a low rumble like the sound of distant thunder. Moments later came the roar of an explosion, followed by an even louder blast, as gunpowder and cartridges ignited in the south Philadelphia factory across the street from a prison.

'Human gore': More on deadly Civil War explosions on my blog

Many of the 78 factory workers, mostly women and girls, never had a chance to escape the conflagration unharmed. Eighteen employees died — including Jackson's own son, 23-year-old Edwin. Dozens of survivors suffered from burns or other injuries in the catastrophe — the Civil War's first munitions factory accident involving a major loss of life.

Like a scene from an Edgar Allan Poe horror story, dazed, burned and blackened survivors stumbled from the flaming and smoking ruins of the one-story building on Tenth Street. Others writhed in agony. "Their clothes all aflame," several female victims ran about "shrieking most pitifully."

Hundreds of curiosity-seekers rushed to the site, followed by firemen, who extinguished the blaze. Alerted by telegraph, the mayor soon arrived with the police chief. The city had not seen such an "intense state of excitement," the

Philadelphia Press reported, since a huge fire at the Race Street wharf in 1850.

"Frightful calamity," the

New York Herald called the disaster.

Frantic parents and friends of factory workers searched for loved ones among the crowd or in the ruins — "looking shudderingly," the

Philadelphia Inquirer reported, "among the fragments of clothing which still clung to the almost quivering remains of the mutilated dead." Rescuers commandeered several milk and farm wagons that happened by for use as ambulances. To keep gawkers at bay, police roped off the scene.

Some injured received care in nearby tenements, but most were sent to the city's Pennsylvania Hospital. Several even had bullet wounds from exploding cartridges. Covered with soot, a badly burned young survivor ended up at a segregated hospital's area for Black patients. "[I]t was some time," the

Inquirer reported, "before the mistake was discovered and rectified." He died the next day.

At least five of the victims were teens; one was 12. When the blast rocked the building, 14-year-old John Yeager was carrying a box of bullet cartridges that also exploded, knocking out his eyes. His sister, Sarah, also suffered injuries. They helped support a widowed mother.

Twenty-two-year-old Richard Hutson spent the last hours of his life at the house of Margaret Smith, who lived on Wharton Street, near the factory. His face was as "black as a man's hat" because of severe burns. "He seemed to be troubled with the idea that he had caused the mischief," recalled Smith, "but we tried to comfort him."

|

The Philadelphia Inquirer provided extensive

coverage of the disaster. |

Widows Margaret Brown and her sister, Mary Jane Curtin, suffered terribly. Five of Brown's children who worked in the factory suffered injuries. Blown across the street into a wall of

Moyamensing Prison by the blast, Mrs. Curtin — the superintendent of children at the factory — somehow escaped physical injury. But Mary Jane lost the $60 in gold she was carrying. Her three children, also munitions workers, suffered severe burns.

Rescuers found Edwin Jackson's body, "shockingly burned and multilated," among the charred factory ruins. He was overheard the previous evening saying he was unafraid of any explosion at his father's facility. Also employed in the factory, Samuel Jackson's daughters, 20-year-old Josephine and 18-year-old Selina, suffered severe burns.

Thankfully, heroes emerged to aid the sufferers: A woman cut her shawl in two, wrapping the pieces around two "half-naked" young girls, both factory workers. A court officer put his coat around a burning girl, putting out the flames and perhaps saving her life. And a Union cavalry officer, who happened to be riding past the factory, picked up a horribly burned victim and dropped him off at a drug store for medical aid. (When the soldier returned to his camp, he found a detached hand in his carriage.)

Do you know more about this Philadelphia disaster? Email me at jbankstx@comcast.net

But the catastrophe also brought out the worst in humankind: In the chaos, scoundrels snatched clothes from Mrs. Conrad's explosion-battered tenement on Austin Street, a block or so from the blast. A ragpicker offered fragments of clothes from the explosions for 25 cents. And when two victims sought aid at a residence in the neighborhood, the lady of the house indignantly slammed the door in the women's faces, telling them "she did not keep a house for working girls to enter." The local newspaper heaped scorn on the door-slammer: "Was the woman insane, or a fiend, or was it merely an instance of what utter vulgarity is capable of?"

Heard a great distance away, the explosions shattered windows, damaged shutters and sashes, blew doors off hinges, wrecked plaster and toppled furniture in nearby homes. The blast catapulted a man cleaning a lamp in front of a tavern headfirst through the building's doorway. He survived, but the lamp got "broken to atoms." Even inmates in gloomy

Moyamensing Prison — the castle-like structure nearby where Poe once slept off a bender — got rattled.

Grisly discoveries put an exclamation point on this Saturday horror show.

|

A 1901 photo of Moyamensing Prison. Mary Jane Curtin, superintendent of children at Jackson's factory,

was sent sailing into the prison wall by the blast. (Philadelphia Prison Society) |

|

| An illustration of the disaster in the Philadelphia Inquirer on March 31, 1862. |

Blood of the victims streaked the walls of houses in the neighborhood. A cheek from a victim's face stuck to a building on Tenth Street. A portion of a thigh plopped in a yard, near where it left a bloody mark on the rear brick wall of a tavern. A stomach landed atop a tenement building, A severed arm hit a woman in the head, knocking her down, and a scorched and fractured skull with gray hair landed in the street. It probably was from Yarnall Bailey, a 60ish factory worker from West Chester.

"Heads, legs and arms were hurled through the air, and in some instances were picked up hundreds of feet from the scene." the

Inquirer reported. "Portions of flesh, brains, limbs, entrails, etc. were found in the yards of houses, on roofs and in the adjacent streets." A policeman filled a barrel with human remains.

|

On April 7, 1862, the Philadelphia Inquirer

wrote of the death of another munitions

factory worker. |

"I picked up a bit of skull, with the hair adhering to it, more than a block (an eighth of a mile) from the place," a

Herald correspondent wrote, "and a whole human head, afterwards recognized as that of John Mehaffey, was found in an open lot against the prison wall."

In perhaps the ghastliest news from this awful day, a man told an

Inquirer reporter that he saw a boy going home with a human head in his basket. The lad said it was his father's.

Two days after the disaster, more than 2,000 people sought admission to Pennsylvania Hospital to check on the injured. "Such a rush to this institution," the

Press wrote, "was never before known."

GOOGLE STREET VIEW: Present-day view of long-gone munitions factory site.

Moyamensing Prison site at left; it's now site of a supermarket and a parking lot.

Authorities worked quickly to determine the cause of the explosions. The fire marshal convened a coroner's jury, whose gruesome tasks included examining remains of victims at the First Ward police station, some "blown literally to atoms." In the vest pocket of one of the victims, it found a note: "J.H. Mooney, No. 440 Walnut St. Brotherly Love Section."

The day after the explosions, the six-person jury also stopped at the home of Professor Jackson, who was not in his factory when the blasts occurred. The 45-year-old pyrotechnic wizard had to be strong this day: The jury examined his son's battered body in Jackson's Federal Street house before Edwin's burial in Odd Fellows Cemetery.

|

On April 3, 1862, the Philadelphia Inquirer

told readers about

funerals for victims of the explosions. |

After the war broke out, the U.S. government had contracted Jackson's fireworks factory to make millions of "Dr. Bartholow's solid water-proof patent cartridges," a "peculiarly made" ammunition for cavalry pistols.

"Innocent labors upon visions of beauty and delight have thus been diverted towards preparing necessary means for the destruction of demon-impelled men who have involved the country in war, from which it can only be rescued by their death or disperson," the

Inquirer wrote.

In the three weeks previous to the tragedy, Professor Jackson reportedly suffered from the strain to produce 1.5 million cartridges for the Army of the Potomac.

The factory, which made about 7,500 cartridges a day, consisted of frame structures and a brick structure about 10 x 12 feet. Boards covered the powder magazine — "merely a large hole dug in the ground," the

Press reported.

Workers stored about 50,000 cartridges in the factory moulding room, where eight men and four boys worked, and a finishing room, where women and girls placed bullets into cartridges. Fifty pounds of loose black powder and several kegs of the highly combustible material occupied other areas in the tight quarters.

|

Samuel Jackson's factory produced Bartholow's

cartridges for cavalry pistols. |

The day after the disaster, the fire marshal concluded the first explosion occurred in the moulding room, where the strike of a mallet may have caused the spark that set off a 30-second chain reaction of death and destruction. But he didn't know for sure — all the witnesses in that area were either dead or too badly injured to aid the investigation. Ultimately, the jury determined the detonation of a scale of dry powder caused the castastrophe.

"[M]any obviously essential precautions to prevent [the] accident," it concluded, "seemed to have been entirely neglected." But no one faced charges for the disaster.

Wrote the

Herald about the tragedy: "It is a solemn and terrible warning to those working in similar establishment, and we trust that its effect will be to make [munitions workers] more careful of their own safety by the strict observance of those cautions, the neglect of which may consign hundreds to untimely graves and carry suffering and desolations into many homes."

|

Well into June 1862, the Philadelphia Inquirer

reported, victims from the munitions factory

explosions remained hospitalized. |

Two weeks after the disaster, a concert was held in Philadelphia to aid explosion victims. Those who attended paid 25 cents for the event, which raised nearly $400.

Professor Jackson's factory eventually re-opened in nearby Chester, Pa., along the Delaware River. Jackson storied black powder for the operation on a boat offshore, a safe distance from the factory. Despite the deadly accident, the professor had no trouble filling his ranks with female workers, who earned the princely sum of 40 cents per thousand cartridges made.

"[T]hey would rather earn a living salary, at risk of their lives," the

Inquirer wrote in a sad commentary of the era, "than endure the indignities and hardships to many forms of female occupation."

POSTSCRIPT: Were any other lessons learned from the Philadelphia disaster? Perhaps not. On Sept. 17, 1862, 78 workers, mostly women, were killed in an explosion at the

Allegheny Arsenal near Pittsburgh. Within the next five months, dozens were killed in arsenal explosions in

Jackson, Miss., and

Richmond. And on June 17, 1864 — a brutally hot day in the U.S. capital —

21 women died in an explosion at the Washington Arsenal. Most of the victims were young, Irish immigrants. President Lincoln attended their mass funeral.

-- Have something to add, correct? E-mail me at jbankstx@comcast.net

SOURCES

—

Baltimore Sun, March 31, 1862

—

New York Herald, March 31, April 1, 1862

—

Philadelphia Inqurier, March 31, April 1, April 5, April 7, April 12, May 2, 1862

—

Philadelphia Press, March 31, 1862