|

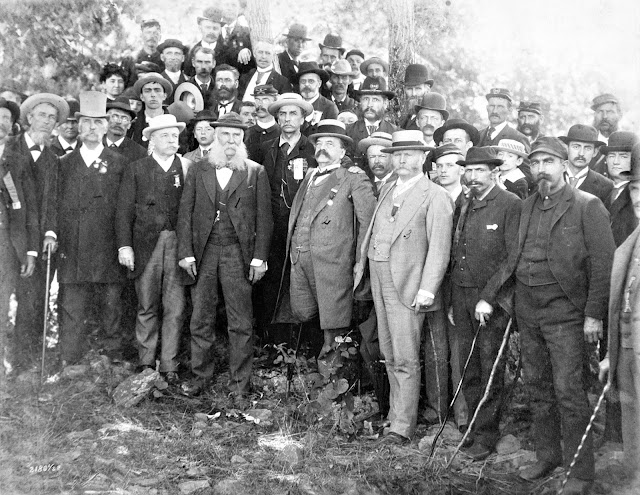

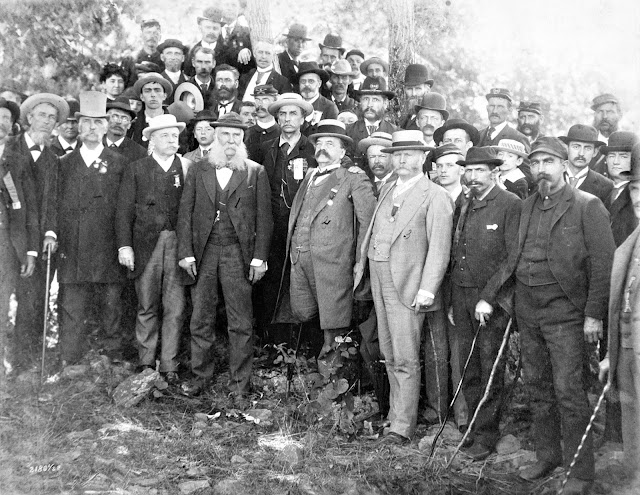

In an enlargement of the William Tipton image below, Civil War commanders (from left)

Joshua Chamberlain, Daniel Butterfield, James Longstreet and one-legged Dan Sickles pose in Gettysburg on July 3, 1888. Sickles lost his leg at Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. |

|

Longstreet and his former Union adversaries in Gettysburg at the 1888 reunion.

(CLICK ON IMAGES TO ENLARGE.) |

Like this blog on Facebook | Follow me on Twitter | My YouTube videos

A version of this feature story appeared in the January 2021 America's Civil War magazine.

For sheer star power, no gathering of Union and Confederate veterans rivaled the Grand Reunion at Gettysburg in 1888. "There are so many Generals and other chieftains here," a newspaper marveled, "that a catalogue of them would be as long as Homer's list of ships."

Former Army of the Potomac commanders Dan Sickles, Fitz-John Porter, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, Henry Slocum, Abner Doubleday and Francis Barlow, among other Union luminaries, joined ex-Army of Northern Virginia generals Wade Hampton, Fitzhugh Lee and John B. Gordon in Pennsylvania.

But the most celebrated man at the event sported massive, white whiskers and a cleanly shaven chin: James Longstreet, who commanded the Confederates’ First Corps at Gettysburg on July 1-3, 1863. Nearly everywhere Robert E. Lee’s “Old War Horse” went he drew appreciative, and often awestruck, crowds.

"No man now in Gettysburg," a New York newspaper wrote, “is more honored nor more sought than he."

For Longstreet, the visit to Gettysburg — his first since he commanded troops there — stirred a wide range of emotions: anxiety, joy, excitement, gratitude, pride and sadness. Here's how those remarkable days unfolded during the summer of 1888.

|

Veterans with family members at the dedication of the 121st Pennsylvania monument

at Gettysburg on July 4, 1888 -- one of many such gatherings in late June and early July

that year on the battlefield. (William Tipton photo | CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE.) |

‘The

sentiment which attracts … is powerful’

By 1888, James Longstreet proved more popular with Northerners than with White Southerners.

After the war, he aligned himself with Republicans, the party of Abraham Lincoln, and supported his friend and former military rival, Ulysses Grant, as president. “Ole Pete” also served in the Republican administration of President Rutherford Hayes, a Union veteran who missed fighting against Longstreet's soldiers at Antietam because of a wound suffered days earlier at South Mountain. Meanwhile, Longstreet received scathing rebukes from Lost Cause devotees for his criticism of Lee’s soldiering at Gettysburg and other perceived failings.

Longstreet, who lived in semi-retirement on his farm in Gainesville, Georgia, arrived in Pennsylvania on June 30. On the train ride to Gettysburg, he sat near Gen. Hiram Berdan, whose two regiments of sharpshooters slowed the Confederates’ advance at Devil’s Den and the Peach Orchard on the battle’s second day. The men eagerly discussed the fighting during their journey.

|

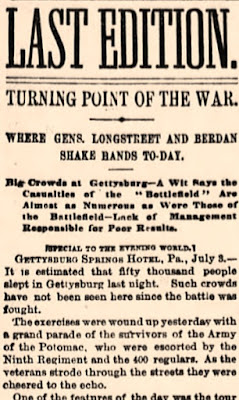

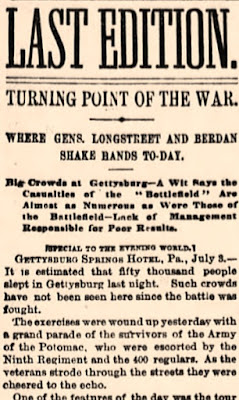

The press extensively covered

James Longstreet's visit to Gettysburg. |

The 67-year-old general, who stood about 6-foot-2 and weighed more than 200 pounds, looked “enfeebled,” according to the

New York Times. But another account called the broad-chested Longstreet “vigorous” despite his age.

In late June and the first days of July 1888, dozens of other trains packed with veterans unloaded at Gettysburg’s lone railroad depot for the Grand Reunion. “Most of the old soldiers went accompanied only by their memories,” according to an account, “but some took their wives and children with the intention of showing them the places in defense of which they fought so bravely.”

Rooms in the town's few hotels became scarce, so organizers erected tents for veterans on East Cemetery Hill and elsewhere. At least 30,000 people — White veterans and civilians alike — attended each day of the three-day event organized by the Society of the Army of the Potomac, a Union veterans’ organization. One newspaper estimated attendance as high as 70,000 for a single day.

“Such crowds,” the New York Evening World wrote, “have not been seen here since the battle was fought.” (Black veterans did not officially serve in the Army of the Potomac as soldiers in 1863, and thus few, if any, African Americans are believed to have attended.)

Unsurprisingly, the massive gathering — which included about 300 Confederate veterans — severely taxed resources in Gettysburg, population roughly 3,100. "The want of a head" in town, the Evening World reported, "has seriously interfered with the success of the reunion," while the New York Sun published a much more scathing Gettysburg critique:

“The town is indeed a poor place for the accommodation of such crowds of visitors as come here. There is not a really good hotel in the village. … Carriages are needed to go from point to point, for the battlefield covers an area of twenty-five miles, and the people take full advantage of the crowds and gouge everyone who hires a buggy or a hack. The extortion is worse than that practiced by the St. Louis hotel people during the Democratic Convention. And yet, in spite of all these unpleasant things, the people come, for the sentiment which attracts is more powerful than the feeling of disgust created at the meanness of the people of the place."

Despite less-than-ideal conditions, veterans — most in their early 50s — eagerly re-connected with former comrades. “The meeting of the survivors of the armies of Meade and Lee on the field of Gettysburg,” a Pennsylvania newspaper proclaimed, “is the greatest occasion of the kind known in our history, if not in the annals of nations.”

Many veterans went souvenir-hunting for battle relics in fields and woodlots. Scores attended the dedication of more than two dozen battlefield monuments. At one of those events, a New Jersey veteran claimed he found in a rock crevice the cartridge box he had hidden during a retreat in July 1863. Two bullets remained in the bent and rusty relic, which he proudly took home.

|

An 1880s view of Spangler's Spring, where some

veterans partied at 1888 reunion. (William Tipton)

|

On East Cemetery Hill, four veterans of the Louisiana Tigers Brigade from New Orleans became the center of attention on ground where they made a desperate attack 25 years earlier. Pennsylvania veterans eagerly greeted the men, who wore blue, silk badges adorned with the letters “A.N.V.” for Army of Northern Virginia.

“[S]uch a shaking of hands,” the New York Times reported, “was never before seen on East Cemetery Hill.”

In town, residents and others hawked everything from lemonade and badges to horse-and-buggy rides, available for from 50 cents to $2.50 an hour. At the Catholic church in Gettysburg, Irish Brigade veterans attended a special mass for the fallen in battle. Meanwhile, attendees enjoyed bands that played “Marching Through Georgia,” “John Brown’s Body” and “The Star-Spangled Banner." At night, electric lights mounted on a tall mast lit up Cemetery Hill, creating a dazzling scene.

Many found time for carousing, too. At Spangler’s Spring, near Culp’s Hill, veterans partied hard after the reunion’s official end, drinking beer in “huge quantities.”

Cordiality among the former enemies largely took precedence, although Union men groused that some Confederate veterans wore lapel pins adorned with a Rebel flag. “That was the flag of treason and rebellion in 1861,” Union Gen. John Gobin

said in a speech, “and it is the flag of treason and rebellion in 1888.”

|

In a cropped enlargement of the William Tipton image below, Longstreet stands next to

former Union general Henry W. Slocum. Who else do you recognize? |

|

U.S. Army veterans and Longstreet on July 3, 1888. Dan Sickles, who lost a leg at Gettysburg,

stands next to Longstreet (right). (CLICK ON IMAGE TO ENLARGE.) |

‘Old

Pete’ and Sickles: ‘Friends in a moment’

Almost from the beginning, James Longstreet’s Gettysburg visit proved eventful and often surreal.

When word spread June 30 of Longstreet staying at the popular Springs Hotel, about two miles from town, hundreds headed in that direction. But the general had already left for the dedication of Wisconsin Iron Brigade monuments in Herbst's Woods. There, “Old Pete” briefly met with Rufus Dawes, the Iron Brigade officer whose soldiers captured 200 Confederates nearby in the unfinished railroad cut west of town on July 1, 1863.

“General,” Dawes said as he surveyed the area near the Chambersburg Pike, “it looks very different from the scene of 25 years ago.”

“Yes,” Longstreet said, “it reminds me of a camp meeting.”

Another U.S. Army veteran remarked to Longstreet that the battle might have ended quite differently had Confederate command listened to his advice. Then an attendee quizzed the general about Pickett’s Charge.

Were you really against it? the man wondered.

“Yes, sah,” Longstreet replied.

Asked if former Confederate Gen. Jubal Early — a high priest of the Lost Cause and a sharp critic of Longstreet — might attend the Grand Reunion, the general expressed his doubts. After all, the commander who ordered the sacking of nearby Chambersburg in 1864 probably would not have been well received on Pennsylvania soil.

Longstreet, though, rarely had a free moment at the reunion. Veterans of all stripes eagerly exchanged pleasantries and shook the hand of “Old Pete.”

Later that day, Longstreet dined at his hotel with 68-year-old Daniel Sickles — the first meeting of the former enemies. As commander of the Third Corps at Gettysburg, the controversial Sickles lost his right leg to enemy artillery on the battle’s second day.

“They were friends in a moment,” according to an account of their meeting, “and there was very little eaten at that table for 30 minutes as they talked about events a quarter century old.” While the old foes conversed, others in the room gawked and "let their dinner go almost untouched."

|

40th New York veterans and two women in Devil's Den pose for a photo at a reunion

in Gettysburg, perhaps in 1888. (William Tipton | Library of Congress) |

‘Something beyond description’

The pairing of Sickles, a cigar-smoking New Yorker, and Longstreet, a South Carolina-born part-time farmer, proved a hit. As a group of New York veterans marched through Gettysburg one morning, the two rode in a carriage behind them.

"This was a meeting of blue and gray worth recording," a Philadelphia newspaper correspondent wrote, "and as they passed along the street that led to Seminary Hill and Seminary Ridge the enthusiasm of the crowd who recognized them was something beyond description."

With Sickles and other former Union bigwigs, Longstreet visited the notable battlefield sites — the Peach Orchard, Wheatfield, Devil's Den and Little Round Top, the “apple of Longstreet’s eye.” Little had changed, the general observed, since his soldiers' desperate assaults on the Round Tops on July 2, 1863, and, a day later, at the "Bloody Angle" during Pickett's Charge. While he toured the battlefield, Longstreet called the charge "a great mistake" and discussed strategy and tactics with former Union commanders.

When the general began a tour on horseback with former U.S. Army generals Daniel Butterfield, Berdan, and others, a large crowd gave the group three cheers. After they reached the summit of Little Round Top, word quickly traveled of Longstreet's presence. Union veterans gathered nearby for a monument dedication rushed toward their former adversary.

"Boys, here's Longstreet!" shouted the one-legged Sickles as he sat at the foot of a tree, "and he meets us once more on Round Top." Three rousing cheers from the crowd of about 100 "went surging through the shimmering air to the plain below."

On July 1, Longstreet nearly broke down during a speech before an estimated 10,000 First Corps veterans in Reynolds Grove, near the monument to Union Gen. John Reynolds, who was killed on the first day of the battle.

As he walked to the massive speakers' stand, Longstreet received a loud Rebel yell greeting, the Gettysburg Cornet Band played "Dixie" and veterans crowded around the commander. "General,” a one-legged Federal veteran told Longstreet, “I fought against you at Round Top. I lost a wing there, but I am proud to meet you here."

“Yes,” Longstreet replied as he grasped the man’s hand, “those were hot times then. But I’m all right now.”

After Longstreet took his place on the stand, a former Federal officer shouted, "Comrades, you see on this platform one of the hardest hitters whoever fought against us. I propose we give three times three for General Longstreet, one of the best Union men now in the country!"

The crowd erupted, surging toward the wooden stand and "showering God bless you's” on the teary-eyed general.

Moments later, though, the platform collapsed amid shrieks, falling two feet, but no one suffered a serious injury. Smiling, Longstreet bowed left and right. Then “Old Pete,” his voice shaking as he began his speech, told the veterans of his pride in commemorating the battle and of his eagnerness “to mingle with those brave men who know how to appreciate heroism which will give up life for country's sake."

During his speech, Longstreet called the third day at Gettysburg the greatest battle ever fought.

“But times have changed,” he said, according to the Times. “Twenty-five years have softened the usages of war. Those frowning heights have given over their savage tone, and our meetings for the exchange of blows and broken bones are left for more congenial days, for friendly greetings, and for covenants tranquil repose.

"The ladies are here to grace the serene occasion and quicken the sentiment that draws us nearer together,” he continued. “God bless them and help that they may dispel the delusions that come between the people and make the land as blithe as bride at the coming of the bridegroom.”

|

| Longstreet appears in a cropped enlargement of the William Tipton image below. |

|

In July 1888, Longstreet posed on horseback with Daniel Butterfield (on second horse from right),

George Meade's former chief of staff, near the summit of Little Round Top. The

155th Pennsylvania monument appears in right background. BELOW: A present-day view.

|

'All were inspiring'

On July 2 at the national cemetery, the final resting place for more than 3,500 Federal soldiers, Longstreet shared the speaker’s rostrum with Sickles, Gordon, Barlow and other notables. Nearly 5,000 people crowded onto the hallowed ground where Abraham Lincoln had delivered the Gettysburg Address in November 1863. A New York Times reporter wrote about the remarkable scene:

"The actors were the very men who defended the ridge on whose slopes the cemetery lies against the repeated assaults led by the very men 25 years ago this very day who joined them here now in pledges of friendship, loyalty to a common flag and unity of devotion to a common country. All — place, scene, and the living figures of the men themselves — were inspiring."

|

A post-war photo of John Gordon,

who gave a speech at the

Gettysburg National Cemetery

at the 1888 reunion.

(The Cyclopaedia of American

biography) |

Shortly after 5 p.m., Sickles gave a short speech.

“As Americans,” said the general, who became instrumental in preserving the battleground, “we may all claim a common share in the glories of this battlefield, memorable for so many brilliant feats of arms.” He later read a telegram from Pickett’s sickly widow, who offered “God’s blessing” to the throng.

When Georgia governor John B. Gordon, a brigade commander at Gettysburg, received his introduction, a deafening roar greeted him.

“Hurrah!” and “Good!” the crowd shouted.

Longstreet spoke only a few sentences.

“I changed my suit of gray for a suit of blue so many years ago,” he said, further endearing himself to the Union vets, “that I have grown myself in my reconstructed suit of blue.”

At the dedication of the 95th Pennsylvania monument that day in the Wheatfield, though, the general’s actions spoke much louder than any words. Longstreet held the regiment’s tattered battle flag, pierced by 81 holes in fighting at Gettysburg, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Malvern Hill and elsewhere.

Gently, James Longstreet pressed the flag to his lips … and wept.

Have something to add (or correct) in this post? E-mail me here.

SOURCES- Harrisburg (Pa.) Independent, July 2, 1888

- Harrisburg (Pa.) Telegraph, July 5, 1888

- New York Evening World, July 3, 1888

- New York Sun, July 1, 1888

- New York Times, July 2 and 3, 1888

- New York Tribune, July 4, 1888

- Philadelphia Inquirer, July 3, 1888

- Philadelphia Times, July 3 and 5, 1888

- The Times Picayune (New Orleans), July 3, 9 and 13, 1888

Fantastic and Thanks

ReplyDeleteExcellent post John. It must have been an emotional occasion!

ReplyDeleteThanks, John. This one was fun. Pounded it out at Starbucks. Newspapers.com is amazing resource.

DeleteThank you John for writing this. It's always nice to learn more about your ancestry.

DeleteMy ancestors fought for the Confederacy and I’m so proud of them.

DeleteWell written and well done sir!

ReplyDeleteI bet it would have been something to have been there with those men.

Very interesting and well-written. And the sight of Longstreet with that peculiar beard is remarkable. Also: Was this the same period when lawsuits were being brought as to which state could claim a specific site on the battlefield based on the valor displayed on that particular site by its volunteers?

ReplyDeleteVery interesting and well-written. And the sight of Longstreet with that peculiar beard is remarkable. Also: Was this the same period when lawsuits were being brought as to which state could claim a specific site on the battlefield based on the valor displayed on that particular site by its volunteers?

ReplyDeleteI was just at Gettysburg a couple of days ago and, although I've been there many times, it never loses its charm as the premier Civil War battlefield. Stories like this continue to make it come to life. I looked at the Longstreet monument in a new light, appreciating him more, and seeing him also as the old "War Horse" visiting the battleground as an aging veteran, with a tear and twinkle in his eyes (and mine too).

ReplyDeletewonderful article, covering the feeling and emotion of these men returning to the location that probably produced more than one nightmare for anyone of them. Inspiring story of grace and dignity.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your work here. Interesting and moving. Pictures great,too. Thanks again for yet another note honoring our heritage.

ReplyDeleteGeneral Hood!

DeleteMy GG Grandfather fought and was killed at Crampton’s Gap , prior to Antitum for the South .

DeleteAntietam

DeleteJohn, thank you for telling the story of the 1888 Gettysburg reunion. Very moving. Surely a very emotional visit for those guys. Really enjoyed the piece on Mrs Longstreet as well. Incredible that fine lady was with us up until the 1960s!

ReplyDeleteAn extremely interesting article; thanks for contributing it.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting and great pictures. Thank you so much for posting, I'll be looking forward to many more !!

ReplyDeleteThis was amazing to read and the pictures put the cherry on top!! Thank you

ReplyDeleteKudos, John. Great article! I've never seen these pics before nor was I familiar with the aspects of the 1888 reunion you've shared. Thanks for your fine work.

ReplyDeleteLoved this, Thank You

ReplyDeleteWe'll done, great post

ReplyDeleteAwesome post. Funny how personalities never change, Longstreet and Chamberlain classy and true; Sickies, the man who damn near lost the battle disobeying orders looking like a 'Conquering hero', and Slocum who failed to support the Union troops west of Gettysburg on day 1 ( well at least he doesn't look so self important as the politico- general, Sickles. His wounding was bad for the CRA but good for the Union.

ReplyDeleteExcellent! Well written!

ReplyDeleteI'll never forget the first time I crossed that battlefield the hair on the back of my neck stood straight out

ReplyDeleteThanks for a great read John. From what I've read Longstreet may not have been so welcome in the some part of South at that time, no? I think he was one of the few ex-Confederate generals who became a Republican.

ReplyDeleteMy how times have changed...mutual respect for northerners and southerners...monuments understood. Bravery and patriotism not questioned. Truth was indisputable! Longstreet was a “war horse!”

ReplyDeleteThank you for the article,I love the remember or history and men and women that were part of it. Trying to put self in their place on how they felt and their beliefs. I’ve done my ancestry and found few Civil war vets. And a lot of direct a Revolutionary vets 3 of which fought for British. Thank you for walk thru history

ReplyDeleteThanks for telling the truth about our history!!

ReplyDeleteas a soldier I can understand the emotions I can not understand people that want to erase the south the confederate statues and the southern way of life. thru out history you will find warrior of both sides who respect each other. it appears the nation is more divided today then durning this time frame. thank you great article

ReplyDeletehttps://goaltwo.blogspot.com/2012/01/battle-of-football-evermore.html

ReplyDeleteThis is wonderful!!! Thank you for sharing!!!

ReplyDeleteExcellent post, great to read if thus event

ReplyDeleteAfter watching the movie “Gettysburg “ and doing some reading on Gen.Longstreet, I felt sorry for the general. Knowing that the charge wasn’t going to work,and then seeing all those men make the ultimate sacrifice,and then being blamed for what happened....

ReplyDeleteI visited Gettysburg for the first time a few weeks ago and am now watching the film. The charge seems senseless to me. What a burden for Longstreet but to refuse would probably have meant the end of his career. I'm glad he received honors throughout his later life. I'm sorry for those whose duty it was to participate in the charge.

DeleteThank you for a well written article for a legend! - General Longstreet! Huzzah!

ReplyDeleteWow! Great piece! This is one of the best accounts of the 1888 reunion that I have read, I think you captured the emotion of Longstreet’s visit quite well. I find it interesting that on his way home he would survive a substantial train wreck at the Fat Nancy trestle. Longstreet was one tough old bird.

ReplyDeleteThanks for an inspiring article Mr. Banks , People were definitely more Respectful of History back then. Learning from & not erasing history is the way of mending division , no matter what the Battle.

ReplyDeleteMuch appreciated!!

ReplyDeleteAwesome. Thank you!

ReplyDelete