|

| Brian Downey, creator of Antietam on the Web, on the 44-acre plot on the battlefield recently purchased by the Save Historic Antietam Foundation and Civil War Trust. (Photo courtesy Brian Downey) |

By the late 1980s, Brian Downey had collected so much information about the Battle of Antietam that he needed an outlet for his obsession. So when Al Gore's creation finally took off in the 1990s, Downey launched Antietam on the Web, now easily the deepest site on the Internet on the great battle.

Just skimming AoTW you'll find a lot to like -- an overview of the fighting, a blog, official reports, a Medals of Honor list and much more. Dive deeper and it gets crazy-good: Check out this PDF of the dead of the Maryland Campaign, updated through January 2018, and a map of historical tablets on the battlefield. There's plenty on the site to satisfy the newbie as well as the nerd.

By far my favorite AoTW feature -- and Downey's, too -- is a searchable list of battle participants, now up to more than 15,000. Some of the bios on the Antietam Roster include an image of the soldier, and many provide breadcrumbs in the form of links or other info for those who seek more depth.

|

| Home page of Antietam on the Web, recently redesigned by Brian Downey. |

"I think this is why I focus now on the people of 1862. I’m fascinated with their faces – trying to glimpse something of them as they were – and with learning a little about their lives. I can’t claim any deep knowledge, and this certainly is not exhaustive research, but I get a little closer to some of these men and that cataclysmic war every day."

Now retired and living in Florida, Downey served in the late 1970s and early '80s in the Navy aboard a vessel in the Western Pacific engaged in electronic warfare. "Thankfully," the 60-year-old told me, "no one ever shot at me." Later, Downey worked as a consultant to Navy offices in Washington D.C. He learned about databases and systems development -- skills that came in handy developing AoTW -- and was project manager on many contract software projects for civilian government agencies.

In a Q&A with the blog, Downey dishes on George McClellan, the number of hours he has devoted to his obsession, his favorite spot at Antietam ... and whether he has plans to develop another AoTW-like site about a certain Pennsylvania battle. (You may be surprised.)

|

| Downey's fascination with Antietam began with this photo of the bodies of Louisianans along Hagerstown Pike. (Alexander Gardner | Library of Congress) |

A simple question: Why did you start the site?

Downey: As a kid I was first fascinated by Antietam when I saw Alexander Gardner's horrifying battlefield photographs. In particular, the scene of dead Louisianans along the Hagerstown Pike. A large copy of that picture lived on my bedroom wall for years. In my teens, I read quite a bit about the War and Antietam. In my 20s, after several battlefield visits with my Dad, I started gathering more detailed information about the military units and their officers. Pretty soon I had file folders of notes and pieces of maps and bits of text. By the late 1980s, I was overwhelmed, and needed a way to make it all fit together. When the web and hypertext link technology came along in the 90s, I saw the tools I needed to make sense of it all. I've been somewhat obsessively collecting and correlating information about the battle in digital form on the web site ever since.

The site is deep and layered, with soldier profiles, after-action reports and much, much more. How much time do you figure you have invested in this?

Downey: I wish now I'd kept a log! In some years I put in more than others, trying to balance this obsessive behavior with family and work responsibilities. Say 10 hours a week or 500 a year. A few years quite a bit more, but that's probably a good average. Maybe 10,000 hours or five person-years altogether. Wow. I've not done the math before. Now that I'm retired I'm putting in more time; I'm afraid this is only going to get worse.

Most of my effort for the site goes into finding the soldiers, researching at least the basics for them individually, hunting photographs, and getting it all into the database. I spend from 10 minutes to two hours on each person. I suppose I could move faster and just crank on lists of names, but that wouldn't be nearly as much fun. I'm up to something over 15,000 people now, but I'll obviously never get to all of them, so I just keep on keeping on.

|

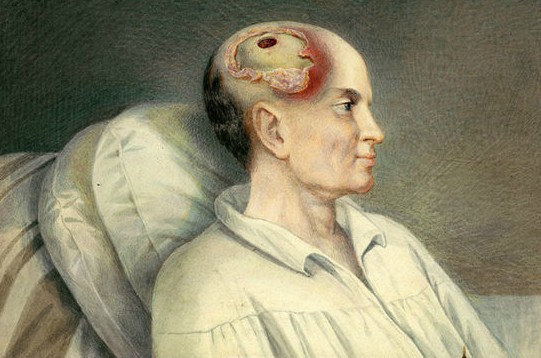

| 1863 lithograph of 4th New York Private Patrick Hughes, seriously wounded at Antietam. (Collection National Museum of Health and Medicine) |

Downey: As the cliche goes, there are as many stories as soldiers. I come upon good stories almost every day, but most of them are necessarily buried in the mass that is the AotW database. There's no easy way to remedy that, except as I occasionally pop out of research mode and feature a particularly interesting person on the blog or (more recently) on the AotW Facebook page.

One soldier in particular who stands out in my memory, mostly because of the gruesome wound he survived and the available contemporary images of it, was Private Patrick Hughes, 4th New York Volunteers. He and his mates in Company K experienced their first combat when they hit the Sunken Road at Antietam on that Wednesday morning. Patrick was shot through the head and initially got little medical treatment, probably because he was expected to die. But he survived and went on to a fairly normal life after the war. In 1870 his doctor said of him:

His memory is quite good, but by no means so good as before the injury. He is rather easily bothered and confused, and more irritable than formerly. The sight of his right eye, he thinks, is poor. Whisky affects him as usual. Sexual power undiminished. He has no paralysis. The wound of entrance is marked by a slight depression in the bone, the wound of exit by a hollow two and a half by two inches, and one inch deep. No bone has closed this opening, but the scalp and hair dip down into the hollow.

|

| Thomas Cartwright Jr. (NY State Military Museum) |

A more recent find: 41-year-old Lieutenant Thomas W. Cartwright of the 63rd New York Infantry, Irish Brigade. I was looking at him yesterday after seeing his name on a hospital list. He was slightly wounded at Antietam, was promoted to Captain of Company D in October, and escaped unhurt from combat at Fredericksburg in December, yet he resigned his commission in February 1863. Now I think I know why.

His 20-year-old son, Thomas Jr., was a Captain in the 5th New York, but was not at Antietam. He had been wounded at Gaines Mill in June. He died at Ebbitt House, Washington, D.C., on the day after Christmas 1862 from the effect of his wounds. I think this crushed his father, who could not continue in uniform. A tiny incident in the big scheme of things, but one of so many that made the war the horror it was.

As someone who’s crafted a web site or two, I am interested if you have any horror stories to tell – a code breakdown or somesuch perhaps?

Downey: Well, no horror stories, but a couple of times in the last decade I've had to rewrite obsolete code on the site, which was difficult, but not fatal. Software doesn't sit still, for obvious reasons of security and feature creep, so old code tends to go stale. Now in my professional career there were some tough patches, but I'd rather not revisit those, thank you. Nothing like that on AotW. I don't think I can credit my personal programming skill, though. The website is of fairly simple design with a robust database behind it. Not much to go wrong at this point.

What can we expect to see in the future on the site?

Downey: I'll concentrate on adding people to the database whenever I can. I'm overdue on a few of the Campaign maps too, though I don't feel those are high priority. I've recently redesigned the site and re-written much of the PHP code, so shouldn't need to do that again for a while.

As to features, I'm thinking about providing an API (application programming interface) for other enthusiasts to get at the AotW content directly from their own applications, if there would be any demand for that, but that's about it for now.

I do have a long-term worry, though. I have no immediate plans to stop, but I'm guessing I won't still be doing this in another 22 years. So what happens to the web site then? No one in my family is as excited by the subject as I am, so no inheritors there. I'd hate for it to just go dark. I'd like to think that at the least the soldier database -- the Antietam Roster -- will live on after me.

Something for me to think about.

What’s your favorite read about Antietam, and why?

|

| Sears' book on Antietam is an "excellent overview," Downey notes, but "not terribly objective" because the author "has his knives out for George McClellan." |

My favorite storyteller on the battle is Stephen Sears -- his Landscape Turned Red reads like a good suspense novel. Which it kind of is. Sears' style makes it easy to picture the complex activity of the Campaign, and he provides strong characters with a thrilling plot line. However, it's not terribly objective history, given that he has his knives out for George McClellan at the very start and drives his narrative to fit.

When asked for a book recommendation for someone who is just starting to learn about Antietam, I give Sears. With that caveat. It's an excellent overview and introduction.

I read non-fiction rather than fiction for fun, so that probably explains my other choice: Ezra Carman's Maryland Campaign of 1862 (manuscript). There are two editions out, by Jake Pierro and Tom Clemens. I really love Tom Clemens' excellent notes, so I use his volumes most. There's nothing like Carman, which is built in part on testimony from the veterans, for immense detail on the battle. I've read him through once and probably won't again -- it's not a breezy read -- but it is a go-to reference.

Everyone has a favorite spot on the Antietam battlefield. What’s yours, and why?

Downey: I've been on the battlefield many times, but I still get the chills every time. There are a number of spots where that happens for me: crossing the Nicodemus Farm toward the Bloody Lane, and walking in the West Woods around the Dunker Church, for example. But my favorite, most sacred, spot is just north of the Miller Cornfield, particularly at first light on a misty September morning. That was a kind of hanging or focal point - just before the battle opened and hell was unleashed -- and I can almost feel the massive weight of it when I'm there.

As you know, the Park Rangers do a spectacular job of interpreting that place and time each year on the Anniversary. A not-to-be-missed event for the early riser.

True or false: George McClellan was a good general.

Downey: That's a trick question. There's no right answer. Everyone who has studied the battle even a little bit seems to have a strong opinion on him.

If I judge McClellan against what he and his boss saw as his job in September 1862, I can credit him with doing what he was supposed to do: he got a badly disorganized Army together quickly, chased Lee down in Maryland, all while covering Washington, and stopped the threat, pushing the enemy back into Virginia.

|

| George McClellan (Library of Congress) |

As to the what-ifs surrounding George McClellan and the Maryland Campaign?

McClellan wanted to restore the Union as it had been, hoping to do it with limited war. He wasn't going for the jugular. By September 1862, of course, his President knew it was too late for that. And in hindsight, so do we. Most military minds would say that any general's real mission (which he never took on) is to destroy the enemy. And there were notable opportunities for some of that in September 1862. It's notoriously difficult to destroy an army, but it is likely that a more aggressive approach would have yielded better results.

So yes, like many -- including some of his soldiers-- I am disappointed by what McClellan didn't do. But that's speculation, not history. And that's as close as I can get to whether he was a good general or not.

And, finally, if someone came to you and said we want you to do a similar site on Gettysburg, what would you tell them?

Downey: I might run, screaming.

I understand its importance, but don't have the same passion or obsession for Gettysburg -- that "other battle" up North. Thank goodness no one is asking, though, so I don't have to worry about that.