|

| More than 16,000 Union soldiers were buried at Nashville National Cemetery. |

In fall 1866, the Nashville Union American reported, "a gang of negroes" began clearing the site Thomas suggested, and by late that year, the grounds were ready for the burial of Federal dead. "Some time will be required to complete this worthy undertaking," the local newspaper noted, "as there are about twenty thousand soldiers buried near this point, and some fifty or sixty per day will probably be average removals."

|

| Railroad tracks bisect Nashville National Cemetery. George Thomas would be pleased. |

If you can ignore the hum of traffic on busy Gallatin Pike, the 64-acre cemetery remains an oasis in what was countryside six miles or so north of downtown Nashville in the 19th century. From the bottom of a hill on the 64-acre grounds, the waves of gravestones seem overwhelming. Almost on cue during my visit, graffiti-scarred CSX cars rumbled by on train tracks that still bisect the cemetery. The Rock of Chickamauga" would be pleased.

Perhaps "Pap" Thomas would be pleased, too, that I paid respects Saturday to three Wisconsin soldiers. Here are snapshots of their lives:

|

| Edward Soper's gravestone in Nashville National Cemetery is in Section J, site 14605. |

"I called to see him the evening before we left [for Paducah, Ky.]," Captain John W. Moore wrote Soper's widow, Josepheen, "and I found him very bad but had no idea of it resulting so seriously and do asure you that the notice of his deth was very astonishing to me and do asure you that I simpathize with you. My hart akes for you." (See full transcript below.)

Besides Josepheen, Edward left behind two children: Charles, 4, and Flora, almost 5 months.

|

| (National Archives via fold3.com) |

Hed quarters, Co. "E." 44th Regt. Wis,. Infantry

Paducah, April 18, 1865

Mrs. Josepheen Soper

Dear Madam:

It is my painful duty to inform you that I have just received the sad intelligence of the deth of your husband Edward Soper. He died on the 9th Inst. Post Hospital Nashville, Tenn. We left him there when we left. He was on gard a few days before and in the night fell over a bank and shot his nee. I called to see him the evening before we left and I found him very bad but had no idea of it resulting so seriously and do asure you that the notice of his deth was very astonishing to me and do asure you that I simpathize with you . My hart ...

|

| (National Archives via fold3.com) |

I have the honor of subscribing my self yours very respectfully.

J.W. Moore

Capt. Co "E", 44th Regt. Wis. Infantry

Paducah Ky.

|

| Wilhelm Spickermann's gravestone is in Section D, site 3342. I placed a penny, Lincoln side up, atop his marker. (CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

Sadly, Wilhelm wasn't given a furlough when two of his three children died in Wisconsin while he was in the army. (The Spickermanns' lone surviving child, a girl named Minnie, was 2 in 1863.)

|

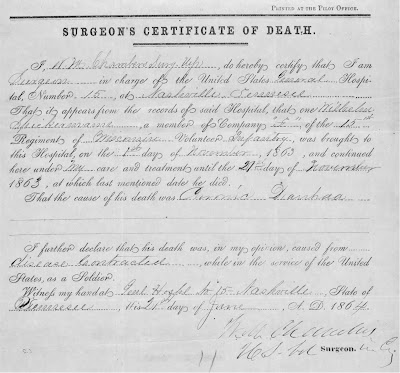

| Death certificate for Wilhelm Spickermann, who died from chronic diarrhea in Hospital No. 15 in Nashville on Nov. 21, 1863. (National Archives via fold3.com | CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE.) |

Spickermann's wife, Sophia, filed for a widow's pension, which was approved in 1864. Years later, things got really strange.

In 1878, Widow Spickermann was dropped from the pension rolls because her $8-a-month allotment had gone unclaimed for three years. In October 1892, the 60-year-old applied to restore it. An agent from the U.S. Pension Bureau sought her out for an interview to confirm her "widowhood." The intrepid special investigator was, ah, dubious about her request.

"From the evidence," he wrote, "it appears that claimant resided in Wisconsin till about 1867 when she went to New York City, and took up with a man named William Hoffman, 'kept house,' for him till 1872, when they left together to Stillwater, Minn., taking with them his boy and her girl, that she continued to keep house for Hoffman, and was known only as Mrs. Hoffman, from the time they landed in Stillwater until about 1883, when they left Stillwater and located at West St. Paul, Minn,, where she has kept house for him in an old tumble-down two-story frame tenement house."

Spickerman and Hoffman lived together in a poor section of St. Paul known as the Wagner Block, along the Mississippi River.

"These shanties are occupied by foreigners who are poverty-stricken and of questionable repute morally," the investigator wrote in his report, "and the neighborhood is anything but safe or inviting after dark. It was difficult for me to obtain testimony from these people as they were suspicious."

As for Hoffman, who immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1868, the agent was especially scathing. He arrived in America with a girl named Mary, "whom he had gotten in a family way," and she deserted him after the child was born. The couple were never married. "He is a libertine," the agent wrote of Hoffman, "and, while he was supporting claimant was running after women of ill-repute."

Hoffman's record for "truth and sobriety" were "bad," added the agent, whose moral outrage oozed from the pages of the widow's pension claim.

|

| Close-up of the gravestone for Wilhem Spickermann. |

Widow Spickermann's claim, the agent concluded, was of "very doubtful merit."

Sophia told a quite different story: When she moved to Stillwater, she made money sewing until her eyes got bad. Then she became the housekeeper for Hoffman, a laborer three or four years her junior whom she first met in New York. When the woman who Spickermann thought was Hoffman's invalid wife died, Sophia moved in with him in St. Paul. "It was while I was keeping house for Hoffman," she wrote "that I dropped my pension. I thought I had a living in my hands and did not want to bother about my pension." Besides, Hoffman's eldest son, Johnny, believed she was his mother. If she continued to draw the pension, Sophia said, Johnny could find out she was previously married and his feelings might be hurt.

Yikes, this one's a head-spinner.

As for all the talk that she was William Hoffman's wife, well, Spickermann insisted that was just rubbish. They never even slept in the same bed, Sophia claimed in a deposition, adding, "I have never had any sexual intercourse with William Hoffman at any time." Sophia said a miffed Hoffman sometimes even showed her the door, telling her, "I keep you long enough, go, and see how you get along." She said she also took care of Hoffman's teen-aged son, Henry, an aspiring baker, "as if he was my own son." He even called her "Ma."

William Hoffman, too, denied he was married to Spickerman, whom he insisted was merely his housekeeper. "If I marry," he said, "[his son's mother] may put me in state's prison." He said he only supplied Sophia with a place to live and clothes for Minnie. The investigator was highly skeptical. "Unreliable," he wrote next to Hoffman's name in his report.

Hoffman's Wagner Block neighbors offered conflicting stories. Some said he and Sophia lived as man and wife; others weren't so sure. "I don't know her name," one of them said, "but it ain't Hoffman."

Ultimately, the U.S. Pension Bureau rejected her pension request. Years later, the bureaucrats re-examined her claim when she was no longer living with Hoffman. But "a careful review of all the evidence on file," the agency wrote in 1898, "fails to show that injustice was done her."

Oh, Lord, what would Wilhelm think?

|

| George West, who died of disease, rests in Plot E, gravesite 778. |

|

| A note signed by government undertaker William Cornelius regarding the disposition of George West's remains. (National Archives via fold3.com) |

William Cornelius, a local undertaker contracted by the Union Army to bury Federal and Confederate dead, buried West in Grave No. 3567 in the Soldiers' Cemetery in Nashville, near Fort Negley. (My gawd, there could be thousands of more bodies still there.) After the war, the private's remains were re-buried in Nashville National Cemetery.

West was survived by his wife, Jane, and their two children -- a 1-year-son named Julius Elton and a daughter named Georgia Edith. She was born the day her father died.

-- Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES:

-- Nashville Union and American, Sept. 9, 1866, Dec. 14, 1866.

-- The (Nashville) Tennessean, April 14, 1867.

-- Widows' pension files for Edward Soper, Wilhelm Spickermann and George West, National Archives and Records Service via fold3.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment